Where do emotions come from?

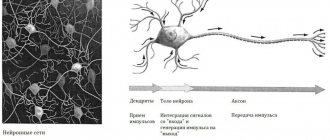

The limbic system is a group of interconnected structures located deep within the brain. This is the part of the brain that is responsible for behavioral and emotional reactions.

Scientists have not agreed on a complete list of structures that are part of the limbic system, but some of them definitely belong to it:

- Hypothalamus . In addition to controlling emotional responses, the hypothalamus is also involved in sexual responses, secreting hormones, and regulating body temperature;

- Hippocampus . The hippocampus helps store and retrieve memories. It also plays a role in remembering and encoding the environment (spatial memory);

- Amygdala . The functions of the amygdala are associated with ensuring defensive behavior, vegetative, motor, emotional reactions;

- Limbic cortex . This part contains two structures: the cingulate cortex and the parahippocampal gyrus. Together they influence mood, motivation and judgment.

The size of the amygdala has been suggested to be associated with aggressive behavior - that is, "withdrawal" (illustration from howstuffworks.com)

Play by the rules

The balanced work of all systems of our body has been formed over thousands of years; many mental processes are subject to physiological mechanisms of internal regulation. These are the rules that were established by nature in a game called “Evolution”; you need to know them in order to be able to manage your condition and not allow external factors to influence it. The remote control of the body and consciousness is in our hands, the reaction to emerging situations must be under the conscious control of the brain, and not become a reflexive stereotype in response to external stimuli, then we will not be able to be controlled from the outside. Always keep in touch with sensations - by their signals you can understand what is happening in the body and whether you need to react to it. After all, reaction is the key factor in defense without attack, and when there is no reaction, any provocations stop. And even if the hormonal mechanism of mental defense works, if you maintain awareness and stop emotional reactivity, you will come out of this game as a winner!

Which part of the brain controls fear?

From a biological point of view, fear is a very important emotion. This emotion helps to respond adequately to threatening situations that can cause harm.

Fear arises through stimulation of the hypothalamus by the amygdala. This is why some people with brain damage affecting the amygdala do not always respond appropriately to dangerous situations.

When the amygdala stimulates the hypothalamus, it initiates the fight-or-flight response. The hypothalamus sends signals to the adrenal glands to produce hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol.

When these hormones enter the bloodstream, several physical changes occur, resulting in an increase in:

- Heart rate

- Breathing rate

- Blood Sugar Level

- Sweating

There is nothing unnatural about fear. On the contrary, it is an instant activation of the body’s resources due to a long evolutionary path (illustration from howstuffworks.com)

In addition to initiating the fight-or-flight response, the amygdala also plays a role in fear learning. It refers to the process by which a connection develops between certain situations and feelings of fear.

Joy and laughter: prefrontal cortex and hippocampus

In joyful moments, the right amygdala becomes much more active than the left. Today, it is widely believed that the left hemisphere of our brain is responsible for logic, and the right hemisphere for creativity. However, we have recently learned that this is not the case. The brain requires both parts to perform most functions, although hemispheric asymmetries exist: for example, the largest speech centers are located on the left, while processing of intonation and accents is more localized on the right.

The prefrontal cortex is several areas of the brain's frontal lobes that are located at the front of the hemispheres, just behind the frontal bone. They are associated with the limbic system and are responsible for our ability to set our goals, make plans, achieve desired results, change course and improvise. Research shows that during happy moments in women, the prefrontal cortex on the left hemisphere is more active than the same area on the right.

The hippocampi, which are located deep in the temporal lobes, together with the amygdala, help us separate important emotional events from unimportant ones so that the former can be stored in long-term memory and the latter can be discarded. In other words, the hippocampi evaluate happy events in terms of their significance for the archive. The anterior insula cortex helps them do this. It is also connected to the limbic system and is most active when a person remembers pleasant or sad events.

Which part of the brain controls anger?

Like fear, anger is a reaction to threat or stress. When a situation occurs that seems dangerous and there is no way to escape, the body is likely to respond with anger or aggression. This can also be considered part of the fight or flight response.

Frustration, such as encountering obstacles in trying to achieve a goal, can also trigger anger.

Anger begins with the amygdala stimulating the hypothalamus, just like the emotion of fear. Additionally, the prefrontal cortex may also play a role in anger. People with damage to this area often have trouble controlling their emotions, especially anger and aggression.

Psychic protection

The mechanism of neural mental defense is very subtle; it is part of the protective adrenaline response to stress factors. During its activation, there is no need for an immediate threat; it is enough to cause a contradiction in the usual perception of the world. At the same time, the hormone norepinephrine (which is a precursor of adrenaline) is produced, which leads to the fact that not the whole body, but only the psyche, tenses up and comes into a protective state. No matter how valuable the information, in this state the brain cannot process it effectively; at the neurochemical level, it perceives it as a threat, even if it is simply someone's opinion or objective facts with which, under other circumstances, we might agree. As a result, instead of opportunities, a person sees obstacles, instead of developing his consciousness, he blocks it, taking an aggressive position towards others.

