general description

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) due to rupture of a cerebral aneurysm (I60) is a sudden onset of hemorrhage in the subarachnoid space of the brain and/or spinal cord.

Incidence: 14–20 per 100 thousand people. SAH is most often observed between 40 and 60 years of age.

Risk factors: arterial hypertension, head trauma or injury, atherosclerosis, smoking, alcohol abuse, physical or emotional stress. In 75–80% of cases, the cause of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage is the rupture of an arterial aneurysm.

HEMORRHAGE

HEMORRHAGE

(syn.:

hemorrhage, extravasation

) - accumulation of blood spilled from the vessels in the tissues and cavities of the body.

The spilled blood can push apart and separate tissue elements, saturating and destroying the parenchyma. Similar K. are called hemorrhagic infiltration. Extensive K., surrounded by dense tissue forming a capsule, is called hematoma (see). The formation of a hematoma is often accompanied by detachment or destruction of tissue. Flat hemorrhages in the thickness of the skin and mucous membranes are called bruises, small spotty and pinpoint hemorrhages in the skin, mucous and serous membranes are called petechiae or ecchymoses. Multiple petechial type hemorrhages in the substance of the brain, observed with fat embolism of cerebral vessels, with a sudden disruption of the outflow of blood in the superior vena cava system, with acute inf. diseases are called hemorrhagic purpura. Massive simultaneous K. in some organs, accompanied by a sharp disruption of their function, is called apoplexy. Most often, apoplexy of the brain is observed during a stroke (tsvetn. Fig. 1 and 2), adrenal glands, apoplexy of the ovary (see). Rice.

1 and 2. Microscopic specimens of brain tissue with perivascular hemorrhages (hypertension): Fig. 1 — ring-shaped hemorrhages (indicated by arrows); rice. 2— hemorrhages under the ependyma of the ventricles (indicated by arrows). K. is based on the same factors as with bleeding (see). The cause of K., as a rule, is a violation of the integrity of the wall of the heart or blood vessels, or increased permeability. Hemorrhages from rupture (haemorrhagia per rhexin) are observed with injuries, as well as damage to the cardiovascular system by any pathol, process. These are ruptures of the walls of the heart in the area of infarction (see), supravalvular rupture of the aorta (see) due to necrosis of its middle shell due to hypertension, ruptures of aneurysms (see), including aneurysms of cerebral vessels (see) , ruptures of the tense capsule of organs (liver, spleen).

Rice. 3. Microscopic specimen of the gastric mucosa with hemorrhage in the area of hemorrhagic erosion (indicated by arrows).

Another cause of K. is the erosion of the vessel wall (haemorrhagia per diabrosin) by the cells of a malignant tumor, its melting under the action of proteolytic enzymes of pus, the tuberculous process, under the influence of digestion by gastric juice, for example, the walls of blood vessels at the bottom of the ulcer or erosion of the stomach (color. Fig. 3 ) and etc.

Rice. 4. Microscopic specimen of the adrenal gland with hemorrhages in the cortex during bacterial shock (indicated by arrows).

K. can occur through diapedesis (haemorrhagia per diapedesin). These K., as a rule, have the form of petechiae and ecchymoses, located in the form of a rim around the capillary or arteriole - ring-shaped K. Diapedetic K. (see Diapedesis) arise in the tissue of parenchymal organs, but are observed mainly in the skin and under the serous membranes , as well as in the thickness of the mucous membranes. Similar K. are found in many inf. diseases (typhoid fever, malaria, etc.), vitamin deficiencies, leukemia, acute fibrinolysis, as well as intensive anticoagulant therapy (tsvetn. Fig. 4). In such cases, K. often take on a widespread character, and then they talk about hemorrhagic diathesis.

Petechial diapedetic K. (ecchymoses) are of great diagnostic value. Thus, subendocardial ecchymoses of the left ventricle of the heart (Minakov spots) are characteristic of acute hypoxia of any etiology, K. in the gastric mucosa - in case of death from cooling, petechiae of the conjunctiva of the eyeball - in typhus (see Chiari-Avtsyn symptom) and sepsis, multiple petechiae in the skin of the chest - with compression of the chest, etc.

K. arise not only during life, but also posthumously. Postmortem K. can arise as a result of injury within 1 - 2 days. after cardiac arrest. They are especially often formed during closed cardiac massage, used for the purpose of resuscitation. Differential diagnosis of intravital and postmortem K. presents significant difficulties.

