Authors: Mukhin K.Yu., Petrukhin A.S.

Part 1:

- Introduction

- Definition, classification of epilepsy

- Idiopathic generalized epilepsy

- Pediatric absence epilepsy.

- Juvenile absence epilepsy.

- Epilepsy with isolated generalized seizures.

- Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

- Idiopathic partial epilepsy

- Rolandic

- Idiopathic partial epilepsy with occipital paroxysms.

Part 2:

- Cryptogenic generalized epilepsy

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

- Epilepsy with myoclonic-astatic seizures.

- Epilepsy with myoclonic absence seizures

- Symptomatic partial epilepsy

- Symptomatic temporal lobe epilepsy

- Symptomatic frontal lobe epilepsy

- General principles of treatment of epilepsy

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

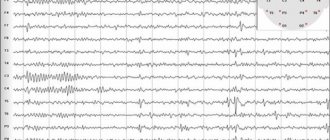

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is an epileptic encephalopathy of childhood, characterized by polymorphism of seizures, specific EEG changes and resistance to therapy. The frequency of LGS is 3-5% among all epileptic syndromes in children and adolescents; Boys get sick more often. The disease debuts mainly at the age of 2-8 years (usually 4-6 years). If LGS develops during transformation from West syndrome, then 2 options are possible: Infantile spasms transform into tonic seizures in the absence of a latent period and smoothly transform into LGS. Infantile spasms disappear; the child’s psychomotor development improves somewhat; the EEG picture gradually normalizes. Then, after a certain latent period of time, which varies in different patients, attacks of sudden falls, atypical absences appear, and diffuse slow peak-wave activity on the EEG increases. LSH is characterized by a triad of attacks: paroxysms of falls (atonic- and myoclonic-astatic); tonic seizures and atypical absence seizures. The most typical attacks are sudden falls caused by tonic, myoclonic or atonic (negative myoclonus) paroxysms. Consciousness can be maintained or switched off briefly. After the fall, no convulsions are observed, and the child gets up immediately. Frequent attacks of falls lead to severe trauma and disability of patients. Tonic seizures can be axial, proximal or total; symmetrical or clearly lateralized. Attacks include sudden flexion of the neck and torso, raising the arms in a state of semiflexion or extension, straightening the legs, contraction of the facial muscles, rotational movements of the eyeballs, apnea, and facial flushing. They can occur both during the daytime and, especially often, at night. Atypical absence seizures are also characteristic of LGS. Their manifestations are diverse. The impairment of consciousness is incomplete. Some degree of motor and speech activity may remain. Hypomimia and drooling are observed; myoclonus of the eyelids, mouth; atonic phenomena (the head falls on the chest, the mouth is slightly open). Atypical absence seizures are usually accompanied by a decrease in muscle tone, which causes the body to “go limp,” starting with the muscles of the face and neck. The neurological status shows manifestations of pyramidal insufficiency and coordination disorders. A decrease in intelligence is characteristic, but does not reach a severe degree. Intellectual deficit is detected from an early age, preceding the disease (symptomatic forms) or develops immediately after the onset of attacks (cryptogenic forms). An EEG study in a large percentage of cases reveals irregular diffuse, often with amplitude asymmetry, slow peak-wave activity with a frequency of 1.5-2.5 Hz during wakefulness and fast rhythmic discharges with a frequency of about 10 Hz during sleep. Neuroimaging may reveal various structural abnormalities in the cerebral cortex, including developmental defects: hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, hemimegalencephaly, cortical dysplasia, etc. In the treatment of LGS, drugs that suppress cognitive functions (barbiturates) should be avoided. The most commonly used drugs for LSH are valproate, carbamazepine, benzodiazepines, and lamictal. Treatment begins with valproic acid derivatives, gradually increasing them to the maximum tolerated dose (70-100 mg/kg/day and above). Carbamazepine is effective for tonic seizures - 15-30 mg/kg/day, but can increase absence seizures and myoclonic paroxysms. A number of patients respond to an increase in the dose of carbamazepine with a paradoxical increase in attacks. Benzodiazepines are effective for all types of seizures, but the effect is temporary. In the group of benzodiazepines, clonazepam, clobazam (Frisium) and nitrazepam (radedorm) are used. For atypical absence seizures, suxilep may be effective (but not as monotherapy). The combination of valproate with lamictal (2-5 mg/kg/day and higher) has been shown to be highly effective. In the United States, the combination of valproate and felbamate (thalox) is widely used.

