general description

Arteriovenous malformation is a condition in which pathologically tortuous shunt vessels appear between arteries and veins instead of a network of capillaries. It can occur anywhere, but the most clinically significant is cerebral arteriovenous malformation. As a result of replacement of the capillary bed, the exchange of oxygen and nutrients between tissues and blood is disrupted, and the brain experiences oxygen starvation. In addition, vessels with arteriovenous malformation of the brain have a thinner wall than normal, so they can rupture. The risk of rupture reaches 4% per year. Mortality from AVM rupture in non-operated patients reaches 30%, disability – 50%.

Diagnostic methods

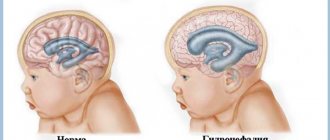

In case of severe anomalies, diagnosis can be made by visual examination. Indications for additional examination may include:

- Muscle hypotonia during the neonatal period;

- The appearance of convulsive syndrome;

- Impaired mental function.

Diagnostic methods are:

- Screening and obstetric ultrasound during pregnancy;

- Neurosonography through the fontanel in the first 1-1.5 years of life;

- EEG and EEG video monitoring make it possible to determine the presence of convulsive syndrome and select effective anticonvulsant therapy;

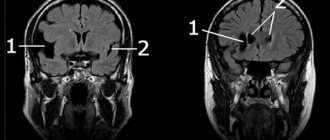

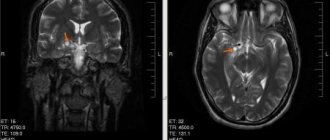

- Magnetic resonance imaging, which is the most informative method that allows you to visualize pathologies, their structure, shape, size and location.

To detect concomitant somatic defects, ultrasound of the kidneys, heart, and abdominal cavity is indicated. In addition, genetic counseling may be required.

Cerebral anomalies must be distinguished from fetal asphyxia or hypoxia and neonatal injuries.

Symptoms

Arteriovenous malformation can be asymptomatic, in which case the patient will never know that he had this pathology. In half of the diagnosed cases, the disease manifested itself with bleeding. Rupture of a deformed vessel threatens hemorrhagic stroke, disability and death. In another quarter of cases, the malformation causes epileptic seizures. Large and distended vessels can cause persistent and intractable headaches, and if their size is so large that it leads to compression of brain tissue, focal neurological deficits can occur.

Reasons for violations

Monogenic inheritance causes the anomaly in only 1% of cases. Most often, disruptions in intrauterine development are caused by a number of harmful teratogenic factors affecting the body of the mother and child. Exogenous factors include:

- Radioactive exposure;

- Exposure to chemicals;

- Heat;

- Action of high-frequency currents;

- Unfavorable environmental conditions, causing toxic substances to enter the pregnant woman’s body.

In addition, many medications and hormonal drugs that the mother takes in the early stages, without knowing about pregnancy, can be teratogenic. It has been proven that most pharmacological drugs easily cross the placental barrier, entering the child’s circulatory system. Even taking large doses of calcium supplements and vitamin complexes can be dangerous. Immune incompatibility between mother and child is unfavorable for the formation of a healthy fetus. Developmental defects can also be caused by dysmetabolic disorders, viral and intrauterine infections, including asymptomatic ones. Very dangerous:

- Hyperthyroidism;

- Diabetes;

- Metabolic pathologies;

- Syphilis;

- Cytomegaly;

- Rubella;

- Listeriosis;

- Toxoplasmosis.

The lifestyle of the pregnant woman has a huge impact on the successful course of pregnancy. Teratogenic effects are exerted by:

- Addiction;

- Alcoholism;

- Smoking.

Treatment of brain AVM

Treatment consists of surgical removal of pathological vessels. Classical open excision of a malformation is used mainly only in emergency cases, when a vessel ruptures, when it is necessary not only to remove it, but also to aspirate the resulting hematoma.

In case of uncomplicated malformation, one can resort to angioembolization, when an embolic substance is injected into the pathological vessel, its lumen is permanently closed and the vessel functionally disappears.

The most modern method is radiosurgery, during which the malformation is irradiated, leading to complete closure of the lumen of the vessel.

