Perceptual systems

Perceptual systems are designed to solve problems that arise in the activity of the subject; they constantly require perception, including sensory processes, to adequately reflect the situation. Depending on the nature of the perceptual tasks, reflection also turns out to be different, although the anatomical links of the sensory system - the receptors - remain unchanged. Indeed, in some cases, an accurate assessment of the spatial position of an object may be of particular importance, in others - the perception of the properties of its surface or shape. As a rule, within the framework of the same modality it is possible to solve a whole hierarchy of perceptual tasks.

In this regard, the position expressed by N.A. Bernstein is of great theoretical importance that, depending on the complexity of the movement, all types of afferentation, to a greater or lesser extent, take part in sensory corrections, performing the function of proprioception in the broad sense of the word. The complexity or level of a motor task determines the composition of sensory corrections with the help of which it can be solved.

These ideas were developed in detail by N.A. Bernstein in the theory of levels of movement regulation.

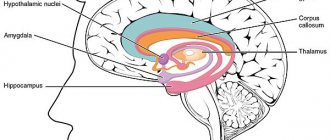

The first level of movement regulation is called the level of paleokinetic regulation. With its help, the simplest, purely reflexive movements are carried out, such as the knee reflex or vibrato of a violinist. The sensory link of this reflex ring is the muscular-strength components of proprioception, which are closed in the spinal cord and brain stem. Movements of the second most complex level of synergies require sensory corrections from the joint-spatial components of proprioception and contact exteroception. Synergies are stereotyped movements that involve large muscle groups. Examples of synergy would be most gymnastic exercises or smiling. The central regulation of movements at this level is carried out by the subcortical nuclei of the thalamus and pallidum. To perform movements at the next level in the hierarchy of the spatial field, vestibular afferentation, touch, vision and hearing are necessary. These are movements adapted to external space, such as throwing a ball or typing on a typewriter. The spatial field level is the first cortical level. Its neurological substrate is the basal ganglia and projection zones of various analyzers. Much more complex movements are performed at the level of objective action. The main regulator of movement in this case is the object itself: it is built in accordance with the logic of its use. At this level, weapon actions become possible. Neurophysiological mechanisms for the regulation of objective actions are located in the premotor and inferior parietal zones of the cerebral cortex. Even higher are the difficult-to-differentiate levels of higher symbolic coordination, such as speech and writing. Purposeful human movements are high-level movements.

The lower levels play a subordinate role in this case, performing background coordination.

The correctness of the idea that not only proprioception, but also exteroception is involved in the regulation of movements, is confirmed by a number of recently obtained data.

It is well known that speech articulations are controlled by proprioception from the vocal cords and larynx. At the same time, there is an unambiguous connection between a person’s articulations and his auditory perceptions. L.A. Chistovich conducted experiments that showed that the auditory canal of sensory corrections plays an important role in the regulation of the speech process. The subject in these experiments heard all the words he spoke with a delay of tenths of a second, which was achieved through the use of special sound recording equipment and headphones. When the direct connection between speech articulations and auditory perceptions was thus disrupted, the subject’s speech became extremely difficult, lost its involuntary and smooth character, and often completely disintegrated.

Vision is involved in sensory corrections of many movements. J. Gibson proposed to call this function visual kinesthesia. As the observer moves around in his environment, the irritation of his visual analyzer continuously changes. However, these changes in optical stimulation are not perceived by him as movements of visible objects, that is, as exteroception. They perform the function of visual kinesthesia and serve to control movements (Fig. 51).

During weapon actions and various manipulations with objects, an important role belongs to touch. Thus, most types of exteroception perform at least two different functions: they serve not only to reflect the external world, but also to regulate the movements of the body.

On the other hand, as already noted, complex forms of objective reflection are inextricably linked with the active movements of the subject, and therefore with proprioception. These movements perform the function of effector corrections of the image in the process of perception. To check the adequacy of the image, it is necessary to compare it with the reflected object. The simplest way of such comparison is external motor perceptual action. If necessary, the image is corrected. Different levels of perceptual tasks correspond to different levels of effector corrections.