The blood released into the tissue coagulates and undergoes further transformations. Hemoglobin, released from disintegrated red blood cells, is partially resorbed by macrophages, turning into hemosiderin, determined in histol, sections using a reaction to iron; the other part of hemoglobin, without the participation of cellular elements, is converted into Hematoidin, which is usually located in the central areas of the hematoma. Hematoidin can subsequently be transformed into the bile pigment - bilirubin. The transformation of hemoglobin is associated with a change in the color of the skin bruise from purplish-red to blue (hemosiderin) and yellow (bilirubin). Fibrin bundles undergo resorption or organization and are eventually replaced by connective tissue.

Wedge, manifestations of K. are determined by their localization, speed of development and size.

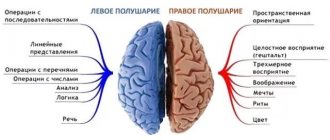

K. in the brain are characterized by certain neurol, symptoms due to localization. K. in the brainstem and extensive K. in the area of the subcortical nodes with a breakthrough into the ventricles of the brain are of particular danger to life. Rupture of a cerebral artery aneurysm leads to extensive subarachnoid hemorrhages. Hemorrhages into the soft meninges with an arterial aneurysm are often repeated. In case of traumatic brain injury, a subdural hematoma may occur, accompanied by a characteristic wedge phase, flow; immediately after the injury there may be a period of imaginary well-being, followed by a comatose state as the volume of the subdural blood increases.

K. into vital organs may not cause significant blood loss and circulatory hypoxia. Only a massive retroperitoneal hematoma, resulting from damage to large arteries of the abdominal cavity or rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, is accompanied by blood loss of up to 3-4 liters.

K. in the tissue is often combined with K. in the body cavity: pleural (see Hemothorax), abdominal (see Hemoperitoneum), pericardium (see Hemopericardium), gland.-kish. tract. Wedge, the picture in these cases is determined mainly by the degree of blood loss (see), and K. into the pericardial cavity, usually associated with a violation of the integrity of the heart cavity or intrapericardial aorta, is fatal.

Diapedetic K. in the skin and mucous membranes, being a manifestation of severe general diseases, as a rule, do not themselves cause serious complications. However, their localization in vital organs, for example, in the brain, can cause severe disorders. The mucous membrane of the stomach in the area of petechial K., as a rule, undergoes autolysis under the influence of hydrochloric acid and peptic enzymes of gastric juice with the formation of erosions and acute ulcers, which in turn are complicated by gastric bleeding.

With extensive K., jaundice of the skin and mucous membranes occurs due to the conversion of hemoglobin into bilirubin. Resorption of hemoglobin from extensive hematomas is accompanied by hemoglobinemia (see) and hemoglobinuria (see), and with simultaneous damage to large muscle masses - myolysis and myoglobinuria (see). Possible outcomes of K. include suppuration, calcification, and necrosis.

Rice. 1. X-ray of the neck (the arrow indicates a calcified area of hemorrhage). Rice. 2. X-ray of the elbow joint (arrows indicate a calcified area of hemorrhage).

When calcification occurs, it is detected by radiography, usually 1 to 2 months later. after injury, and sometimes a little earlier in the form of a conglomerate of uneven spotty or solid shadows (Fig. 1 and 2). At first, calcification appears as a cloud-like, low-intensity shadow; later such shadows become denser and increase in volume. Calcification is usually located in the muscle, isolated from the bone.

K.'s calcification often passes into ossification as metaplasia or through the cartilaginous stage. Roentgenol, the picture of K.’s ossification sometimes acquires similarities to osteogenic sarcoma.

In the differential diagnosis, a history of trauma, the originality of rentgenol, pictures of calcified K. are taken into account - lack of connection with the bone, typical localization of osteogenic sarcoma in parts of the bone with a thin layer of muscles (for example, in the epicondyles of the femur), while bone formation that occurs in the area of the hematoma , are usually found in the area of thick layers of muscle. Difficulties in diagnosis are possible in cases of ossification intimately fused with the periosteum.

Most small K. do not require special treatment. In case of massive aneurysms caused, for example, by damage or spontaneous rupture of an aneurysm of large arteries, etc., emergency surgical intervention is indicated.