The prognosis for LGS is severe. Stable control of attacks is achieved only in 10-20% of patients. The predominance of myoclonic seizures and the absence of gross structural changes in the brain are prognostically favorable; negative factors are the dominance of tonic seizures and gross intellectual deficit.

Forecast

Simple forms of myoclonus occur in normal, healthy people and do not cause serious problems. In some cases, the disorder begins in one area of the body and spreads to muscles in other areas. More severe cases of myoclonus can distort movement and severely limit a person's ability to eat, speak, or walk. These types of myoclonus may indicate a brain or nerve disorder.

Although clonazepam and sodium valproate are effective in treating most cases of the disorder, some people experience adverse reactions to these drugs. Additionally, the benefits of clonazepam may decrease with long-term use.

Epilepsy with myoclonic-astatic seizures.

Myoclonic-astatic epilepsy (MAE) is one of the forms of cryptogenic generalized epilepsy, characterized mainly by myoclonic and myoclonic-astatic seizures with onset in preschool age. The debut of MAE varies from 10 months. up to 5 years, averaging 2.3 years. In 80% of cases, the onset of attacks occurs within the age range of 1-3 years. In the vast majority of patients, the disease begins with GSP, followed by the addition of myoclonic and myoclonic-astatic seizures at the age of about 4 years. Clinical manifestations of MAE are polymorphic and include various types of seizures: myoclonic, myoclonic-astatic, typical absences, DBS with the possibility of partial paroxysms. The “core” of MAE are myoclonic and myoclonic-astatic seizures: short, lightning-fast twitches of small amplitude in the legs and arms; “nods” with slight propulsion of the body; “kicks to the knees.” The frequency of myoclonic attacks is high, especially in the morning after patients awaken. GSP is observed in almost all patients, absence seizures – in half. The addition of partial seizures is possible in 20% of cases. An EEG study is characterized by a slowdown in the main activity of the background recording with the appearance of generalized peak and polypeak wave activity with a frequency of 3 Hz. In most patients, regional changes are also observed: peak-wave and slow-wave activity. Treatment begins with monotherapy with valproic acid. Average doses are 50-70 mg/kg/day with a gradual increase to 100 mg/kg/day if there is no effect. In most cases, only polytherapy is effective: a combination of valproate with lamotrigine or benzodiazepines or succinimides. Seizure control is achieved in most patients, however, complete remission is possible only in 1/3 of cases. The addition of partial paroxysms significantly worsens the prognosis; These attacks are the most resistant to therapy. Transformation of MAE into Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is possible.

Clinical picture

The first manifestations of this disease can be diagnosed before the child reaches nine years of age. However, its debut occurs in adolescence, which may be associated with ongoing hormonal changes.

The first manifestations of the disease are periodically occurring short-term asynchronous attacks of tonic muscle contractions. In most cases, attacks occur in the morning, immediately after waking up. Muscle cramps are localized in the upper extremities, however, quite rarely they can migrate to the lower extremities and body.

During an attack, fine motor skills may be impaired, due to which the patient loses the ability to carry out complexly coordinated movements, and if attacks are localized in the lower extremities, gait disturbance or a complete inability to move independently may be observed. Myoclonic epilepsy can be either single or cluster in nature.

In less than 5% of cases, juvenile epilepsy can occur with only myoclonic seizures. However, almost always after the manifestation of myoclonic paradigms, the course of the disease is complicated by the appearance of generalized tonic-clinical epileptic seizures. In addition, approximately half of the patients eventually experience absence seizures - short-term loss of consciousness.

