Clinical syndromes of cerebral hemorrhage in hypertension

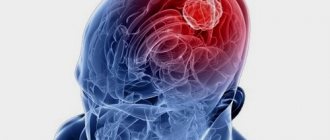

Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhages can occur in any patient with hypertension. But more often hemorrhages occur with constant essential arterial hypertension. Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhages almost always occur while the patient is awake, but are not always necessarily provoked by overexertion. Unlike sudden embolisms of cerebral vessels, hemorrhagic stroke develops within a few minutes, and its symptoms are determined by the location and size of the hemorrhage.

Hemorrhage into the putamen of the brain

Most often, in patients with arterial hypertension (hypertension), one has to observe the clinical picture of hemorrhage in an area of the brain such as the putamen. When hemorrhaging at this location, the hematoma also affects the nearby internal capsule of the brain.

MRI of the brain of a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage due to hypertension. An acute hematoma is visible in the right external capsule and insular cortex (indicated by an arrow).

An axial CT scan of the brain shows a hematoma located in the left external capsule and putamen (indicated by an arrow).

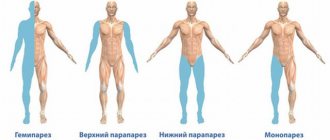

With extensive hemorrhages, the patient immediately loses consciousness, falls into a coma, and develops paralysis of the muscles of half the body (hemiplegia). However, more often he manages to complain about unpleasant sensations in his head. Within a few minutes, a distortion of the face, confusion of speech or its complete absence (aphasia) appear. The patient gradually develops weakness in the limbs, and there is a tendency to turn the eyes in the direction opposite to the side of paralysis. Typically these phenomena develop within 5–30 minutes. Such dynamics of symptoms most likely indicate intracerebral hemorrhage.

Weakness in the limbs increases to complete muscle paralysis (plegia). The patient does not respond to painful stimuli, a pathological Babinski symptom appears, speech disappears (aphasia) when the dominant hemisphere is affected by a hematoma. The patient's consciousness changes from drowsy to stupor. In particularly severe cases, symptoms of compression of the upper part of the brain stem quickly arise. The patient's ensuing coma is accompanied by deep, irregular or intermittent breathing, with dilation of the pupil (on the side of the hemorrhage) and its lack of reaction to light, bilateral Babinski's sign and decerebrate muscle rigidity. The increase in neurological symptoms in the period from 12 to 72 hours after its onset is caused by the development of edema of the brain tissue around the hematoma (perifocal edema), and not by repeated rupture of the vessel.

Causes

According to ICD10, intracerebral hemorrhage occurs as a result of the presence of both predisposing factors and factors initiating vessel rupture. Predisposing factors include:

- Vessel aneurysm, characterized by local dilatation of the wall of a vessel (usually an artery). Aneurysms can be congenital or acquired.

- Vascular malformation characterized by the irregular connection of many small arteries and veins without a capillary bed.

- Vasculitis associated with inflammation of the vessel wall.

- Atherosclerotic damage to the vessel wall.

Read about risk factors for cerebral hemorrhage in newborns: the main causes of the pathology.

Find out the dangers of extensive cerebral hemorrhage: consequences for patients.

However, predisposing factors alone are not enough. For a vessel to rupture, the initiating factor must act:

- hypertensive crisis (often in the elderly);

- bleeding disorders;

- a number of narcotic substances that disrupt vascular tone;

- intratumoral hemorrhage.

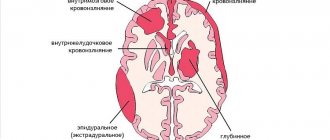

The combined action of several factors leads to rupture of the blood vessel, which leads to the development of symptoms. Types of hemorrhage:

- Subdural - characterized by the accumulation of blood under the dura mater.

- Subcortical cerebral hemorrhage in the hemispheres with accumulation of blood at the border between the cortical sections.

- Subarachnoid - accumulation of blood under the arachnoid mater.

- Intraventricular, characterized by blood entering the ventricles of the brain.

- Mixed, combining several types of hemorrhages.

CT and MRI diagnostics help determine the specific type of hemorrhage.

Hemorrhage into the thalamus of the brain

Thalamic hemorrhage of moderate size also causes the patient to experience paralysis or partial weakness of the muscles of half the body (hemiplegia, hemiparesis) due to compression or stratification by the hematoma of adjacent structures of the internal capsule. The patient will have impaired pain, temperature, proprioceptive and tactile sensitivity of half the body. With lesions of the dominant hemisphere, speech disorder (dysphasia) may occur, often with preserved repetition aloud.

MRI of the brain of a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage in the thalamus (indicated by arrows).

If a hemorrhage occurs in a patient with arterial hypertension in the non-dominant hemisphere of the brain, then there will be a violation of goal-directed actions and recognition (apractoagnosia). Developing homonymous visual field defects in the patient usually then disappear within a few days. Thalamic hemorrhage, spreading inward and downward into the subthalamus, causes oculomotor disorders. They appear including:

- in the form of vertical gaze paralysis

- forced downward rotation of the eyeballs

- different pupil diameters (anisocoria) with the absence of their reaction to light

- strabismus with deviation of the eyeball opposite to the side of the hemorrhage, downward and inward

- on the side of the hemorrhage there is a drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis) and constriction of the pupil (miosis)

- lack of convergence

- disturbances in horizontal gaze movements (paresis or pseudoparesis of the VI nerve)

- retraction nystagmus

- swelling of the eyelids

Shortening of the neck may be noted. Thalamic hemorrhage in the non-dominant hemisphere of the brain sometimes causes the patient to be unable to speak (mutism).

