What is recurrent depression?

Recurrent (lat. recurrens - “returning”) disorder is established when depressive episodes are repeated throughout the year with a certain frequency.

Each of them is associated with loss of interests, persistently depressed mood, and increased mental and physical fatigue. The ICD-10 code is F33. Between periods of exacerbation, a person feels absolutely normal (intermission). To make a diagnosis, symptoms must meet DSM-V and ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision) criteria.

It is important that there is no history of hyperactivity or inappropriately elevated mood associated with mania. When they appear, the conclusion is changed to “bipolar affective disorder” (F31. -).

Notes

- ↑ 1234

Disease ontology database (English) - 2021. - ↑ 1234

Monarch Disease Ontology release 2018-06-29sonu - 2018-06-29 - 2018. - ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 American Psychiatric Association.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). - Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. - P. 160-162. — 992 p. — ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. — ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. — ISBN 0-89042-554-X. - World Health Organization.

International Classification of Diseases (10th revision). Class V: Mental and behavioral disorders (F00-F99) (adapted for use in the Russian Federation). - Rostov-on-Don: “Phoenix”, 1999. - P. 156-157. — ISBN 5-86727-005-8. - Stahl SM, Morrissette DA, Faedda G., Fava M., Goldberg JF, Keck PE, Lee Y., Malhi G., Marangoni C., McElroy SL, Ostacher M., Rosenblat JD, Solé E., Suppes T., Takeshima M., Thase M.E., Vieta E., Young A., Zimmerman M., McIntyre RS

Guidelines for the recognition and management of mixed depression. (English) // CNS Spectrums. — 2021. — April (vol. 22, no. 2). - P. 203-219. - doi:10.1017/S1092852917000165. — PMID 28421980. [] - ↑ 1 2 Yu.V. Kannabikh.

History of psychiatry. - L.: State Medical Publishing House, 1928. - ↑ 1 2

FGBNU NTsPZ.

‹‹Depression in general medicine: A guide for doctors›› (undefined)

. www.psychiatry.ru. Access date: April 22, 2021. - Charles F. Reynolds, Vikram Patel.

Screening for depression: the global mental health context (English) // World Psychiatry (English) Russian.. - Wiley-Blackwell, 2017-10. - Vol. 16, iss. 3. - P. 316-317. - doi:10.1002/wps.20459. - Zung WW (1965) A self-rating depression scale. Archives of General Psychiatry 12: 63-70 PMID 14221692

- Beck AT et al. An Inventory for Measuring Depression //Archives of general psychiatry. - 1961. - T. 4. - No. 6. - pp. 561-571.

- PHQ-9 Screener-Phizer (undefined)

. - Bech P, Rasmussen NA, Olsen LR, Noerholm V, Abildgaard W. The sensitivity and specificity of the Major Depression Inventory, using the Present State Examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord 2001; 66: 159—164 PMID 11578668

- K Pajer et al.

Discovery of blood transcriptomic markers for depression in animal models and validation in subjects with early-onset major depression (English) // Translational Psychiatry (English) Russian. : journal. - 2012. - Vol. 2, no. e101. - doi:10.1038/tp.2012.26. - Podkorytov V.S., Chaika Yu.Yu.

Depression and resistance // Journal of psychiatry and medical psychology. - 2002. - No. 1. - P. 118-124. - ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Bykov Yu. V.

Treatment-resistant depression. - Stavropol, 2009. - 74 p. - Vereitinova V.P., Tarasenko O.A.

Side effects of antidepressants // Pharmacist. - 2003. - Issue. 14. - Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis: The Lancet

- Mosolov S. N.

Basics of psychopharmacotherapy. - Moscow: Vostok, 1996. - 288 p. - Combination of Antidepressant Medications From Treatment Initiation for Major Depressive Disorder: A Double-Blind Randomized Study (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Date accessed: February 21, 2021. Archived April 3, 2021. - Bykov Yu. V., Bekker R. A., Reznikov M. K.

Resistant depression. Practical guide. - Kyiv: Medkniga, 2013. - 400 p. — ISBN 978-966-1597-14-2. - Wiles N, Thomas L, Abel A, Ridgway N

et al .

Cognitive behavioral therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care based patients with treatment resistant depression: results of the CoBalT randomized controlled trial (English) // The Lancet. - Elsevier, 2013 Feb 2. - Vol. 381, no. 9864. - P. 375-384. - doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61552-9. - PMID 23219570. - Robert A. Bell, PhD, Peter Franks, MD, Paul R. Duberstein, PhD, Ronald M. Epstein, MD, Mitchell D. Feldman, MD, MPhil, Erik Fernandez y Garcia, MD, MPH and Richard L. Kravitz, MD , M.S.P.H.