Epilepsy with myoclonic absence seizures.

Epilepsy with myoclonic absence seizures (EMA) is a form of absence epilepsy characterized by frequent absence seizures accompanied by massive myoclonus of the muscles of the shoulder girdle and arms, and resistance to therapy. The onset of attacks in UAE varies from 1 to 7 years (on average, 4 years); Boys predominate by gender. Myoclonic absence seizures are the first type of seizure in most patients. In some cases, the disease may begin with GSP followed by absence seizures. Complex absence seizures with a massive myoclonic component constitute the “core” of the clinical picture of UAE. Absence seizures are typical with intense myoclonic twitching of the shoulder girdle, shoulders and arms, usually of a bilaterally synchronous and symmetrical nature. In this case, a slight tilt of the torso and head anteriorly (propulsion), abduction and elevation of the shoulders (tonic component) may be observed. Most patients also experience myoclonic jerks of the neck muscles (short serial nods), synchronous with jerks of the shoulders and arms. A high frequency of absence seizures is characteristic, reaching 10 attacks per hour or more. The duration of the attacks ranges from 5 to 30 seconds, and long absence seizures are typical - more than 10 seconds. Attacks often become more frequent in the morning. The main factor provoking the occurrence of absence seizures in UAE is hyperventilation. In most cases (80%), absence seizures are combined with generalized convulsive seizures. A rare frequency of GSP is characteristic, usually not exceeding 1 time per month. EEG changes in the interictal period are detected in almost all cases. Slowing of the main background recording activity is observed infrequently, mainly in patients with intellectual deficits. A typical EEG pattern is a generalized spike (or, less commonly, polyspike) wave activity with a frequency of 3 Hz. Reliable for establishing the diagnosis of EMA is the appearance of discharges during electromyography in response to myoclonic muscle contractions that occur synchronously with peak-wave activity on the EEG (polygraphic recording). Treatment. Initial treatment is carried out with monotherapy with drugs derived from valproic acid. The average dosage is 50-70 mg/kg/day; if well tolerated, gradually increase to 80-100 mg/kg/day. In most cases, monotherapy reduces attacks, but does not lead to sufficient control over them. In this case, it is recommended to combine valproate with succinimides or lamotrigine.

In almost all patients, when using polytherapy in adequately high dosages, it is possible to achieve good control over attacks, however, remission occurs only in 1/3 of cases. Most patients have serious problems with social adaptation.

What is myoclonus?

Myoclonus (or myoclonus) is a symptom, not a disease, characterized by short-term rapid contractions of a muscle or group of muscles.

Myoclonic jerks or jerks are usually caused by sudden muscle contractions, called positive myoclonus, or muscle relaxations, called negative myoclonus. Myoclonic jerks can occur singly or sequentially, with or without a pattern. They may occur infrequently or multiple times every minute. Myoclonus sometimes occurs in response to an external event or when a person attempts to make a movement. The person experiencing the twitching cannot control it.

In its simplest form, myoclonus consists of muscle twitching followed by relaxation. An example is hiccups, which is also myoclonus. Other familiar examples of the condition are the jerks that some people experience while falling asleep. These simple forms of myoclonus occur in normal, healthy people and are not problematic. If more widespread, the condition can cause persistent shock-like contractions in a muscle group.

In some cases, myoclonus begins in one area of the body and spreads to muscles in other areas. More severe cases of the condition can distort movement and severely limit a person's ability to eat, speak, or walk. These types of myoclonus may indicate an underlying brain or nerve disorder.

The diagnosis is made based on symptoms and is sometimes confirmed by the results of an electromyographic study. Treatment includes correction of reversible diseases of the brain or nervous system and symptomatic therapy with medications.