Vascular cognitive disorders

About the article

4396

0

Regular issues of "RMZh" No. 12 dated June 24, 2005 p. 789

Category: General articles

Authors: Yakhno N.N. 1, Zakharov V.V. 1 Research Institute of Neurology, Research Center Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education “First Moscow State Medical University named after. I. M. Sechenov" Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation

For quotation:

Yakhno N.N., Zakharov V.V. Vascular cognitive disorders. RMJ. 2005;12:789.

Cerebrovascular disorders are one of the most common pathological conditions in neurological practice. Cerebrovascular insufficiency naturally occurs with atherosclerosis of the main arteries of the head, hypertension, and other diseases of the cardiovascular system. It is important to note that in recent years there has been a tendency towards an increase in the incidence of cardiovascular disorders not only in old age, but also among middle-aged and young people. Pathology of cerebral vessels can lead to both repeated acute disorders of cerebral circulation and chronic cerebral ischemia. Often, repeated strokes and chronic ischemia coexist, and both of these pathogenetic factors eventually lead to the formation of the clinical syndrome of dyscirculatory encephalopathy (DE) [2].

A practicing neurologist is well aware of the clinical manifestations of DE. An important place among them is occupied by cognitive dysfunction. Cognitive impairment is probably the most common manifestation of cerebrovascular disease. Moreover, the severity of cognitive impairment can vary significantly depending on the stage of the process and the severity of the underlying vascular disease. Traditionally, the main object of interest of doctors and researchers has been vascular dementia, which is believed to be the second most common in the population after primary degenerative dementia. However, more attention is now being paid to less severe cognitive impairment. This reflects the general trend in modern neurogeriatrics towards maximum optimization of early diagnosis and treatment of cognitive impairment. In 1994, one of the world's most respected angioneurologists, V. Hachinski, proposed using the term “vascular cognitive impairment” (VCI) to refer to disorders of higher brain functions due to cerebrovascular pathology [34]. This concept unites both vascular dementia and less severe impairments of cognitive functions of vascular etiology. Vascular cognitive disorders (VCDs) have characteristic features of pathogenesis and clinical features, as well as courses that make it possible to differentiate this type of cognitive impairment from also very common cognitive impairments of a neurodegenerative nature. Mechanisms of occurrence of vascular cognitive disorders Cognitive impairments in cerebrovascular insufficiency develop as a result of repeated strokes, chronic cerebral ischemia, or a combination of both of these pathogenetic factors. It is customary to divide TFR into two main options: TFR for pathology of large vessels and TFR for pathology of small vessels. Pathology of large cerebral arteries (atherosclerosis, cardiogenic thromboembolism) is known to lead to large-focal cerebral infarctions of cortical localization. Since cognitive functions are provided by the integrative activity of the entire brain, cognitive impairment can occur with different localization of the ischemic focus. In this case, the nature of cognitive disorders will directly depend on the location of the cerebral infarction, and the severity will depend on its size. Thus, cognitive impairment in pathology of the large cerebral arteries represents a group of neuropsychological syndromes that is very heterogeneous in nature and severity [35]. More homogeneous in clinical picture are SCRs associated with pathology of small-caliber vessels. As you know, the most common cause of damage to small vessels is hypertension. The anatomical features of the blood supply to the brain are such that with uncontrolled arterial hypertension, the deep parts of the white matter of the brain and the subcortical basal ganglia are primarily affected. These parts of the brain are the “favorite” location for lacunar infarctions. A reflection of chronic cerebral ischemia are changes in the white matter (so-called leukoaraiosis), which are also noted primarily in the deep cerebral regions [6]. The basal ganglia are very important