Bibliography:

Dyachenko V. A. X-ray diagnostics of calcifications and heterogeneous ossifications, M., 1960, bibliogr.; Isakov Yu. V. Acute traumatic intracranial hematomas, M., 1977, bibliogr.; Koltover A. N. id. Pathological anatomy of cerebral circulation disorders, M., 1975, bibliogr.; Lebedev V.V., Ioffe Yu.S. and Ostrovskaya I.M. Surgery of acute cerebral strokes, M., 1970, bibliogr.; StrukovA. I. Pathological anatomy, M., 1971.

N. K. Permyakov; V. A. Dyachenko (rent.).

Clinical picture

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is manifested by sudden, severe pain in the head (a feeling of a “blow to the head”), and a short-term loss of consciousness is possible. At the same time, nausea, vomiting, and photophobia appear. During the first days, a fever of up to 37–38 °C may be observed. A neurological examination of the patient reveals cerebral syndrome (90%), meningeal syndrome, arterial hypertension (50%), bradycardia (30%), impaired consciousness up to coma (up to 50%), there may be epileptic seizures, hemorrhage in the eyeball (symptom Terson). At 2–3 weeks, focal symptoms of brain damage may occur (25%).

Diagnostics

Lumbar puncture (bloody cerebrospinal fluid flowing out under increased pressure).- Computer and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (presence of blood in the subarachnoid space).

- Cerebral angiography (visualization of an aneurysm).

Differential diagnosis:

- Parenchymal hemorrhage.

- Brain contusion.

- Subdural hematoma of the brain.

- Hemorrhage into a brain tumor.

Classification

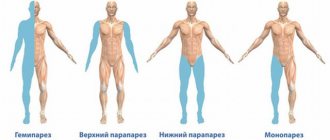

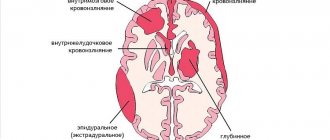

HI (non-traumatic/spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage), depending on the location of the bleeding, is divided into the following types:

- intracerebral/parenchymal hemorrhage;

- intrathecal hemorrhage (subarachnoid, epidural, subdural);

- ventricular/intraventricular hemorrhage;

- mixed hemorrhage (parenchymal - subarachnoid, parenchymal - ventricular, subarachnoid - parenchymal - ventricular, etc.).

With intracerebral/parenchymal hemorrhage, the localization of the spilled blood is observed directly in the thickness of the brain substance. Intrathecal hemorrhage is characterized by the accumulation of blood in the epidural (between the cranium and the dura mater), subdural (between the dura mater and the arachnoid mater) and subarachnoid (between the arachnoid and pia mater) spaces. It should be noted that epidural and subdural hemorrhage most often occur with trauma, although non-traumatic subdarial and epidural hemorrhages (stroke hematomas) also occur. hemorrhage is characterized by blood entering the ventricles of the brain either when there is bleeding in this area or when a growing intracerebral hemorrhage breaks through. hemorrhage is characterized by the accumulation of blood within several anatomical structures.

The type of hemorrhage largely depends on the etiological factor. Primary and secondary intracerebral hemorrhages are distinguished.

Based on the depth of location and relation to the internal capsule, the IUD is usually divided into:

- lateral/putamenal ICHs, which are located lateral to the internal capsule, in the subcortical nuclei and, depending on the volume, extend to the putamen, globus pallidus or septum;

- medial/thalamic ICHs, located medially from the internal capsule, in the area of the visual thalamus and subthalamus, can spread to the midbrain and penetrate the ventricular system, often formed as a result of diapedetic impregnation;

- mixed IUDs located within several anatomical structures.

Based on the location of the lesion, ICH is classified into:

- deep-seated hemorrhages affecting the deep parts of the brain, internal capsule, subcortical nuclei;

- subcortical/lobar hemorrhages located in the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres, close to the cortex, limited to one lobe of the brain; often occur in elderly patients (over 70 years of age) and may be caused by CAA;

- extensive hemorrhages involving two or more lobes of the brain.

By size, an intracerebral hematoma can be classified as:

- small (up to 20 ml, CT diameter no more than 3 cm);

- medium (from 20 ml to 50 ml, CT diameter 3–4.5 cm);

- large (more than 50 ml, CT diameter more than 4.5 cm).