Symptomatic partial epilepsy

In symptomatic partial forms of epilepsy, structural changes in the cerebral cortex are detected. The reasons that determine their development are diverse and can be represented by two main groups: perinatal and postnatal factors. A history of verified perinatal CNS damage is found in 35% of patients (intrauterine infections, hypoxia, ectomesodermal dysplasia, cortical dysplasia, birth trauma, etc.). Among postnatal factors, neuroinfections, traumatic brain injuries, and tumors of the cerebral cortex should be noted. The onset of seizures in symptomatic partial epilepsy varies over a wide age range, with a maximum in preschool age. These cases are characterized by changes in the neurological status, often in combination with a decrease in intelligence; the appearance of regional patterns on the EEG, resistance of attacks to AEDs and the possibility of surgical treatment. There are symptomatic partial forms of epilepsy: temporal, frontal, parietal and occipital. The first two are the most common and account for up to 80% of all cases.

Symptoms of myoclonus

Myoclonus may be mild or severe. Muscles can contract quickly or slowly, rhythmically or irregularly. Myoclonic jerks may be infrequent or frequent. They can occur spontaneously or under the influence of sudden noise, light or movement. For example, they can be triggered by reaching for an object or taking a step. In Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (a rare degenerative brain disease), myoclonus worsens with sudden fear.

Myoclonus, which develops as a result of metabolic disorders, can be long-lasting and affect different muscle groups, sometimes leading to cramps.

Symptomatic temporal lobe epilepsy.

The clinical manifestations of symptomatic temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) are extremely varied. In some cases, atypical febrile seizures precede the development of the disease. VE manifests itself as simple, complex partial, secondary generalized seizures, or a combination thereof. Particularly characteristic is the presence of complex partial seizures occurring with a disorder of consciousness, combined with preserved but automated motor activity. Automatisms in complex partial seizures can be unilateral, occurring on the side homolateral to the lesion, and are often combined with dystonic placement of the hand on the contralateral side. TE is divided into amygdala-hippocampal (paleocortical) and lateral (neocortical) epilepsy. Amygdala-hippocampal TLE is characterized by the occurrence of attacks with an isolated disorder of consciousness. Patients are observed to freeze with a mask-like face, wide-open eyes and gaze fixed at one point (he seems to be “staring” - “staring” in English literature). In this case, various vegetative phenomena may be observed: paleness of the face, dilated pupils, sweating, tachycardia. There are 3 types of SSP with an isolated disorder of consciousness: 1. Switching off consciousness with freezing and sudden interruption of motor and mental activity. 2. Turning off consciousness without interrupting motor activity. 3. Switching off consciousness with a slow fall (“limp”) without convulsions (“temporal syncopation”). Vegetative-visceral paroxysms are also characteristic. The attacks are manifested by a feeling of abdominal discomfort, pain in the navel or epigastrium, rumbling in the abdomen, the urge to defecate, and the passage of gas (epigastric attacks). An “ascending epileptic sensation” may appear, described by patients as pain, heartburn, nausea, emanating from the abdomen and rising to the throat, with a feeling of constriction, compression of the neck, a lump in the throat, often followed by loss of consciousness and convulsions. When the amygdala complex is involved in the process, attacks of fear, panic or rage occur; irritation of the hook causes olfactory hallucinations. Possible attacks with mental dysfunction (dreaming states, already seen or never seen, etc.). Lateral VE is manifested by attacks with impaired hearing, vision and speech. The appearance of bright colored structural (as opposed to occipital epilepsy) visual hallucinations, as well as complex auditory hallucinations, is characteristic. About 1/3 of women suffering from VE note an increase in attacks during the perimenstrual period. During a neurological examination of children suffering from VE, microfocal symptoms are often detected, contralateral to the lesion: insufficiency of the function of the 7th and 12th pairs of cranial nerves according to the central type, revival of tendon reflexes, the appearance of pathological reflexes, mild coordination disorders, etc. With age, most patients develop persistent disorders mental disorders, manifested mainly by intellectual-mnestic or emotional-personal disorders; The appearance of severe memory disorders is characteristic. The preservation of intelligence depends mainly on the nature of structural changes in the brain. An EEG study reveals peak-wave or, more often, persistent regional slow-wave (theta) activity in the temporal leads, usually extending anteriorly. In 70% of patients, a pronounced slowdown in the main activity of background recording is detected. In most patients, over time, epileptic activity occurs bitemporally. To identify a lesion localized in the medio-basal regions, the use of invasive sphenoidal electrodes is preferable. Neuroradiological examination reveals various macrostructural abnormalities in the brain. A common finding on MRI is medial temporal (incisural) sclerosis. Often there is also a local widening of the grooves, a decrease in the volume of the involved temporal lobe, and partial ventriculomegaly. Treating EV is challenging; many patients are resistant to therapy. Basic drugs are carbamazepine derivatives. The average daily dosage is 20 mg/kg. If ineffective, increase the dose to 30-35 mg/kg/day and higher until a positive effect or the first signs of intoxication appear. If there is no effect, you should abandon the use of carbamazepine, prescribing instead diphenin for complex partial seizures or valproate for secondary generalized paroxysms. The dosage of diphenine per day in the treatment of VE is 8-15 mg/kg, valproate – 50-100 mg/kg/day. If there is no effect from monotherapy, it is possible to use polytherapy: finlepsin + depakine, finlepsin + phenobarbital, finlepsin + lamictal, phenobarbital + diphenine (the latter combination causes a significant decrease in attention and memory, especially in children). In addition to basic anticonvulsant therapy, sex hormones can be used in women, which are especially effective for menstrual epilepsy. Oxyprogesterone capronate 12.5% solution 1-2 ml intramuscularly is used once on days 20-22 of the menstrual cycle. The prognosis depends on the nature of the structural damage to the brain. With age, most patients develop persistent mental disorders that significantly complicate social adaptation. In general, about 30% of patients suffering from TLE are resistant to traditional anticonvulsant therapy and are candidates for neurosurgical intervention.