An evolutionary classification of sensory processes, also emphasizing their level structure, was proposed in 1920 by the English neurologist H. Head. He distinguishes between epicritic and protopathic sensitivity. Younger and more advanced epicritic sensitivity allows you to accurately localize an object in space, it provides objective information about the phenomenon. For example, touch allows you to accurately determine the location of a touch, and hearing allows you to determine the direction in which the sound was heard. Relatively ancient and primitive protopathic sensations do not provide precise localization either in external space or in the space of the body. They are characterized by constant affective overtones; they reflect subjective states rather than objective processes.

H. Head proved that protopathic and epicritic components can occur within the same modality. He cut a branch of the cutaneous nerve on his hand and observed the progress of the restoration of sensitivity in the corresponding area of the skin. During the first month there was no sensitivity in this place. After about six weeks it appeared, but only in the form of protopathic sensitivity. The sensations of touch were diffuse and non-localized, but always either pleasant or unpleasant. Only six months later, the affective tone of the sensations disappeared, and they began to be perceived as touches addressed to a given area of the skin. Lastly, the perception of the direction of movement on the surface of the skin and the ability to determine the shape of objects were restored.

The ratio of protopathic and epicritic components in different types of sensitivity, naturally, turns out to be different. Interoception, for example, is a completely protopathic sensation. In Fig. Figure 10 schematically shows the relationships of their components within the five main types of exteroception. The diagram shows that younger, distant modalities are associated mainly with epicretic sensitivity.

The data presented indicate that the idea of an unambiguous connection between the receptor and the function it performs is erroneous. The analyzer, as is known, has a systemic, complex structure. At each level of perceptual actions, an adequate reflection of reality is achieved, be it a picture of muscle tension or a Paganini violin concerto. Perceptual systems are a set of hierarchical perception mechanisms capable of solving perceptual tasks of varying complexity. Perceptual systems are formed in the process of activity, which determines the variability of the links included in them. In the following, five main perceptual systems will be discussed in detail:

- The visual system implements a complex epicritic form of sensitivity. It takes part in the regulation of locomotion and objective actions. Vision plays an important role in the perception of space. This system allows you to evaluate the properties of the surface of an object, and also provides higher forms of object perception, which are distinguished by high constancy.

- The auditory system provides information about the properties of acoustic phenomena and the position of sounding objects in space. It is involved in the coordination of articulatory movements. Finally, the auditory system is associated with the most complex types of social perceptions - the perception of speech and music.

- The musculocutaneous system consists of many subsystems. It is involved in the regulation of movements and determines the perception of the relative position of body parts. On the basis of active touch, higher forms of objective perception are possible. The functioning of the musculocutaneous system is controlled by the visual system.

- The olfactory-gustatory system makes it possible to perceive the chemical properties of various substances. In some animals it is used for spatial orientation. However, this system plays the greatest role in controlling eating behavior.

- The vestibular system reflects the forces of gravity and inertial forces acting on the body associated with its accelerated movement. With its help, the position, posture, beginning and end of body movement in various directions are assessed. The vestibular system interacts with most other perceptual systems.

Chapter 15. Perceptual Processes

IN MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES

15.1. The concept of perceptual processes

Perception,

or

perception,

are the processes of reflection of objects or phenomena with their direct impact on the senses.

There are different types of perception depending on which analyzer (sensory organ) plays the leading role in it - visual, auditory, tactile, kinesthetic , olfactory, gustatory.

Depending on the form of existence of matter, they distinguish between the perception of

space, direction, magnitude

(which, in turn, distinguishes the perception of shape, distance, depth, perspective, etc.) and the perception

of time.

Perception is divided depending on the degree of complexity, the deployment of its process itself:

simultaneous

(“single-stage”, instantaneous) and

successive

(relatively divided into micro-stages), as well as according to the degree of awareness -

voluntary and

involuntary

perception

.

Perception has a number of basic properties: objectivity, integrity, structure, meaningfulness, selectivity, constancy, dependence

on a person’s past experience

(apperception), limited volume.