Table 1. Classification of intracranial hemorrhages

| Classification of intracranial hemorrhages | Pathophysiological changes |

| Primary parenchymal hypertensive hemorrhage | Associated with arterial hypertension. Rupture of small arterioles due to degenerative changes due to uncontrolled arterial hypertension. |

| Cerebral amyloid angiopathy | Rupture of small and medium-sized arteries in the area of β-amyloid deposits. The development of lobar hemorrhages is typical in patients over 70 years of age. |

| Secondary parenchymal hemorrhages | |

| Hemorrhagic infarction | Hemorrhagic transformation of cerebral infarction. |

| Hemorrhages while taking anticoagulants. Coagulopathies | The pathophysiology is similar to primary parenchymal hemorrhage. Often affects patients with vasculopathies associated with chronic arterial hypertension or amyloid angiopathy, which may increase the risk of conditions with overt or subclinical manifestations. |

| Substance abuse (cocaine, amphetamine, ecstasy, PCP - phenylcyclidine, angel dust, drugs that reduce swelling of the mucous membrane of the upper respiratory tract and drugs that reduce appetite). | It may develop against the background of a vascular anomaly. |

| Infective endocarditis | Formation of mycotic aneurysms in the distal parts of the cerebral arteries due to septic lesions. |

| Vasculitis | Rupture of the walls of small and medium-sized arteries affected by an inflammatory or degenerative process. |

| My-my syndrome | Stenotic lesions of large vessels. |

| Thrombosis of cerebral venous sinuses | Consequences of hemorrhagic transformation of venous infarction. |

| A brain tumor | Consequences of necrosis and hemorrhage into tumor tissue with a rich blood supply. |

| Traumatic brain injury | Hemorrhage due to traumatic brain injury. |

| Cerebral aneurysm | Rupture of the saccular expansion of a medium-diameter vessel. Usually associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). |

| Arteriovenous malformation | Rupture of abnormal small vessels connecting arteries and veins. |

| Venous angioma | Rupture of abnormal dilated venules. |

| Cavernous angioma | Rupture of capillary-like vessels surrounded by connective tissue. |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage: aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, non-aneurysmal perimesencephalic hemorrhage, dural malformation, trauma, vascular dissection. | The pathophysiological mechanisms are similar to those described above, but the blood spreads in the subarachnoid space. Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal hemorrhage is a benign variant with an unknown cause, possibly related to venous pathology, with the center of hemorrhage located primarily in the peripontine cistern. |

| Subdural hemorrhage | Rupture of pontine veins |

| Epidural hemorrhage | Arterial epidural hemorrhage develops due to ulceration of the branches of the meningeal arteries, while venous hemorrhage is a consequence of bleeding from the sinuses of the brain. |

Table 2. Scale for assessing the likelihood of a secondary (vascular) nature of intracerebral hemorrhage based on clinical signs (SICH scale) (JE Delgado Almandoz, PW Schaefer, 2010)

| Index | Points |

| Estimation of probability using non-contrast CTa | |

| High | 2 |

| Moderate | 1 |

| Low | |

| Age group | |

| 18–45 years old | 2 |

| 46–70 years | 1 |

| ≥71 years | |

| Floor | |

| Female | 1 |

| Male | |

| The patient has never previously had hypertension or bleeding disordersb | |

| Yes | 1 |

| No | |

Note: The total SICH score is calculated by summing the scores for each patient.

a High probability: non-contrast CT shows one of the following: 1) enlarged vessels or calcifications within the edges of the ICH or 2) reduced x-ray density in the area of the dural sinus or cortical veins with intact venous drainage in the area of the ICH.

Low probability: according to the study, the ICH is located in the subcortical ganglia, thalamus, or brain stem.

Moderate Likelihood: The study results do not meet the criteria for ICH with a high and low probability of secondary causes.

b Bleeding disorders - laboratory test data at the time of admission INR>3, APTT>80 seconds, platelet count <50 * 109 or daily use of antiplatelet agents.

In patients with a SICH score > 2 points, the likelihood of a secondary (vascular) nature of intracerebral hemorrhage increases.

Risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage

There are modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for ICH.