Aggression is needed to protect against attack, but under the influence of this ancient mechanism, formed historically, we unconsciously begin to defend ourselves psychologically and are hostile to what does not pose any threat to us. The brain processes information most effectively when there is no dissonance between the relatively recently formed cerebral cortex and more ancient structures such as the limbic system.

Which part of the brain controls happiness?

Happiness refers to a general state of well-being or satisfaction. When we feel happy, we usually have positive thoughts and feelings.

Neuroimaging shows that happiness occurs partly in the limbic cortex. However, the upper part of the parietal lobe, which is responsible for spatial analysis, has something to do with this.

A 2015 study found that people with more gray matter in the right superior parietal lobe were happier. Experts believe that the upper part of the parietal lobe processes certain information and turns it into feelings of happiness. For example, imagine that you had a wonderful night with someone you care about. Later, when you remember this experience, you may feel a sense of happiness.

It is worth mentioning here such a neurotransmitter as serotonin, its participation and normal concentration in certain areas of the brain contributes to a sense of well-being. It’s not for nothing that this neurotransmitter is called the “hormone of happiness.”

The part of the brain responsible for the emotional component of moral and ethical assessments has been identified

Some parts of the brain that are somehow associated with emotions: 1 - orbitofrontal cortex, 2 - lateral prefrontal cortex, 3 - ventromedial prefrontal cortex, 4 - limbic system. (Figure from thebrain.mcgill.ca)

American psychologists have discovered that patients with bilateral damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex are guided only by reason when solving complex moral dilemmas, while in healthy people emotions play an important role. In imaginary situations, the patients studied do not see the difference between a murder committed in absentia (for example, by pressing a button) and one committed by oneself, while to healthy people the difference seems enormous. Perfectly distinguishing between good and evil on a conscious level, such patients are incapable of empathy and never experience feelings of guilt.

Eric Kandel, who received the Nobel Prize in 2000 for his research into the molecular mechanisms of memory, was interested in psychoanalysis in his youth and became a neuroscientist in the hope of finding out in which parts of the brain Freud's "ego", "superego" and "id" are localized (which, however, he did not managed). Half a century ago, such dreams seemed naive, but today neuroscientists have come close to identifying the biological basis of the most complex aspects of the human psyche.

An article by American psychologists and neuroscientists published in the latest issue of the journal Nature

, reports important progress in the study of the material nature of morality and morality, that is, that aspect of the psyche that Sigmund Freud called the “superego” (super-ego). Freud believed that the superego functions largely unconsciously and, as it turns out, he was absolutely right.

Traditionally, it was believed that morality and morality stem from a common sense of socially accepted norms of behavior, from the concepts of good and evil learned in childhood. However, in recent years, a number of facts have been obtained indicating that moral assessments are not only rational, but also emotional in nature. For example, various disturbances in the emotional sphere are often accompanied by changes in ideas about morality; when solving problems related to moral assessments, the parts of the brain responsible for emotions are excited; Finally, behavioral experiments show that people's attitudes toward various moral dilemmas are strongly influenced by their emotional state. However, until now no one has been able to experimentally show that some area of the brain that specializes in emotions is actually necessary for the formation of “normal” judgments about morality.

The authors of the article studied six patients who suffered bilateral lesions of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPC) in adulthood. It is known that this part of the brain carries out an emotional assessment of sensory information entering the brain, especially that which has a “social” connotation. The VMPC also regulates the body's emotional responses (for example, an increase in heart rate when seeing a photograph of someone's suffering).

The patients were carefully examined by qualified psychologists and neurologists, and the examination was carried out “blind”: the doctors did not know what scientific ideas would be tested based on their conclusions. It turned out that all six retained a normal level of intelligence (IQ from 80 to 143), memory and emotional background (that is, no pathological mood swings were detected). However, their ability to empathize was sharply reduced. For example, they almost did not react (on a physiological level) to “emotionally loaded” pictures depicting various disasters, crippled people, etc. Moreover, all six patients, as it turned out, were practically incapable of feeling embarrassment, shame and guilt. At the same time, on a conscious level, they perfectly understand what is good and what is bad, that is, the accepted social and moral norms of behavior are well known to them.

Subjects were then asked to make judgments about various imaginary situations. There were only 50 situations, and they were divided into three groups: “extra-moral”, “moral impersonal” and “moral personal”.

Situations from the first group do not require the resolution of any conflicts between reason and emotions. Here is an example of such a situation: “You bought several pots of flowers at the store, but they all don’t fit in the trunk of your car. Will you take two flights to avoid staining the expensive back seat upholstery?”