integrative formations for cognitive activity, through which the associative zones of the anterior and posterior parts of the cerebral cortex communicate with each other [47]. White matter damage also causes cognitive dysfunction because it leads to deafferentation of the frontal lobes of the brain (the so-called “disconnection phenomenon”). Thus, the predominant result of damage to the deep white and gray matter is secondary dysfunction of the anterior parts of the brain. It is assumed that dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain plays a key role in the formation of cognitive disorders in the pathology of small vessels [2,3,6,22,36]. Clinical features of vascular cognitive disorders As already noted, the clinical picture of SCD in the pathology of large vessels is very heterogeneous and is determined mainly by the localization of strokes. In contrast, TFR in arterial hypertension is quite uniform due to the above-mentioned anatomical features of the blood supply to the brain. Typical manifestations of SCR in pathology of small vessels are neuropsychological symptoms of frontal dysfunction. According to the theory of systemic dynamic localization of higher brain functions by A.R. Luria, the function of the frontal lobes of the brain is to program voluntary activity and control the implementation of the intended program [7]. One of the first symptoms of frontal dysfunction in SRS is often slower thinking: patients take more time and effort to perform various mental exercises, and find it difficult to concentrate. Violations of voluntary attention are characteristic: patients experience difficulty switching from one stage of activity to another, or, on the contrary, are distracted from the intended program. The consequences of these disorders are perseveration and increased impulsivity. Violation of analytical abilities is also characteristic. For example, patients with IBS will have difficulty generalizing concepts or trying to explain the meaning of proverbs and sayings [1–3,12,15,22]. The basal ganglia are an important sensory relay and are involved in the formation of spatial representations [10,48]. Damage to these anatomical formations can lead to visual-spatial disorders. The simplest test for diagnosing this type of disorder is a clock drawing test: the patient is asked to independently draw a round clock with numbers on the dial and place the hands at a certain time indicated by the doctor. Impaired memory for current events is not typical for SCD. The presence of such disorders almost always indicates the presence of a concomitant neurodegenerative process. However, with SCS, working memory impairments may develop. At the same time, it is difficult for patients to retain large amounts of information and quickly switch from one source of information to another. Impairments in working memory significantly complicate the processes of learning and acquiring new skills, but, as mentioned above, do not extend to memorizing and reproducing life events [13]. Cognitive impairment in SCD is almost always combined with emotional and behavioral disorders, since the latter are also based on secondary dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain. It is well known that mild depression is often observed in the very early stages of cerebrovascular insufficiency. It is this type of emotional disturbance that underlies nonspecific complaints of headache, heaviness in the head, non-systemic dizziness, and increased fatigue, which regularly occur at stage I of dyscirculatory encephalopathy. More pronounced disorders may be accompanied by emotional lability, decreased motivation and initiative, decreased criticism, and inappropriate behavior [2,11]. Cognitive impairment in cerebrovascular insufficiency varies greatly in severity. The most severe disorders that cause professional and everyday maladaptation of the patient are usually referred to as vascular dementia. Less severe impairments, which, nevertheless, go beyond the age norm and are noticeable to others, according to modern concepts are called moderate cognitive impairment (MCI). The criteria developed by the Mayo Clinic Memory Laboratory are currently used to diagnose MCI (Table 1) [46]. A study conducted in our clinic showed that among patients with stage I and II DE syndrome, cognitive impairment met the accepted diagnostic criteria for MCI in 56% of cases. The remaining patients, according