The process of perception includes a number of stages (phases of perception) that naturally replace each other:

detection, discrimination, identification, categorization, recognition, recognition.

All these types, properties, phases, patterns are preserved in management activities, providing an adequate and meaningful, substantive and structured reflection of external information.

They form mechanisms for the formation of sensory experience

. For example, the property of selectivity of perception plays an important role, ensuring the identification of the most significant features of the external situation. No less important is the property of structure, which allows us to perceive situations holistically (panoramic), but at the same time internally ordered. The property of apperception ensures constant “linking” of perceived information with professional and personal experience, as well as its “decoding” - decoding.

Individual style differences in perception also play a certain role in management activities. There are two main styles - analytical

and

synthetic

and two additional ones - analytical-synthetic and emotional.

“Synthetics” are characterized by a tendency to generalize reflection of phenomena and to determine their general, basic meaning. “Analysts,” on the contrary, are characterized by a tendency to highlight parts, details, details. The analytical-synthetic type is characterized by a combination of these features, however, with less severity of both. The emotional type is characterized by an increased sensory reaction to a situation, which, as a rule, interferes with its adequate perception. Of course, the third, analytical-synthetic, type of perception is the best for management activities; the first two are less effective; the fourth acts as a contraindication to management. Finally, among the general characteristics of perception, it is necessary to note such an important individual feature as observation. This is a general characteristic of perception, derived from all its other features. It consists of selective, arbitrary, meaningful and linked to an assessment based on past experience, recording the important and most significant features of the situation. In relation to management activities, it is customary to talk not just about observation, but about “sophisticated observation-technique”

(B.M. Teplov) as an important quality of a leader.

15.2. Specificity of perceptual processes in management activities

It is determined by two main circumstances. Firstly, perception is inextricably linked with all other cognitive processes (primarily with memory, thinking), which is expressed in its property of apperception, its dependence on professional management experience. It, in fact, merges with them and acts not just as a reception of information, but also as its assessment, comprehension, and formation of an attitude towards it. The complex nature of management activity to the maximum extent requires the synthetic participation in it of all cognitive processes. Because of this, perception in management activities is interpreted quite broadly - in its relationships with all other cognitive processes. It is very difficult (and not necessary) to “forcibly” isolate it from the general information interaction of the manager with the external environment. For example, a typical approach is that perception is defined as “the intellectual awareness of stimuli derived from sensations” [113].

Secondly, these stimuli themselves are the “material” of perception. The activities of a leader are extremely specific. The information of perception is not so much objects - objects

the external world (although, of course, they too), as

subjects

are individuals in all the diversity and inconsistency of their qualities, characteristics, properties, intentions.

Thus, perception in the activities of a leader is, first of all, personal, subjective (more precisely, interpersonal) perception. The subject of perception is such a complex and specific object, identical in its parameters to the very subject of perception, which is the “other person”. Therefore, the specificity of perceptual processes in management activities is that here they appear in their own special form - as interpersonal perception, as social perception.

The term “social perception” was proposed by the American psychologist J. Bruner in 1947 to refer to the perception of “social objects”,

by which were meant other people, social groups and even “large social communities”1.

Social perception covers a wide range of phenomena—its varieties. This is, firstly, individual

perception (the perception of a person by a person).

It depends on whether the person belongs to the same group as the perceiver or to another group (the “friend or foe” phenomenon). This is, secondly, the individual’s perception of certain groups

as a whole, which is also different in relation to his own and out-groups.

Finally, thirdly, this is the so-called intergroup

perception of each other by groups, as well as

self-perception

of itself. All these types of social perception literally permeate the content of management activities and form the basis of its communicative function. They, however, are supplemented by another important factor - the specificity of perception, depending on which plane - subordinate or coordination - they unfold. These are differences in social perception along the “vertical” and “horizontal” sides. When studying the processes of social perception, a large array of specific results was obtained, and many interesting patterns were discovered. To characterize the activities of a manager, the following data are most significant.