Situations in the second group involve morality and emotion, but do not cause strong internal conflict between utilitarian considerations (how to maximize the “total good”) and emotional restrictions or prohibitions. Example: “You are on duty at the hospital. Due to the accident, poisonous gas entered the ventilation system. If you do nothing, the gas will enter the room with three patients and kill them. The only way to save them is to turn a special lever that will direct poisonous gas into the room where only one patient lies. He will die, but those three will be saved. Will you turn the lever?

The situations of the third group required the resolution of an acute conflict between utilitarian considerations about the greatest common good and the need to perform an act with one's own hands against which emotions rebelled. For example, it was proposed to personally kill some stranger in order to save five other strangers. Unlike the previous case, where the death of the victim was caused by the “impersonal” turning of a lever, here it was necessary to push a person under the wheels of an approaching train with one’s own hands or strangle a child.

A complete list of all situations can be read here (Pdf, 180 Kb).

The responses of six patients with bilateral damage to the IMC were compared with the responses of two control groups: healthy people and patients with comparable damage to other areas of the brain.

Judgments regarding “non-moral” and “moral impersonal” situations in all three groups of subjects completely coincided. As for the third category of situations—“moral personal”—contrasting differences emerged. People with bilateral damage to the IMPC practically did not see the difference between an “absentee” murder with the help of some kind of lever and a personal one. They gave almost the same number of positive answers in situations of the second and third categories. Healthy people and those with damage to other parts of the brain were three times less likely to agree to kill someone with their own hands for the common good than “in absentia.”

In situations requiring the resolution of an acute conflict between reason and emotions (“moral personal” situations), people with bilateral damage to the IMC (1) gave positive responses much more often than healthy people (3) and than those with damage to other parts of the brain (2 ). Rice. from the discussed article in Nature

Thus, when making moral judgments, people with damaged VMPK are guided only by reason, that is, by “utilitarian” considerations about the greatest overall good. The emotional mechanisms that sometimes guide our behavior despite dry rational arguments do not function in these people. They (at least in imaginary situations) can easily strangle someone with their own hands if they know that this action will ultimately produce a greater output of “total good” than inaction.

The results obtained indicate that moral judgments are normally formed under the influence of not only conscious inferences, but also emotions. Apparently, VMPK is necessary for the “normal” (the same as in healthy people) resolution of moral dilemmas, but only if the dilemma involves a conflict between reason and emotions. Freud believed that the superego is located partly in the conscious and partly in the unconscious part of the psyche. To simplify somewhat, we can say that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the emotions it generates are necessary for the functioning of the unconscious fragment of the superego, while conscious moral control is successfully carried out without the participation of this part of the cortex.

The authors note that their conclusions should not be extended to all emotions in general, but only to those associated with sympathy, empathy or personal guilt. Some other emotional reactions in patients with damage to the IMPC, on the contrary, are more pronounced than in healthy people. For example, they have a reduced ability to control anger and become angry easily, which can also affect decision-making that affects morality (see: Michael Koenigs, Daniel Tranel. Irrational Economic Decision-Making after Ventromedial Prefrontal Damage: Evidence from the Ultimatum Game // The Journal of Neuroscience

, January 24, 2007, 27(4): 951–956).

Source:

Michael Koenigs, Liane Young, Ralph Adolphs, Daniel Tranel, Fiery Cushman, Marc Hauser, Antonio Damasio.

Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments // Nature

. Advance online publication March 21, 2007.

Alexander Markov

Which part of the brain controls love?

It may sound strange, but the onset of romantic love is associated with stress caused by the hypothalamus. This is why when you are in love and think about the object of your love, you experience excitement and anxiety.

As these feelings intensify, the hypothalamus triggers the release of other hormones such as dopamine, oxytocin and vasopressin.

Dopamine is connected to your body's reward system. It helps make love a desirable feeling.

You can read more about dopamine in the article: “What is dopamine and how does it work”

In a small 2005 study, participants were shown a photo of a person they had a crush on. They were also shown a photograph of a person they knew. When shown the first photograph, the subjects showed increased activity in those parts of the brain that are rich in dopamine.

Oxytocin is often called the “love hormone.” This is mainly because its release increases when you hug someone or have an orgasm. It is produced in the hypothalamus and released through the pituitary gland. It is also about social connection, which is very important for trust and relationship building. Oxytocin may also promote feelings of calm and contentment.

Vasopressin is produced in the hypothalamus and released by the pituitary gland. Vasopressin is also involved in social bonding with a partner.

Tenderness and comfort: somatosensory cortex

Recently, British researchers were able to confirm the theory of the usefulness of affection using computed tomography. They found that the touch of other people causes strong bursts of activity in the somatosensory cortex, which is already working constantly, tracking all our tactile sensations. Scientists have come to the conclusion that the impulses that arise if someone gently touches our body in difficult moments are associated with the process of isolating from the general flow of critical stimuli that can change everything for us. Experts also noticed that the experiment participants experienced grief more easily when a stranger held their hand, and much easier when their palm was touched by a loved one.