to our data, were also not cognitively perfect. In another 32%, detailed neuropsychological examination revealed slight difficulties in performing certain tests, mainly as a result of slowness and impaired concentration. These cognitive symptoms were not noticeable to others, but often caused subjective anxiety. Thus, in our opinion, along with the syndrome of moderate cognitive impairment, it is advisable to distinguish the syndrome of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In MCI, disorders are invisible to others, but are felt by the patient himself and are confirmed by careful examination using sensitive techniques [16]. The relationship between SCD and the neurodegenerative process According to epidemiological data, cerebrovascular disorders are the second most common cause of cognitive failure in old age, second only to Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, recently, an increasing number of studies indicate a significant prevalence of mixed forms, when the same patient exhibits signs of both degenerative and vascular lesions of the brain. Thus, according to American clinical and morphological comparisons, lacunar infarctions and leukoaraiosis are detected at autopsy in 48% of patients with BA. On the other hand, in 77% of patients with a clinical diagnosis of vascular dementia, morphological examination reveals signs of a degenerative process in the form of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [20,30,39,43]. The reasons for such frequent coexistence of the most common etiological forms of cognitive impairment are widely discussed. One of the reasons is quite obvious: both asthma and cerebrovascular disorders are diseases of old age. The simultaneous presence of several chronic diseases in an elderly person, of course, is not something exceptional. However, the actual prevalence of mixed vascular-degenerative cognitive disorders significantly exceeds the expected prevalence if the two diseases coincide by chance. A number of studies have shown that hypoxia due to chronic cerebral ischemia increases the risk of genetic predisposition to AD and accelerates the rate of progression of the neurodegenerative process. At the same time, the structures of the hippocampal circle are especially sensitive to ischemia and hypoxia, in which the most pronounced pathomorphological changes are detected in AD. On the other hand, the key event in the pathogenesis of AD is the formation of a pathological protein - b-amyloid, which is deposited both in the brain parenchyma and in the cerebral vessels [3,8,9,41]. The presence of concomitant cerebrovascular disorders has a significant impact on the clinical manifestations of asthma. Thus, in the work of E.O. Mkhitaryan showed that in elderly patients with AD and significant cerebrovascular insufficiency, even with mild dementia, neuropsychological symptoms of frontal dysfunction are detected. It is known that in “pure” AD, the anterior parts of the frontal lobes are involved in the pathological process only in the late stages of the disease [8]. On the other hand, according to our data, some patients with stage I and II DE and MCI syndrome exhibit neuropsychological signs of the initial stages of AD. Thus, in 23% of the 56% of patients with DE and MCI we observed, along with the typical clinical manifestations of SCD, primary impairments in memory and nominative speech function, characteristic of the neurodegenerative process, were determined. In these cases, in our opinion, a mixed, vascular-degenerative nature of cognitive impairment is very likely. In the remaining patients with DE and MCI, cognitive impairment was characterized mainly by neuropsychological symptoms of frontal dysfunction, which may indicate their predominantly vascular etiology [16]. Thus, identifying the clinical features of cognitive impairment is important for determining the etiology of the impairment. Insufficient memory for current events and impairment of the nominative function of speech reflect the involvement of the hippocampus and left temporal lobe, which is characteristic of the neurodegenerative process within AD. Neuropsychological symptoms of frontal dysfunction with mild to moderate cognitive impairment are more characteristic of SCD. In clinical practice, a combination of primary memory impairment and frontal dysfunction is often observed. In such cases, it is natural to assume the coexistence