Treatment of myoclonus

Treatment for myoclonus focuses on medications that can help reduce symptoms. The first choice drug for treatment, especially of certain types of myoclonus, is clonazepam, a type of tranquilizer. Dosages of clonazepam are usually increased gradually until the patient feels improvement or side effects appear. Drowsiness and loss of coordination are common side effects. The beneficial effects of clonazepam may decrease over time if a person develops tolerance to the drug.

Many medications used to treat myoclonus, such as barbiturates, levetiracetam, phenytoin, and primidone, are also used to treat epilepsy. Barbiturates slow down the central nervous system and cause a tranquilizing or antiseptic effect. Phenytoin, levetiracetam, and primidone are effective antiepileptic drugs, although phenytoin may cause liver failure or other harmful long-term effects. Sodium valproate is an alternative therapy for myoclonus and can be used alone or in combination with clonazepam. Although clonazepam and/or sodium valproate are effective for most people with the disorder, some people experience adverse reactions to these drugs.

Symptomatic frontal lobe epilepsy.

The clinical symptoms of frontal lobe epilepsy (FE) are varied. The disease manifests itself in simple and complex partial seizures, as well as, most characteristically, secondary generalized paroxysms. The following forms of LE are distinguished: motor, opercular, dorsolateral, orbitofrontal, anterior frontopolar, cingulate, emanating from the supplementary motor area. Motor paroxysms occur when the anterior central gyrus is irritated. Characteristic are Jacksonian seizures that develop contralateral to the lesion. Convulsions are predominantly clonic in nature and can spread like an ascending (leg - arm - face) or descending (face - arm - leg) march; in some cases with secondary generalization. With a focus in the paracentral lobules, seizures can be observed in the ipsilateral limb or bilaterally. Post-ictal limb weakness (Todd's palsy) is a common phenomenon of LE. Opercular seizures occur when the opercular zone of the inferior frontal gyrus at the junction with the temporal lobe is irritated. Manifested by paroxysms of chewing, sucking, swallowing movements, smacking, licking, coughing; hypersalivation is characteristic. There may be ipsilateral facial twitching, speech disturbances, or involuntary vocalizations. Dorsolateral seizures occur when the superior and inferior frontal gyri are stimulated. They manifest themselves as adverse attacks with forced rotation of the head and eyes, usually contralateral to the source of irritation. When the posterior parts of the inferior frontal gyrus (Broca's center) are involved, paroxysms of motor aphasia are detected. Orbitofrontal seizures occur when the orbital cortex of the inferior frontal gyrus is irritated and are manifested by a variety of autonomic-visceral phenomena. Characterized by epigastric, cardiovascular (pain in the heart, changes in heart rate, blood pressure), respiratory (inspiratory shortness of breath, feeling of suffocation, compression in the neck, “coma” in the throat) attacks. Pharyngo-oral automatisms with hypersalivation often appear. Noteworthy is the abundance of vegetative phenomena in the structure of attacks: hyperhidrosis, pale skin, often with facial hyperemia, impaired thermoregulation, etc. The appearance of typical complex partial (psychomotor) paroxysms with automatisms of gestures is possible.

Anterior (frontopolar) seizures occur when the poles of the frontal lobes are irritated. They are characterized by simple partial seizures with impaired mental functions. They manifest themselves as a feeling of sudden “failure of thoughts,” “emptiness in the head,” confusion, or, conversely, a violent memory; a painful, painful feeling of the need to remember something. A violent “influx of thoughts”, a “whirlwind of ideas” is possible - a feeling of a sudden appearance in the mind of thoughts that are not related in content to the current mental activity. The patient does not have the opportunity to get rid of these thoughts until the end of the attack. Cingular seizures originate from the anterior cingulate cortex of the medial frontal lobes. They manifest themselves mainly as complex, less often simple partial seizures with