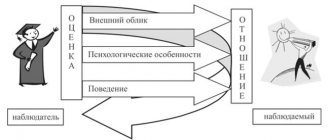

Firstly, this is a characteristic of the general structure of the process

social perception and its main components.

They are: the perceiving subject

(individual or group), the perceived

object

(another subject or group),

the process

of perception itself (receiving information),

decoding

information and creating an image of the “other”, active

actions to search for

additional information about the object of perception,

correction

(when necessary) of the original image. This process involves the involvement of rather complex psychological mechanisms - in particular, identification, empathy, reflection, standardization, stereotyping, which will be discussed below.

Secondly, it is the disclosure of the connection between the accuracy of social perception and the effectiveness of a leader.

The processes of interpersonal perception are a necessary

condition

for any joint, including managerial, activity. In general, it is shown that there is a rather complex, nonlinear relationship between accuracy, differentiation of social perception and the effectiveness of group activity; between these same parameters of perception and the success of management activities. Too low accuracy and completeness of perception, just like too high one, is accompanied by less successful activity. Success is maximum at a certain, rather high, but still intermediate value of perception accuracy. Regularities of this kind characterize the relationship of the optimum (and not the maximum - “the more, the better”)1.

The processes of social perception of a leader, as well as the nature of their connection with the effectiveness of his activities, are influenced by the marginality of his status. At the same time, two groups of managers are distinguished: those focused on the requirements of higher levels of the organization and those focused on the managed group (subordinates). The second type is characterized by greater accuracy of perception and its stronger influence on the effectiveness of activity. In general, the following main features of the leader’s perception of his subordinates are identified [70]: 1) transfer of the general impression of the subordinate to the assessment of his individual characteristics - both business and personal (“generalization effect”); 2) overestimation of those subordinates who support the leader; 3) overestimation of those subordinates who express opinions similar to the leader; 4) underestimation of those subordinates who do not support the leader and express judgments that contradict his opinion; 5) the manager blocks information coming to him from people who have received a negative assessment from him.

In this regard, another important question arises: about the adequacy of the leader’s perception of the group he leads. It is especially important for effective leadership, since the effectiveness of joint activities decisively depends on how “accepted” the leader is by the group (organization). Foreign studies have developed a kind of standard for how a leader should be perceived by his subordinates in order for his activities to be effective: firstly, as “one of us”; secondly, as “like most of us”; thirdly, as “the best of us”; fourthly, it must “correspond to expectations”, i.e. meet the expectations of group members. The most studied and richest in factual material is the area of social perception that is associated with the description of its main phenomena,

effects, manifestations (“phenomenological direction”). All these effects and phenomena have one thing in common. They are at the same time a kind of “errors” (a manifestation of inaccuracies in social perception), and the most important patterns, the causes of which are rooted in the fundamental characteristics of the psyche. Let us note those of them that are of the greatest interest and significance for characterizing management activities.

"Halo effect"

(haloeffect) is the most famous among all the “errors” of interpersonal perception. Its essence is that the general favorable impression (opinion) of a person is transferred to the assessment of his unknown traits, which are also perceived as positive. Conversely, a general negative impression also leads to a negative evaluation of those traits that are unknown. This effect increases with a decrease in general awareness of the object of perception; in this case, it itself serves as a kind of means of replenishing the lack of information about the object.

"Primacy Effect"

consists in a tendency to a strong overestimation of the first information about a person, in its fixation and high stability in the future in relation to other information received later. It is also called the “acquaintance effect”, or “first impression”. As research shows, this initial information is extremely important subjectively; it receives a subjective assessment disproportionate to its objective importance and is very difficult to correct in the future. This effect is based primarily on unconscious evaluation mechanisms. However, it has been shown that in a significant proportion of cases this effect is by no means just an “error”, since it gives, although a rough, approximate, but still quite accurate result1.

"Novelty effect"

unlike the previous one, it does not refer to the perception of a stranger, but to the perception of an already familiar person.