of AD and SCR. At the same time, mild and moderate severity of cognitive impairment, slow progression or a relatively stationary state of cognitive impairment should not be considered as signs that exclude AD. It is known that when this disease begins in old age (after 65–70 years), it is often relatively benign in nature [3,41]. Diagnosis of SCD To objectify cognitive impairment, neuropsychological research methods are used. The generally accepted standard for screening for cognitive impairment is the Mini-Mental Status Scale (MSMS) [28]. However, it should be kept in mind that this technique was originally developed for diagnosing asthma. The tasks included in this scale assess memory, orientation, counting, speech and constructive praxis, that is, those cognitive functions that are most vulnerable in AD. Patients with SRS, even with significant severity of disorders, can receive a fairly high score on the KSHOPS. Therefore, if a vascular etiology of cognitive disorders is suspected, it is advisable to supplement the CSPS with neuropsychological tests that are sensitive to frontal dysfunction. A short battery of the simplest frontal tests with a formalized quantitative assessment of the results was proposed in 1999 by the French neurologist B. Dubois and has been successfully used in our clinic for several years (Table 2) [24]. In addition to the verification of cognitive impairment, for a valid diagnosis of SCS it is necessary to identify the underlying vascular disease. For this purpose, a full clinical and instrumental examination using neuroimaging methods is advisable: computer or (preferably) magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. However, it is important to emphasize that the mere establishment of the presence of cognitive impairment and cerebrovascular insufficiency does not mean a cause-and-effect relationship between the first and second. Arguments in favor of such a connection, according to most researchers, can be either temporary relationships (the occurrence of cognitive impairment in the first months after a stroke) or characteristic clinical features of cognitive impairment in the form of a predominance of symptoms of frontal dysfunction. Treatment of vascular cognitive disorders Therapeutic measures for CS should be aimed at the underlying vascular disease, as well as at improving microcirculation and cerebral metabolism. At the stage of vascular dementia, symptomatic neurotransmitter replacement therapy is also advisable. Treatment of the underlying disease. Brain damage leading to the formation of CS is always a complication of diseases of the cardiovascular system. Therefore, in the presence of TBS, a thorough assessment of the state of the cardiovascular system is mandatory. Antihypertensive drugs, antiplatelet agents and lipid-lowering agents should be used according to appropriate indications. Control of heart rate, diabetes mellitus, smoking cessation, control of excess weight and physical inactivity, and elimination of other correctable risk factors for cerebral ischemia are important. In cases of hemodynamically significant cerebral artery stenosis, vascular surgery techniques may be discussed. Vasoactive drugs. A necessary component of the pathogenetic therapy of SCC is the improvement of cerebral microcirculation. For this purpose, phosphodiesterase inhibitors (pentoxifylline, vinpocetine), calcium channel blockers (cinnarizine, flunarizine), a-blockers (nicergoline) and some other drugs are widely used. The drug Tanakan, a highly effective broad-spectrum cerebroprotector consisting of natural ingredients, has a very favorable profile of pharmacological activity. Tanakan has a versatile positive effect on cerebral blood flow without causing a “stealing” effect. This effect is achieved by normalizing the tone of the blood vessels in the affected area, and not by simply dilating them everywhere. By inhibiting platelet activating factor, Tanakan reduces the degree of aggregation of blood cells, thereby improving its rheological properties [19,33]. One of the most important qualities of Tanakan is the ability of the components of this drug to deactivate free radicals. The antioxidant properties of Tanakan were demonstrated in numerous experimental work [23,31,32,38,45]. Since the processes of lipid peroxidation play a very significant role in damage to neurons both with hypoxia and in neurodegenerative processes, the