Suffering in Silence: Reasons for Not Disclosing Depression in Primary Care (English) // Annals of Family Medicine: journal.

- 2011. - Vol. 9. - P. 439-446. - doi:10.1370/afm.1277. (PDF (unspecified)

. Archived May 30, 2012.) Abstract in Russian: Why are patients silent about depression?

(undefined)

. - Breslau, N. et al.

Headache and major depression

(undefined)

. Neurology (1999). Archived May 30, 2012. - Breslau, N. et al.

Migraine and Major Depression: A Longitudinal Study (English) // Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain: journal. - July 1994. - Vol. 34, no. 7. - P. 387-393. - doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3407387.x. - Psychiatric disorders among Egyptian pesticide applicators and formulators. By Amr MM, Halim ZS, Moussa SS. In Environ Res. 1997;73(1-2):193-9. PMID 9311547

- Depression and pesticide exposures among private pesticide applicators enrolled in the Agricultural Health Study. By Beseler CL, Stallones L, Hoppin JA, Alavanja MC, Blair A, Keefe T, Kamel F. In: Environ Health Perspect. 2008 Dec; 116(12):1713-9.PMID 19079725

- A cohort study of pesticide poisoning and depression in Colorado farm residents. By Beseler CL, Stallones L. In Ann Epidemiol. 2008 Oct; 18(10):768-74.PMID 18693039

- Mood disorders hospitalizations, suicide attempts, and suicide mortality among agricultural workers and residents in an area with intensive use of pesticides in Brazil. By Meyer A, Koifman S, Koifman RJ, Moreira JC, de Rezende Chrisman J, Abreu-Villaca Y. In J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2010; 73(13-14):866-77. PMID 20563920

- Suicide and potential occupational exposure to pesticides, Colorado 1990—1999, By Stallones L. In J Agromedicine. 2006; 11(3-4):107-12. PMID 19274902

- Increased risk of suicide with exposure to pesticides in an intensive agricultural area. A 12-year retrospective study. Di Parrón T, Hernández AF, Villanueva E. In Forensic Sci Int. 1996 May 17; 79(1):53-63.PMID 8635774

- Martha H. Vitaterna, Fred W. Turek, Andrew Kasarskis, John J. Renger, Christopher J. Winrow.

Cross-species systems analysis identifies gene networks differentially altered by sleep loss and depression // Science Advances. — 2018-07-01. - Vol. 4, iss. 7. - P. eaat1294. — ISSN 2375-2548. - doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat1294. - Vesga-López O., Blanco C., Keyes K., Olfson M., Grant BF, Hasin DS

Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. (English) // Archives Of General Psychiatry. - 2008. - July (vol. 65, no. 7). - P. 805-815. - doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. — PMID 18606953. [] - Depression: symptoms and treatment of depression

Reasons for development

It is still unknown what exactly leads to the formation of affective disorders (mood pathologies). The role of the following factors is suspected:

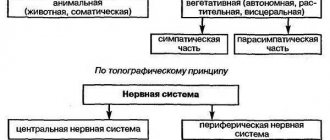

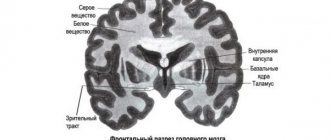

- genetically determined insufficiency of the activity of the main neurotransmitters of the central nervous system (norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, melatonin) - monoamine theory;

- psychosocial distress;

- reaction to a traumatic event (individual for a person);

- endocrine (hormonal) imbalance;

- the presence of somatic disability, for example, disability or severe chronic disease.

The occurrence of the first depressive episodes may be a response to external provocative events, usually psychological trauma. Repeated exacerbations usually have no connection with external conditions.

The majority of patients are women, but every year the number of men seeking help increases. Without treatment, 85% experience frequent relapses with a tendency to protracted course.

Screening

Screening tests are much better at identifying patients with depression than specially trained medical personnel. Studies in the United States and low- and middle-income countries have shown that volunteers and allied health workers (nurses, social workers) can be trained to screen for depression (as well as other mental disorders) using short questionnaires. In particular, in the United States, the question of introducing depression screening into the standard of care is being raised, but when conducting such screening, several questions arise at once - what criteria should be used when screening for depression, the method of screening, who should be screened and when. It is possible to offer annual screening to all adults who come to the doctor - but the number of patients may then significantly exceed the capacity for therapeutic intervention. An alternative approach is to screen high-risk groups (mothers of newborns, people with sleep disorders, chronic diseases, severe social stressors, or medically unexplained somatic complaints)[8].