It consists in the fact that the latter, i.e. newer information turns out to be subjectively the most significant. “This

applies not only and further not so much to information about the external characteristics of the subject, but also to his, for example, speech behavior. Therefore, there is a rule according to which the conversation should end with some effective phrase, since it is this that is best captured by the interlocutor and most of all influences his opinion and behavior.

The last two effects are due to a common psychological mechanism— the mechanism of stereotyping.

All phenomena caused by it are sometimes separated into a separate group - the group of

“stereotyping effects”.

A stereotype is some stable image of a phenomenon or person, which is used as a means, a kind of “shortcut”, a scheme when interacting with these phenomena. It arises on the basis of “common” ideas about the essence of certain phenomena that have developed in everyday life (or in professional activity). It also arises on the basis of limited past experience, as a result of the desire to draw conclusions on the basis of limited information. Very often, the effects of this group arise in relation to group or professional affiliation (“all accountants are pedants”), but often also on the basis of purely everyday ideas (“fat people are good-natured, thin people are bilious”)1.

Stereotyping as a mechanism and reason for the group of effects that arises on its basis cannot be assessed from the standpoint of “good or bad.” It is twofold: by simplifying the process of perception, a person unwittingly “pays” for this simplification with the probability of erroneous perception. One of the relatively independent varieties of this phenomenon is the so-called modeling errors.

This is an image, a certain model of a person, formed on the basis of stereotypes and arising even

before the start of

interpersonal interaction, on the basis of preliminary information about him.

Modeling errors, therefore, arise on the basis of an incompletely adequate pre-perceptual setting.

It is not entirely adequate because it is formed under the influence of stereotyping.

In this regard, the experiments of the domestic psychologist A.A. became textbook. Bodaleva. Students in two groups were shown the same photograph of a man; one group was previously informed that this was a “hardened criminal,” and the other that this was a “prominent scientist.” They were then asked to describe the person in the photo. The results were diametrically opposed and fully consistent with the pre-perceptual setting. Not only as a whole, but also in individual parts, the face of the photograph was interpreted in accordance with it. Thus, “deep-set eyes” testified to either “deeply hidden anger” or “deep intelligence”, and a massive chin protruding forward - either “determination to go to the end in a crime”, or “willpower on the path of knowledge”.

A particular type of modeling error, but important specifically for management activities, is a kind of “ technocratic perception”

subordinates.

The manager “models” the subordinate on the basis of his official and professional affiliation and builds the image as he should be, based on this affiliation, and not on the basis of the characteristics of the real person. This phenomenon is a particular manifestation of the general technocratic, manipulative

leadership style. It is often a source of interpersonal conflicts in the “manager-subordinate” vertical. From here follows the well-known rule of humanistic management: one must see a person in a subordinate, and not a subordinate in a person; to lead not positions, but people.

"The Leniency Effect"

consists of an unreasonably positive perception by the leader of his subordinates and exaggeration of their positive traits while underestimating the negative ones;

in the opinion that they will “get better.” Its basis is the desire to protect oneself from possible conflicts that inevitably arise during an objective assessment of negative traits. This effect is more often observed among leaders of democratic and especially permissive styles. For leaders of an authoritarian style, it “turns around” and appears as the “hyper-demanding effect,”

or the “prosecutor effect.”

The effect of “physiognomic reduction”

consists of a not entirely justified and, as a rule, hasty conclusion about the internal psychological characteristics of a person based on his external appearance [70].

the “effect of negative asymmetry of initial self-esteem”, is more complex and has a group conditionality.

(OANS) [70]. Initially, it is the other group (“They”) that has more pronounced qualitative certainty in perception than its own group (“We”). But in the future, the first is assessed worse and less accurately than the second (one’s own). This is one of the typical sources of behavior of a leader who sets “other” individuals and “other” groups as an example to his subordinates, but does not adequately assess the advantages of “his” group—“not seeing a prophet in his own country.”

A kind of “mirror” version of this phenomenon is the opposite effect: polarization with a “plus” sign of the assessments of members of one’s own group (“We are overestimation”) and with a “minus” sign of members of the out-group (“They are underestimation”). This effect is based on a mechanism for strengthening the group’s self-identity, emphasizing its significance and value, and, consequently, one’s importance as its leader.