presence of antioxidant properties in the Tanakan allows the use of this drug for “pure” TFR and in cognitive impairment of mixed, vascular -deigenerative nature. The clinical efficiency of Tanakan was proved in a large series of double blind placebo -controlled studies. The drug has a positive nootropic effect in the form of improving memory, attention and other cognitive functions, contributes to the normalization of bioelectric activity of the brain both in patients with vascular cerebral failure and with a neurodegenerative process [5,29,37,40,42]. There are observations that a prolonged Tanakan intake reduces the risk of Alzheimer's disease, and in patients with this disease, it helps to reduce the rate of progression of cognitive disorders [17,21]. An important advantage of Tanakan is its good tolerance. It rarely has any side effects. The drug does not affect systemic hemodynamics and vital functions, does not have drug interaction with any other drugs. The drug is used in doses of 40–80 mg two to three times a day. Metabolic drugs. Metabolic drugs contribute to an increase in neuronal plasticity, that is, the properties of neurons to change their functional properties depending on the conditions of the environment. Neurometabolic therapy is of particular importance in the recovery period of ischemic stroke, cranial -brain injury or other acute central nervous system. Wide practical experience indicates the advisability of the use of metabolic drugs for cognitive disorders, especially mild and moderate severity [3]. Drugs with metabolic effects include piracetams and its derivatives. The metabolic effect is possessed by biologically active amino acids and polypetides, which are contained in drugs such as cerebrolysine, etc. Along with all the above properties, Tanakan also has a positive neurometabolic effect. Such a breadth of pharmacological action allows the use of tanakan in the form of monotherapy in young patients in the initial forms of DE and the associated cognitive disorders and in senile patients with polyorganic pathology in order to reduce the drug load and minimize the side effects of the therapy. Putting neurotransmitter therapy. At the stage of vascular dementia, the use of acetylcholinergic and glutamatergic drugs is pathogenetically justified. Currently, there are clinical evidence of the effectiveness of acetylcholinersterase inhibitors (galantamine, rivastigmin) and a NMDA memantine NMDA receptor with vascular and mixed dementia [18,25–27,44]. The use of these drugs at the stage of moderate cognitive disorders is discussed, but this issue requires further study. At the stage of mild cognitive disorders for symptomatic purposes, a dopaminergic drug Piribedil can be used, which, according to some sources, helps to reduce the severity of the neuropsychological symptoms of frontal dysfunction [4]. The conclusion in this way, the TFR are very common in the practice of neurological pathology. At the same time, the neuropsychological features of the identified disorders, reflecting their connection with the dysfunction of the frontal brain of the brain, will be evidenced of the vascular etiology of cognitive disorders. The presence, along with neuropsychological symptoms of frontal dysfunction of primary memory impairment, indicates in favor of mixed vascular -depth etiology of cognitive disorders. Therapy of the TFR, aimed both at the treatment of the underlying disease and the neurochemical mechanisms of cognitive impairment, helps to improve the quality of life of the patient and his relatives with any severity of the disorders. However, the greatest effect of therapy should be expected at its beginning at the stage of mild dementia or cognitive disorders that do not reach the stage of dementia. Literature 1. Damulin I.V., Yakhno N.N. Vascular cerebral failure in elderly and senile patients (clinical and computer -tomographic examination). // f neuropathology and psychiatry. –1993. –T.93. –N.2. —P. 10–13. 2. Damulin I.V. Discirculatory encephalopathy in elderly and senile age. // Author. Dros. honey. Sci. –M. –1997. –32 p. 3. Damulin I.V. Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. // Ed. N.N. Yakhno. –M., 2002. –85 p. 4. Zakharov V.V., Lokshina A.B. The use of the drug Prononran (Piribedil) for mild cognitive disorders in elderly patients with discirculatory encephalopathy. // Neurological journal. –2004. 