behavioral and emotional disturbances. Characterized by complex partial seizures with automatisms of gestures, facial flushing, fearful expression, ipsilateral blinking movements, and sometimes clonic convulsions of the contralateral limbs. Paroxysmal dysphoric episodes with anger, aggressiveness, and psychomotor agitation may occur. Seizures emanating from the supplementary motor area were first described by Penfield, but were systematized only recently. This is a fairly common type of attack, especially considering that paroxysms that occur in other parts of the frontal lobe often radiate to the supplementary motor area. Characterized by the presence of frequent, usually nocturnal, simple partial attacks with alternating hemiconvulsions and archaic movements; attacks with cessation of speech, unclear, poorly localized sensory sensations in the trunk and limbs. Partial motor seizures usually manifest themselves as tonic convulsions, occurring either on one side or the other, or bilaterally (at the same time they look like generalized ones). Characteristic is tonic tension with raising of the contralateral arm, adversion of the head and eyes (the patient seems to be looking at his raised arm). The occurrence of “inhibitory” attacks with paroxysmal hemiparesis has been described. Attacks of archaic movements usually occur at night with high frequency (up to 3-10 times per night, often every night). They are characterized by a sudden awakening of patients, screaming, a grimace of horror, a motor storm: waving arms and legs, boxing, pedaling (reminiscent of riding a bicycle), pelvic movements (as during coitus), etc. The degree of disturbance of consciousness fluctuates, but in most cases consciousness is preserved. These attacks should be differentiated from hysterical and paroxysmal night terrors in children. An EEG study for LE may show the following results: normal, peak-wave activity or slowing (periodic rhythmic or continuous) regionally in the frontal, fronto-central or frontotemporal leads; bifrontal independent peak-wave foci; secondary bilateral synchronization; regional frontal low-amplitude fast (betta) activity. Lesions localized in the orbitofrontal, opercular and supplementary motor areas may not show changes when applying surface electrodes and require the use of depth electrodes or corticography. When the supplementary motor area is damaged, EEG patterns are often ipsilateral to seizures or bilateral, or the phenomenon of secondary bilateral Jasper synchronization occurs. Treatment of LE is carried out according to the general principles of treatment of localization-related forms of epilepsy. Carbamazepine (20-30 mg/kg/day) and valproate (50-100 mg/kg/day) are the drugs of choice; diphenine, barbiturates and lamotrigine are reserved. Valproate is especially effective in cases of secondary generalized seizures. If monotherapy is ineffective, polytherapy is used - a combination of the drugs listed above. Complete resistance of attacks to AED therapy is a reason to consider surgical intervention. The prognosis of PE depends on the nature of the structural damage to the brain. Frequent attacks, resistant to therapy, significantly worsen the social adaptation of patients. Seizures originating from the supplementary motor area are usually resistant to traditional AEDs and require surgical treatment.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made on the basis of a combination in a wedge, a picture of myoclonic hyperkinesis with epileptic seizures. The family nature of the disease is important for diagnosis. The differential diagnosis is made with a very similar cerebellar myoclonic dyssynergia of Hunt - a hereditary, autosomal recessive disease, in which myoclonic hyperkinesis and epileptic seizures are also observed, but, unlike M.-e., cerebellar disorders are much more pronounced. Unlike M.-e., with Kozhevnikov epilepsy (see), clonic convulsions are observed in a certain part of the body and are usually not of a generalized nature. It is especially difficult to establish an early diagnosis in sporadic cases when the disease manifests itself as an incomplete wedge, syndrome - either epileptic seizures or myoclonic hyperkinesis. In this case, family history is important, as well as a decrease in the content of mucopolysaccharides in the blood serum.