Such polarization is a special case and at the same time one of the reasons for a more general phenomenon, which is called the phenomenon of “in-group favoritism.”

It consists of the tendency to favor in perception and value judgments members of one's own group as opposed to members of some other group (or groups).

This phenomenon, as it were, sets the “most favored nation regime” for interpersonal relationships and perceptions of members within the group (compared to intergroup connections). In terms of the relationship between the leader of a group (organization) and his subordinates, he acquires additional specific features. Firstly, he can become, and most often becomes, selective in relation to individual members of the group. Secondly, at the same time it hypertrophies, transforming into the well-known phenomenon of protectionism,

i.e. moves from the plane of perception to the plane of action.

The phenomenon of “presumption of reciprocity”

(illusion of reciprocity) lies in a person’s stable tendency to perceive the attitude towards him from the people around him as similar to his own attitude towards them.

The reason for the phenomenon of “presumption of reciprocity” is that exactly this is similar, i.e. equal treatment, subjectively presented as the most “fair”. The assumption of reciprocity is a kind of “starting point” from which interpersonal relationships begin to be built. For a manager, it is at the same time a regulator—a restraining mechanism. It forces him to remember that unfair assessments can cause a “boomerang effect”

on the part of subordinates.

The phenomenon of “assumption of similarity”

consists in the tendency of the subject to believe that other people significant to him perceive others in the same way as he does. He transfers his perception of other people onto his subordinates. Thus, a leader is inclined, as a rule, to believe that his subordinates’ perception of both other people and himself is exactly the same as his own perception. Moreover, he will structure his behavior and relationships with subordinates in such a way as to cultivate and strengthen this “unity of perception and assessments.” In extreme terms, this phenomenon can also go beyond perception and transform into the phenomenon of imposition of opinions. Two more phenomena—the “mirror image” and favoritism—have similar content and are as follows. Members of two groups (usually in conflict) perceive the same personality traits as positive in members of their own group and as negative in members of the other group.

A characteristic “error” of perception, which, however, is caused not only by personal factors, but by more general factors, is the phenomenon of ignoring the informational value of “what did not happen.”

Any leader knows well that often what is much more important is not what a person said or did, but what he did not say or do. In practice, however, this understanding is not always supported by actions due to the specified effect. Moreover, “information about what did not happen” is not only underestimated, but is often ignored as not occurring and therefore not taken into account at all1. Everyone knows the expression “silence is a sign of consent” as the simplest case of this phenomenon. In management, however, it is often quite complex and requires special understanding. Underestimating this very often leads to mistakes in management. The reason for this phenomenon is that the interpretation and understanding of “information about what did not happen” is more difficult and, therefore, complicates the already complex activities of the manager. At the same time, one of the most important features of a leader’s professional competence and “experience” is precisely the correct assessment of what could have happened, but did not happen, and why it did not happen.

The considered phenomena of social perception reveal the specificity and complexity of perceptual processes in management activities. Along with them, another category of phenomena of interpersonal perception plays a significant role in the activities of a leader. It, however, is more general in nature and is closely related to intellectual processes. These phenomena characterize not only how people perceive and evaluate others, but also how they try to explain the reasons

the actions they perceive, the behavior of others.

In Western psychology, this direction was called causal attribution 1 ,

developed in the works of F. Heider, E. Jones, L. Ross, R. Nisbett and others.

The basic and original phenomenon of causal attribution is that people tend to attribute their behavior to situational factors.

(i.e., the influence of “circumstances”) on them, and the behavior of others - by

personal factors

(i.e., their psychological characteristics)2. This tendency is general in nature, although it depends on the “sign” of the behavioral event being assessed—its success or failure. In case of failure, it is maximally expressed, and in case of success it can change to the opposite. This reveals another fundamental feature of attribution. People tend to explain personal successes by their personal traits, their attitude to business, and failures by circumstances, external reasons. The basis of all these phenomena is the human desire not only to perceive events as such, but also to try to explain them, to identify their causes. The search and discovery of these reasons occurs, however, on different planes, depending on whose actions are to be explained - “myself”, “my actions” or “others” and their actions.