Several screening instruments for depressive disorder have been developed over the years. These instruments include self-report tests such as the Zang Self-Rating Depression Scale[9], Beck Depression Inventory[10], PHQ-9 Questionnaire[11], and the Major Depression Questionnaire.[12]

| This section is not completed. You will help the project by correcting and expanding it. |

Symptoms

The recurrent nature of the disease is confirmed if the patient suffered at least 2 episodes (or one severe one), each of which lasted two weeks or more. In this case, a person must have intervals of normal life between exacerbations of at least two months.

A depressive episode has the following symptoms:

- The main ones: unexplained fatigue, a feeling of constant decrease in energy, the inability to experience positive emotions from previous activities (which previously brought joy), low mood.

- Additional: disturbances in appetite and sleep, a pessimistic view of the future, decreased self-esteem, uncertainty in all areas of life, deterioration in concentration, pathological ideas of guilt (self-deprecation).

- The symptoms are not caused by brain damage.

- Apart from depressive episodes, no hypomanic symptoms were noticed from the onset of the disease.

Clinical manifestations intensify closer to the morning. The resulting disturbances can affect libido, reduce mental and cognitive activity, and negatively affect performance. In severe cases, symptoms significantly impair social functioning; delusions, hallucinations, and stupor may occur.

After the end of the depressive episode, the patient returns to the previous level of life that was before the disease. In approximately 20-30% of cases, mild residual symptoms persist, which can be effectively relieved with therapy.

Signs of recurrent depressive disorder

The symptoms of recurrent depressive disorder are practically indistinguishable from those of classic depression. This is muscle and motor retardation, constant apathy. In this case, a person remains in a normal state for no more than 2 months.

The main difference between recurrent and psychogenic depression is the alternation of deep depression with periods when everything is completely fine in a person’s condition and life.

Experts consider the following to be classic symptoms of recurrent depressive disorder:

- Bad mood. A person stops receiving pleasure, no matter what happens in her life. At the same time, he may experience different states that depend on his temperament. It could be irritation or sadness. Often such people prefer to stay at home for a long time and spoil relationships with friends and family.

- Another characteristic symptom is apathy. A person only wants to be left alone. When the need to do something arises, it only spoils the mood and causes disgust. Being depressed, it seems to a person that the world around him has become gray and unfriendly. He does not want to do anything, since everything seems meaningless to him.

- Slow thinking. During depression, a person’s thinking slows down, even speech becomes sluggish. Because of this, he begins to have problems at work, since it becomes more difficult to fulfill his immediate responsibilities. Such a person actually sinks: he stops taking care of himself, cleaning the house, and going shopping.

- Physical features. Due to recurrent depressive disorder, appetite disappears and constant headaches occur. This leads to decreased performance, sexual and muscle activity. Possible difficulties with digestion, arrhythmia, increased sweating. Pain occurs in the abdomen and chest.

One of the most serious consequences of this disorder is a radical change in worldview. A person constantly feels self-doubt, his self-esteem falls. You have to live with a feeling of constant fear, anxiety and guilt.

To cope with the consequences of this situation, you need to seek help from specialists as soon as possible. You will not be able to find a way out of this situation on your own. Psychologist Nikita Valeryevich Baturin has proven methods of helping his clients.

Kinds

To determine treatment tactics, it is important to establish the severity of the developed disease. Episodes may also differ in the severity of symptoms. Transformation into other types of depressive disorders, for example, bipolar affective disorder (BAD), is not excluded.

Lightweight

To confirm a mild variant, the appearance of 2 main and additional symptoms of the episode is necessary. People with such recurrent depression are able to maintain social functioning. However, the quality of life still decreases. Somatic manifestations may be absent.

Moderate

With moderate recurrent depression, performing everyday tasks becomes almost impossible. A person cannot normally analyze information, study or work. Interpersonal relationships among family, friends, and loved ones suffer. For diagnosis, 2 main and 3-4 additional symptoms are enough.

Heavy

A severe depressive episode dramatically disrupts the social well-being of the patient. He loses the ability to perform not only work, but also household duties. There is a critical loss of interest in what is happening, nothing brings joy.

In this case, all the main symptoms, as well as 4 or more additional ones, are observed. Some episodes are aggravated by psychotic symptoms - delusions, hallucinosis, movement disorders or stupor. Increased risk of suicidal behavior.

Depressive disorders are the second leading medical cause of disability and mortality. WHO (World Health Organization) calls for combating the problem at the international level, having adopted a special resolution in 2013.

Literature

- A. S. Tiganov, A. V. Snezhnevsky, D. D. Orlovskaya, etc.

Guide to psychiatry in 2 volumes / Ed. Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences A. S. Tiganov. - M.: "Medicine", 1999. - T. 1. - 712 p. — ISBN 5-225-02676-1.

In the Brockhaus-Efron encyclopedic dictionary

- Melancholy // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Taedium vitae // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.