Modifiable risk factors:

- arterial hypertension;

- current smoking;

- alcohol abuse;

- reduced levels of low-lipoproteins, low levels of triglycerides;

- taking anticoagulants;

- taking antiplatelet agents;

- drugs with sympathomimetic effects (cocaine, heroin, amphetamine, phenylpropanolamine and ephedrine).

Non-modifiable risk factors:

- elderly age;

- male gender;

- belonging to the Mongoloid race;

- cerebral amyloid angiopathy;

- cerebral microbleeds;

- chronic kidney diseases.

Treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage resulting from rupture of a cerebral aneurysm

Treatment: strict bed rest, support of vital functions, sedatives, narcotic analgesics, repeated lumbar punctures, coagulants in the first two days, calcium channel antagonists, decongestants, anticonvulsants. Surgical treatment is also used. Treatment is prescribed only after confirmation of the diagnosis by a medical specialist.

Essential drugs

There are contraindications. Specialist consultation is required.

- Mannitol (diuretic, decongestant). Dosage regimen: intravenous, slow stream or drip. Therapeutic dose is 1-1.5 g/kg body weight, prophylactic dose is 0.5 g/kg. The daily dose should not exceed 140-180 g.

- Furosemide (diuretic). Dosage regimen: intramuscularly or intravenously (slow stream) 20-60 mg 1-2 times a day, if necessary, the dose can be increased to 120 mg. The drug is administered for 7-10 days or more, and then the drug is taken orally.

- Ketoprofen (analgesic). Dosage regimen: orally, during meals; tablets 100 mg 3 times a day or 150 mg/day. (retard) with an interval of 12 hours. Capsules - 50 mg in the morning and afternoon, 100 mg in the evening.

- Nifedipine (calcium channel blocker, antihypertensive drug). Dosage regimen: intravenous drip, infusion rate should be 0.6-1.2 mg/h; the maximum daily dose is 30 mg, treatment period is 2-3 days. To continue therapy, it is advisable to switch to long-acting oral forms.

- Enalapril (antihypertensive drug, ACE inhibitor). Dosage regimen: the initial oral dose is 10-20 mg, depending on the severity of arterial hypertension and is prescribed 1 time per day.

- Carbamazepine (anticonvulsant). Dosage regimen: treatment begins with a dose of 0.1 g orally 2 times a day. Then the daily dose is gradually increased by 1/2-1 tablet. to minimally effective (0.4 g per day). It is not recommended to exceed a dose of more than 1200 mg/day.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Pre-hemorrhagic period

Precursors of SAH are observed in 10-15% of patients. They are caused by the presence of an aneurysm with thinned walls through which the liquid part of the blood leaks. The time of occurrence of precursors varies from a day to 2 weeks before SAH. Some authors distinguish it as the pre-hemorrhagic period. At this time, patients note transient cephalgia, dizziness, nausea, transient focal symptoms (damage to the trigeminal nerve, oculomotor disorders, paresis, visual impairment, aphasia, etc.). In the presence of a giant aneurysm, the clinic of the pre-hemorrhagic period has a tumor-like character in the form of progressive cerebral and focal symptoms.

Acute period

Subarachnoid hemorrhage manifests itself with acute, intense headache and disturbances of consciousness. With aneurysmal SAH, unusually strong, rapidly growing cephalalgia is observed. With arterial dissection, the headache is biphasic. Short-term loss of consciousness and confusion lasting up to 5-10 days are typical. Possible psychomotor agitation. Prolonged loss of consciousness and the development of severe disturbances (coma) indicate severe bleeding with bleeding into the cerebral ventricles.

The pathognomonic sign of SAH is the meningeal symptom complex: vomiting, neck stiffness, hyperesthesia, photophobia, meningeal symptoms of Kernig and Brudzinski. It appears and progresses on the first day of hemorrhage, can have varying severity and persist from several days to a month. The addition of focal neurological symptoms on the first day speaks in favor of combined parenchymal-subarachnoid hemorrhage. The later appearance of focal symptoms may be a consequence of secondary ischemic damage to brain tissue, which is observed in 25% of SAH.

Typically, subarachnoid hemorrhage occurs with a rise in temperature to febrility and viscero-vegetative disorders: bradycardia, arterial hypertension, and in severe cases, respiratory and cardiac dysfunction. Hyperthermia can be delayed and occurs as a consequence of the chemical action of blood breakdown products on the cerebral membranes and the thermoregulatory center. In 10% of cases epileptic seizures occur.