Attribution permeates literally all management activities and is especially important for the implementation of the evaluative functions of a manager. At the same time, in his activity it becomes more complex and acquires additional features. The fact is that in this activity two different directions of attribution collide. The leader, according to the general law of attribution, is inclined to explain the failure of any event by reasons external to it. But they will precisely be “others” - people external to him (subordinates). However, subordinates themselves also act according to this law, explaining the general failure also by external factors - poor leadership, unsuccessful organization. Such a clash is one of the most important and most typical causes of conflicts along the leader-subordinate line, rooted in the psychological mechanisms of attribution. The way these conflicts are resolved, as well as the leadership style in general, is significantly influenced by a specific personal quality associated with the attribution process - locus of control.

personality.

It consists in the general tendency of the subject to attribute the causes of events and his actions primarily to either external or internal factors. A person can localize these reasons in different ways - factors that determine and explain (“control”) certain phenomena. This is where the term “locus of control” comes from. Depending on this, two types of personalities are distinguished - internal and external. Internals

are characterized by an internal locus of control;

They are characterized by a desire to explain events by internal factors (their personal characteristics, motivation, diligence, knowledge). Externals

have an external locus of control; characterized by a tendency to “externalize” causes outside oneself and explain phenomena by external factors. They may be circumstances, the influence of other people, bad luck (or luck), lack of funds and time, etc.

All the considered patterns and effects of the social-perceptual plan in the activities of a leader are determined by the specifics of the main object of his managerial influences - the personalities of the people subordinate to him. At the same time, no matter how complex and specific this “social object” of perception may be, it does not exhaust the content of all the information that a manager has to perceive. The main feature of management information (or, using psychological terminology, the information basis of activity

leader) - its huge volume.

This feature is inextricably linked with another important feature of management information - its fundamental heterogeneity and different quality

of content.

It includes diverse categories of information sources - information about subordinates, about technology, “about facts” (events), “about opinions”, about the current state of the organization, about forecasts of events, directive and normative information and much more. The fundamental heterogeneity of the information base is due to the main property of organizational management systems - their complex, sociotechnical type.

Therefore, the information basis of a manager’s activity places particularly stringent and specific requirements on the process of perception as a whole as a means of obtaining information.

The essence of these requirements is connected with the following contradiction. On the one hand, the manager “must see everything,” preferably not only in general, but also in detail (the requirement of “sophisticated observation”). On the other hand, the most important psychological feature of perception—the limited scope of it—does not allow this to be achieved. The way out of the situation is that the information basis of the manager’s activity is subject to natural transformations and a special organization. They occur on the basis of features specific to the process of perception. The main ones among them are integrity, structure, selectivity, objectivity of perception. Therefore, the perceived information is subject to structuring, dividing into parts, highlighting the main ones, comprehension, grouping, systematization - in other words, it is organized

in accordance with the characteristics of perception. The leading role in this organization is played by the property of apperception of perception - the connection of currently perceived information with a person’s past experience. Therefore, the very perception of information by a leader is inseparable from his professional experience; it is organized and directed by him. The measure of accuracy, adequacy and completeness of information perception therefore very much depends on the characteristics of the professional experience and knowledge of the manager1. Such an organized, meaningful information base is perceived easier, more adequate, more complete and faster. In psychology, there are two main means of ensuring the structuring of the information basis of professional activity.

The first of these means is the “operational perception units” (OPUs). Operational units are understood as any objects or their groups that are subjectively perceived as integral

and

meaningful,

separate from other objects.