General principles of treatment of epilepsy

Currently, generally accepted international standards for the treatment of epilepsy have been developed, which must be observed to increase the effectiveness of treatment and improve the quality of life of patients.

Treatment for epilepsy can only begin after an accurate diagnosis has been established. The terms “pre-epilepsy” and “preventive treatment of epilepsy” are absurd. There are two categories of paroxysmal neurological disorders: epileptic and non-epileptic (fainting, sleepwalking, night terrors, etc.), and the prescription of AEDs is justified only in case of illness. According to most neurologists, treatment for epilepsy should begin after a recurrent attack. A single paroxysm can be “random”, caused by fever, overheating, intoxication, metabolic disorders and not related to epilepsy. In this case, the immediate prescription of AEDs cannot be justified, since these drugs are potentially highly toxic and are not used for the purpose of “prevention”. Thus, AEDs can only be used in cases of recurrent, unprovoked epileptic seizures (i.e., epilepsy by definition).

If an accurate diagnosis of epilepsy is established, it is necessary to decide whether AEDs should be prescribed or not? Of course, in the vast majority of cases, AEDs are prescribed immediately after epilepsy is diagnosed. However, with some benign epileptic syndromes of childhood (primarily with rolandic epilepsy) and reflex forms of the disease (reading epilepsy, primary photosensitivity, etc.), it is possible to manage patients without the use of AEDs. Such cases must be strictly reasoned.

The diagnosis of epilepsy was established and it was decided to prescribe AEDs. Since the 1980s, the principle of monotherapy has been firmly established in clinical epileptology: the relief of epileptic seizures should be carried out primarily with one drug. With the advent of chromatographic methods for determining the level of AEDs in the blood, it became obvious that many anticonvulsants have mutual antagonism, and their simultaneous use can significantly weaken the anticonvulsant effect of each. In addition, the use of monotherapy avoids the occurrence of severe side effects and teratogenic effects, the frequency of which increases significantly when multiple drugs are prescribed simultaneously. Thus, the old concept of prescribing a large number of AEDs simultaneously in small doses has now been completely proven to be untenable. Polytherapy is justified only in the case of resistant forms of epilepsy and no more than 3 AEDs at a time.

The selection of AEDs should not be empirical. AEDs are prescribed strictly in accordance with the form of epilepsy and the nature of the attacks. The success of epilepsy treatment is largely determined by the accuracy of syndromic diagnosis (Table 3).