Atypical forms of SAH

In a third of patients, subarachnoid hemorrhage has an atypical course, masquerading as a paroxysm of migraine, acute psychosis, meningitis, hypertensive crisis, and cervical radiculitis.

- Migraine form

. Occurs with the sudden onset of cephalgia without loss of consciousness. The meningeal symptom complex appears 3-7 days later as the patient’s condition worsens. - False hypertensive form.

Often regarded as a hypertensive crisis. Because cephalalgia manifests itself against the background of high blood pressure numbers. Subarachnoid hemorrhage is diagnosed during further examination of the patient if the condition worsens or rebleeds. - The false inflammatory form

imitates meningitis. Cephalgia, febrility, and severe meningeal symptoms are noted. - The false psychotic form

is characterized by a predominance of psychosymptomatics: disorientation, delirium, severe psychomotor agitation. It is observed when an aneurysm of the anterior cerebral artery, which supplies blood to the frontal lobes, ruptures.

Recommendations

Consultation with a neurosurgeon, computed tomography of the brain, and cerebral angiography are recommended.

| • | Leading specialists and institutions for the treatment of this disease in Russia: |

| Doctor of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Russian State Medical University, Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences Gusev E.I.; Director of the Research Institute of Neurosurgery named after. Burdenko N.N. Konovalov A.N. | |

| • | Leading specialists and institutions for the treatment of this disease in the world: |

| G. AVANZINI, Italy; Professor Duke Samson, USA. |

Intracranial hemorrhage

Intracranial hemorrhage is a collective concept that describes many different pathologies characterized by extravasal accumulation of blood in various intracranial spaces and brain parenchyma. The simplest division of intracranial hemorrhages is based on localization:

- intra-axial hemorrhage intracerebral hemorrhage hemorrhage into the basal ganglia (medial hematoma)

- lobar hematoma (lateral gametoma)

- hemorrhage in the pons

- intracerebellar hemorrhage

- epidural hematoma

Intracranial hemorrhages can be divided according to their causes, although in most cases one etiology can lead to different manifestations of hemorrhages:

- trauma epidural hematoma

- subdural hematoma

- subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)

- hemorrhagic brain contusion

- saccular aneurysm

Diagnostics

In general, imaging findings depend on the timing of hemorrhage and are discussed in a separate article, Evolution of Intracranial Hemorrhage

CT scan

CT examination is almost always the first modality used in the evaluation of patients with suspected intracranial hemorrhage. Fortunately, acute hemorrhage has a pronounced hyperdense density relative to the brain parenchyma, and thus does not present difficulties in diagnosis.

CT angiography (CTA) is increasingly being used to evaluate for vascular causes, especially in subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage, if patient demographics or the location/appearance of the hemorrhage indicate that a primary cause of the hemorrhage is unlikely.

Similarly, CT venography is used to reliably assess the patency of the dural venous sinuses.

Magnetic resonance imaging

An MRI is usually performed to look for the cause of abnormal findings, especially if a tumor is suspected. Evaluation of MR images can be somewhat challenging depending on the sequence used, the time elapsed since hemorrhage, and the size and location of the hemorrhage.

Angiography

Cerebral angiography is performed when a vascular anomaly is suspected, but CTA data are insufficient.

Incidence (per 100,000 people)

| Men | Women | |||||||||||||

| Age, years | 0-1 | 1-3 | 3-14 | 14-25 | 25-40 | 40-60 | 60 + | 0-1 | 1-3 | 3-14 | 14-25 | 25-40 | 40-60 | 60 + |

| Number of sick people | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 14 | 20 | 16 |

Symptoms

| Occurrence (how often a symptom occurs in a given disease) | |

| Sudden intense headache | 90% |

| Vomiting of various types, including indomitable | 90% |

| Nausea | 90% |

| Fainting (loss of consciousness) | 80% |

| Intolerance to bright light (photophobia, light sensitivity) | 70% |

| General increase in body temperature (fever, fever) | 50% |

| Numbness of one half of the body | 30% |

| Attacks of seizures with or without loss of consciousness (convulsions, convulsive seizures, convulsions, convulsions) | 10% |

| Transient speech impairment (absence or difficulty speaking during the day) | 5% |