5. Zakharov V.V. The use of tanakan in neuroheriatric practice. // Neurological journal. –1997. –T.5. —P.42–49. 6. Levin O.S., Damulin I.V. Diffuse changes in white matter (leulyaareosis) and the problem of vascular dementia. 7. Luria A.R. The highest cortical functions of a person. /M.: Publishing House of Moscow State University. –1969 8. Mkhitaryan 9. Preobrazhenskaya I.S., Mkhitaryan E.A., Yakhno N.N. The role of vascular disorders in the pathogenesis of degenerative dementia. // Fundamental Sciences and Progress of Clinical Medicine. Scientific and practical conference. –2002. –Teles of reports. —P.321. 10. Tolkunov B.F. STRIATUM and sensory specialization of the neural network. // Leningrad: Publishing House "Science". –1978. —P. 178. 11. Yanakaeva T.A. A comparative analysis of cognitive and affective disorders for discirculatory encephalopathy and Parkonon's disease. // Diss ... Cand. honey. Sci. -Moscow. –1999. 12. Yakhno N.N., Damulin I.V., Bibikov L.G. Chronic vascular brain deficiency in the elderly: clinical -computer -tomographic comparisons. // Clinical gerontology. –1995. –N.1. —P.32–36. 13. Yakhno N.N., Zakharov V.V. Memory disorders in neurological practice. //Neurologist. Journal. –1997. — No..4. –P.4–9. 14. Yakhno N.N., I.V. Damulin, V.V. Zakharov et al. The use of tanakan in the initial stages of vascular brain failure: the results of an open multicenter study. // Neurological journal. –1998. –T.3. —P. 18–22. 15. Yakhno N.N., Levin O.S., Damulin I.V. Comparison of clinical and MRI data for discirculatory encephalopathy. Message 2: Cognitive disorders. // Neurol. Zhurn. –2001. –T.6, No. 3. –P.10–19. 16. Yakhno N.N., Zakharov V.V., Lokshina A.B. Syndrome of mild cognitive impairment in dyscirculatory encephalopathy. // w neurol psychiatrist. –2005. –T.105. — No. 2. —P. 13–17. 17. Andrieu S., Amouyal K., Reinish W., Nourhashemi F., Vellas B., Albarede Jl, Granjean H. for Epidos Group. The Consumption of Vasodilators and Gingko Biloba (EGB 761) In A Population of 7598 Women Over the Age of 75 Years. // Research and Practice in Alzheimer's Disease. –2001. –V.5. –P.57–68. 18. Areosa Sa, Sheriff F. Memantine for Dementia (Cochrane Review). // The Cochrane Library. —Issue 1. Chichester: John Willey a Sons Ltd. –1004. 19. Auguet M., Fvdefeudis, F.Clostre. Effects of Ginkgo Biloba on Arterial Smooth Muscle Responses to Vasoactive Stimuli. // gen Pharmacol. –1982. –V.13. –P.169–171. 20. Barker ww, luis ca, kashuba A. et al. Relative Frequencies of Alzheimer Disease, Lewy Body, Vascular and Frontemporal Dementia, and HippoCapal Sclerosis in the State of Florida Branin Bank. // Alzheimer disord. –2002. –V.16. –P.203–212. 21. Bars P., Katz M., Berman N., ITIL T., Freedman A., SChatzberg A. A Placebo - Controlled, Double - Blind, Randomized Trial of an Exteact of Ginkgo Biloba FOR DEMENTIA. // Jama. - 1997. –VOL.278, N.16. –P.1327–1332. 22. Cummings JL Vascular Subcortical Dementias: Clinical Aspects. // in: vascular dementia. Ethiological, Pathogenetic, Clinical and Treatment Aspects. Ed. By Lacarlson, Cggottfries, B.Winblad. –Basel etc.: S.Karger. –1994. –P.49–52. 23. Deby C., G.deby - Dupont, M.Dister, J.PinCmail. Efficency of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGB 761) In Neutralizing Ferrylion --induced Peroxidations: Therapeutic Implications. // in: c.Ferradini, mtdroy --lefaix, Y.Christen (EDS): Ginkgo Biloba Extract as Free Radical Scavenger. Advances in Ginkgo Biloba Extract Research; –1993. –V.2. - P.13–26. 24. Dubois B., A.Slachevsky, I.litvan, B.Pillon. The FAB: A Frontal Assessement Battle at Bedside. //Neurology. –2000. –V.55. –P.1621–1626. 25. Erkinjuntti T., Roman G., Gauthier S. et al. Emerging therapies for Vascular Dementia and Vascular Cognitive Impairment. // Stroke. –2004. —Vol.35. P.1010–1017. 26. Erkinjuntti T., Roman G., Gauthier S. Treatment of Vascular Dementia - Evidence from Clinical Trials with Cholineestrase Inhibitors. // J Neurol Sci. –2004. —Vol.226. –P.63–66. 27. Erkinjuntti T., Kurz A., Gauthier S. et al. Efficacy of Galantamine in Probable Vascular Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease Combined with Cerebrovascular Disease: A RANDOMISED TRIAL. // Lancet. –2002. —Vol.359. — No. 9314. –P.1283–1290. 28. Folstein MF, Sefolstein, PRMCHUGH. Mini - Mental stat: A Practical Guidefor Grading The Mental State of Patients for the Clinician. // j psych res. –1975. –V.12. –P.189–198. 