AEDs are prescribed starting with a low dose, with a gradual increase until therapeutic effectiveness is achieved or the first signs of side effects appear. In this case, the determining factor is the clinical effectiveness and tolerability of the drug, and not its content in the blood (Table 4).

If one drug is ineffective, it should be gradually replaced by another AED that is effective for this form of epilepsy. If one AED is ineffective, you cannot immediately add a second drug to it, that is, switch to polytherapy without using all the reserves of monotherapy.

Principles of AED withdrawal.

AEDs can be discontinued after 2.5-4 years of complete absence of attacks. The clinical criterion (absence of seizures) is the main criterion for discontinuation of therapy. In most idiopathic forms of epilepsy, drug withdrawal can be carried out after 2.5 (rolandic epilepsy) - 3 years of remission. In severe resistant forms (Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, symptomatic partial epilepsy), as well as in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, this period increases to 3-4 years. If complete therapeutic remission lasts for 4 years, treatment should be discontinued in all cases. The presence of pathological changes on the EEG or the puberty period of patients are not factors delaying the discontinuation of AEDs in the absence of attacks for more than 4 years. There is no consensus on the tactics of AED withdrawal. Treatment can be canceled gradually over 1-6 months or simultaneously at the discretion of the doctor.

part-1 part-2

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment is symptomatic. Anticonvulsant therapy is used, phenobarbital, benzonal, seduxen, chloral hydrate are prescribed. The last two remedies can significantly reduce myoclonic hyperkinesis for a short time. The use of chloral hydrate can cause addiction to it and the rapid development of cachexia. Repeated long-term courses of treatment with glutamine are also indicated.

The prognosis is unfavorable. Average duration of illness approx. 20 years, some patients live to old age. The most common cause of death is increasing cachexia, often pneumonia and other intercurrent diseases.

Spouses whose family has a patient with myoclonus epilepsy are advised to seek medical genetic consultation to resolve the issue of having a child (see).

Bibliography:

Davidenkov S.N. Myoclonus-epilepsy, in the book: Neurol. and genetics, ed. S. N. Davidenkova, vol. 2, p. 195, M., 1936; Dzerzhinsky V. Myoclonia Unverricht'a, Zhurn, neuropathist, and psychiatrist, book. 5-6, p. 293, 1910; McKusick V. A. Hereditary characteristics of man, trans. from English, M., 1976; Melnikov S.A. Myoclonus-epilepsy as a syndrome in certain diseases of the brain, Zhurn, neuropath, and psychiat., t. 57, century. 6, p. 740, 1957, bibliogr.; de Ajuriaguerra J., Sigwald J. et Piot C. Myoclonie-epilepsie familiare de type Unverricht, Presse med., p. 1813, 1954; Bogaert L. Sur l'epilepsie-myoclonie progressive d'Unverricht - Lundborg, Mschr. Psychiat. Neurol., Bd 118, S. 170, 1949, Bibliogr.; Davison Ch. a. Keshner M. Myoclonus epilepsy, Arch. Neurol. Psychiat. (Chic.), v. 43, p. 524, 1940; Gambetti P. ao Myoclonic epilepsy with lafora bodies, Arch. Neurol. (Chic.), v. 25, p. 483, 1971; Hallidau AM Les differents types des myoclonies, Rev. neurol., t. 119, p. 135, 1968; Handbook of clinical neurology, ed. by PJ Yinken a. G. W. Bruyn, v. 15, p. 121, 1974, v. 27, p. 171, Amsterdam ao, 1976; Lafora GR u. Glueck B. Beitrag zur Histopathologie der myoclonischen Epilepsie, Z. ges. Neurol. Psychiat., Bd 6, S. 1, 1911, Bibliogr.; LundborgH. Die progressive Myoclonus-Epilepsy, Upsala, 1903; Unverricht H. Die Myoclonie, L]3z.—Wien, 1891.

R. A. Tkachev.