These are like “pieces”, blocks of information; those structural elements into which the subject arbitrarily divides the huge information flow that affects him. Operational units do not necessarily include any one object (or attribute) or individual person. Operational units are “many things perceived as one” - as one semantic object. For example, for a senior manager, such an operational unit may not be each individual member of the organization, but a group, a division as a whole. But this is no longer typical for the primary leader: his operational units should be more fractional. Operating units undergo organization: they are ordered, their comparative importance is determined, their hierarchy is built, they are specified and often enlarged. Because of this, the entire information basis of a manager’s activity is an orderly and organized system of operational units. Operational units can vary greatly in volume, in their “capacity” and information capacity. To an extremely minimal extent, it can be, for example, one or another personal characteristic of a subordinate perceived by the manager. In an extremely general form, it can be, for example, information about the state of the socio-psychological climate in any large unit. The manager perceives it and takes it into account in his work as one

of the information signs.

Thus, their information capacity and value depend on the size of operational units - the extent to which they fulfill their main role - organizing and structuring the information base. Ultimately, the total volume of the information basis of the manager’s activities depends on the size of the operational units1. The size of operational units is the size of the “package” that is used to organize information about the organization. At the same time, operational units must be adequate

to the objective content of external information.

This means that they are built on the basis of real, inherent features of the organization and reflect its technological and structural features. Finally, operational units must be dynamic.

If necessary, they must allow either splitting into smaller units (decomposition) or enlargement (synthesis) into even larger units. Thus, the general structure of all operational units provides a “general view” of the organization, a panoramic vision of it, and the ability to “disaggregate” these units provides a vision of details, “subtleties” (“sophisticated observation”). The system of operational units is a means of seeing “both the forest and individual trees” at the same time [58]. The higher the hierarchical level of the manager, the larger, more generalized, less detailed the operational units and vice versa. Operational units are not specified from the outside, but are formed by the subject himself. They are a product of the formation of professional experience as a whole, but at the same time they are an indicator of its maturity.

The second means of “fighting” information redundancy is the mechanism of forming an operational image of the managed object (organization)2. An operational image is an integrated, meaningful and orderly system of operational units that presents generalized information about the main features of the organization. The operational image, as a special psychological formation formed on the basis of the main laws of perception, is characterized by a number of important laws and properties. The main ones among them are the following [72].

Integrity.

An operational image is always a generalized image of an organization, the individual components of which are structured and synthesized.

This property provides that “overall vision” of the organization, which is so necessary for the leader - the

panoramic perception of the leader, the ability to “keep the general picture of what is happening before the mental gaze.”

Schematized.

An operational image is not only information about individual features of an organization, but also about the connections between them, i.e. about its structure. Therefore, firstly, it includes these structural relationships in a schematic, visual form. Secondly, its content is also schematized - simplified, abstracted from minor details.

Conciseness.

The operational image, due to its schematization, as well as for reasons of convenience of working with it, tends to become more and more compact and, therefore, easier to work with. Hence the term “operational” itself - it means convenient to use, most suitable for accurate, fast and effective use. It is becoming more and more concise, which, however, is achieved not due to “information losses”, but due to better organization of information in the image.

Pragmatism.

The operational image is formed under the direct influence of the main management tasks and goals of the organization.

It initially adapts to them, is formed in the form that best suits them. It includes only that information that contributes to the goals and objectives of the organization, and all other information is excluded. In this regard, to characterize operational images in the activities of a leader, the concept of de-directed perception

[M. Arbib]. This is perception, the process and result of which (image) is subject to the achievement of a goal, specific actions to implement it [4].

Functional deformation.

In the structure of the operational image, those components that are most important for achieving the organization’s goals come to the fore and become hyper-emphasized.

All others are subjectively underestimated, and often completely ignored. Dynamism.

The operational image, being quite stable, should not be “rigid” at the same time.

It must allow for the possibility of transformation when external conditions change. Thus, the operational image also acquires the property of adaptability

- adaptability to situational changes in operating conditions.

So, the main features of perceptual processes in management activities are determined by the originality of the main object of perception - a person, as well as the heterogeneity and volume of perceived information. The numerous phenomena and patterns of social perception that arise in this case reveal the essence of the perception process in the activities of a leader. These phenomena, interacting with general perceptual patterns, determine the generalized means of organizing managerial perception - the formation of operational units of perception and operational images.