29. Franco L., G.cuny, FMCNANCY. Multicentre Study of the Efficacy of Tanakan (EGB 761) in the Treatment of Age - SSOCIETED MEMORY IMPARONT. // Rev de Geriatrie. –1991. –V.4. –P.233–236. 30. Fu C., Chute DJ, Farag Es, Garakian J. et al. Comorbidity in Dementia: Anutopsy Study. // Arch Pathol Lab Med. –2004. —Vol.128. — No. 1. –P.32–38. 31. Gardes-albert M., A.Khalil, A.Fortun et al. Protective Effect of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGB 761) Against The Lipid Peroxidation of Low Density Lipoproteins Initiated by .02 Free Radicals. // in: Y.Christen, Y.courtois, Mtdroy --lefaix (EdS) Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGB 761) On AGING AND AGE - Related Disorders. Advances in Ginkgo Biloba Extract Research. –V.4. Elsevier, Paris. –1995. –P.49–64. 32. Gardes-albert M., C.Ferradini, A.Sekaki, Mtdroy - Lefaix. Advances in Ginkgo Biloba Extract Research. –1993. –V.2. - P.1–12. 33. Grylewski RJ, R.Korbut, J.Robak, J.Swies. On the Mechanism of Antithrombotic Action of Flavinoids. // Biochem Pharmacol. –1987. –V.36. –P.317–322. 34. Hachinski V. 35. Hachinski VC, Lassen Ma, Marshall J. Multi - Infarct Dementia. A Case of Mental Deterioration in the Elderly. // Lancet. –1974. –V.2. –P.207–210. 36. Hershey La, Olszewski Wa Ischemic Vascular Dementia. // in: Handbook of Demented Illnesses. Ed. by jcmorris. –New york etc.: Marcel Dekker, Inc. –1994. –P.335–351 37. Hofferberth B. The Efficacy of EGB 761 in PATIENTS WITH SENILE DEMENTIA of the Alzheimer Type, A Double Blind - Controlled state Nvestigation. // hum psychopharmacol. –1994. –V.9. –P.215–222. 38. Holdago Madruga M., S. de Castro, JFMACIAS - NUNEZ. Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGB 761) Ob Brain Anging and Oxygen Free Radicals Metabolism in Rat. // in: Y.Christen, Y.courtois, Mtdroy --lefaix (EDS): Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGB 76) On AGENS and AGE - Related Disorders. Advances in Ginkgo Biloba Extract Research. –V.4. Elsevier, Paris. –1995. –P.71–76. 39. Hulette CM Brain Banking in the United States. // J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. –2003. —Vol.62. –N.7. –P.715–722. 40. Israel L., M.Myslinski, E.Dell'accio et al. Oneset of Memory Disorders: Specific and Combined Contribution of Memory - Training Programs and Ginkgo Biloba (EGB 761) Treatment. // in: Y.Christen, Y.courtois, Mtdroy --lefaix (EDS): Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGB 761) On AGING AND AGE - RELEETED DISORDERS. Advances in Ginkgo Biloba Extract Research. –V.4. Elsevier, Paris. –1995. –P.119–130. 41. IQBAL K., B.Winblad, T.NISHUMURA,, N.TakeDa, H.Wishewski (EDS). Alzheimer's disease: Biology, Diagnosis and Therapeutics. //J.willey and sons ltd. –199714. 42. Kanowski S. Proof of Efficacy of the Ginkgo Biloba Special Extract (EGB 761) In Outpatients Suffering Fromary Degeneration of the alzheimer's Type And Mul I - Infarct Dementia. // in: Y.Christen, Y.courtois, Mtdroy --lefaix (EDS): Effec S of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGB 761) ON AGING AND AGE - RELEETED DISORDERS. Advances in Ginkgo Biloba Extract Research. - V.4. Elsevier, Paris. –1995. –P.149–158. 43. Knopman ds, Parisi Je, Boeve Bf et al. Vascular Dementia in A Population - Based Autopsy Study. // Arch Neurol. –2003. —Vol.60. –P.569–575. 44. Kumar V., Messina J., Hartman R., Cicin - Saina A. Pressence of Vascular Risk Factors in Ada Patients Greater Response to Cholinesterase Inhibition. // Neurobiol. Aging. –2000. —Vol.21. –N.1S. –P.S218. 45. Packer L., N.haramaki, T.Kawabata et al. Gingko Biloba Extract (EGB 761): Antioxidant Action and Prevention Stress --induced Injury. // in: Y.Christen, Y.courtois, Mtdroy --lefaix (EDS): Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGB 761) ON AGE and AGE - Related Disorders. Advances in Ginkgo Biloba Extract Research. –V.4. Elsevier, Paris. –1995. –P.23–48. 46. Petersen RS, Smith GE, Wang SC et al Mild Cognitive Impairment: Clinical Characterization and Outcome // Arch. Neurol. - 1999. - Vol. 56. - P. 303–308. 47. Rosvold he The Frontal Lobe System: Cortical - Subcortical InternationalShips. // Acta Neurobiol Exp. –1972. - V.32. –P.49–460. 48. Saint - Cyr Ja, Aetaylor, K.Nikolson. Behavior and Vasal Ganglia. // in: “Behavial neurology of movement disorder”. Wjweiner, Alang (EDS). —Adv Neurol. –1995. –V.65. –P.1–29.

Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Share the article on social networks

Recommend the article to your colleagues