Treatment of patients with intraventricular hemorrhage and cerebral edema

The main condition determining the success of therapy is its earliest possible start.

At the stage of resuscitation, treatment is aimed at maintaining cardiac activity, restoring breathing and stabilizing basic blood parameters. If necessary, medications are administered for:

- stopping seizures (Diazepam, Phenorelaxan);

- blood pressure reduction (Magnesium sulfate);

- reducing swelling (Mannitol, glucose 40%, Lysine escinate, Lasix);

- stopping vomiting (Cerucal).

In the first six hours, the issue of carrying out the operation is decided. It can take place in the form of drainage of the cerebral ventricle or removal of contents during puncture. This treatment helps reduce tissue compression and intracranial hypertension. If emergency measures are successfully carried out, patients are prescribed therapy aimed at restoring brain tissue.

To improve metabolic processes, Actovegin, Lucetam, and Glycine are prescribed. Also shown:

- antioxidants (Mexidol, Mildronate, vitamin E);

- calcium blockers (Nimotop, Nicardipine);

- metabolism stimulants (Cytochrome C, Riboxin, ATP).

Hemorrhage into the pons (brain stem)

After hemorrhage into the pons, the patient usually falls into a deep coma within a few minutes. The clinical picture includes paralysis of the muscles of all extremities (tetraplegia), severe decerebrate rigidity, pupillary constriction (miosis) with up to 1 mm and lack of response to light. In a patient with hemorrhage into the pons, reflex horizontal eye movements caused by turning the head (doll's eye symptom) and irritation of the ears with cold water (caloric test) will be impaired. These patients often experience hyperventilation, high blood pressure, and excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis). As a rule, the death of a patient with hemorrhage into the bridge occurs within a few hours. In rare cases, consciousness remains intact and clinical manifestations indicate a small lesion in the pons. These are symptoms such as disorders of the movements of the eyeballs in the horizontal plane, gross speech disorder (dysarthria), cross motor and sensory disorders, constriction of the pupils (miosis), cranial nerve palsies, bilateral symptoms of involvement of the pyramidal tracts.

Hemorrhage into the cerebellum

Hemorrhage into the cerebellum usually develops within several hours. With this localization of hemorrhage, loss of consciousness in the patient is rarely observed at first. Repeated vomiting is typical, the patient is unable to walk or stand. These clinical signs appear early and should raise suspicion of this diagnosis, which allows the neurosurgeon to promptly decide on surgical intervention. With hemorrhage in the cerebellum, the patient also experiences a headache in the occipital region and dizziness. A neurological examination of the patient reveals horizontal gaze paresis in the direction of the hemorrhage with a forced rotation of the eyeballs in the opposite direction and paresis of the abducens (VI) nerve on the affected side.

MRI of the brain of a patient with hemorrhage in the right hemisphere of the cerebellum (indicated by an arrow).

In the acute phase of hemorrhage, the patient may not have signs of damage to the cerebellum or they may be mild. Only sometimes, in patients with hemorrhage in the cerebellum, nystagmus or cerebellar ataxia in the extremities is detected during a neurological examination.

In the eyes of cerebellar hemorrhage, symptoms include spasm of the eyelid muscles (blepharospasm), involuntary closure of one eye, and squinting. Twitching of the eyeballs (ocular bobbing), usually regarded as a symptom of damage to the pons, may appear later when the patient’s consciousness is depressed to the level of coma. The vertical movements of the eyeballs are preserved, and the narrow pupils continue to react to light until the very late stages of the disease. On the affected side, weakness of the facial muscles and a decrease in the corneal (corneal) reflex are often noted.

There is no paralysis of the muscles of the limbs of the opposite half of the body (contralateral hemiplegia) and weakness of the facial muscles. Sometimes, at the onset of hemorrhage in the cerebellum, there is complete paralysis of the muscles of the arms and legs of both sides (tetraplegia) with preservation of consciousness. Sometimes the loss of voluntary movements in a patient manifests itself only in the form of spastic weakness of the muscles of the arms or legs (spastic paraparesis). Plantar reactions (reflexes) first have a flexion character, later - extension. Sometimes, a few hours after a hemorrhage in the cerebellum, the patient suddenly develops stupor and then coma as a result of compression of the brain stem, after which therapeutic measures aimed at reversing the development of the syndrome, and even surgical treatment, are rarely effective.

MRI of the brain of a patient with hemorrhage in the left hemisphere of the cerebellum (indicated by an arrow).

Neurological symptoms from the eyes are important for establishing the location of hemorrhages in the brain:

- with hemorrhages in the shell, the eyeballs deviate in the direction opposite to the side of paralysis

- with hemorrhage in the thalamus, the eyeballs deviate downward and pupillary reactions are lost

- with hemorrhage in the bridge, reflex turns of the eyes to the side are impaired; the pupils, although they react to light, are very weak

- with hemorrhage in the cerebellum, the eyeballs are turned in the direction opposite to the localization of the lesion, in the absence of paralysis

Headache is not considered a mandatory symptom of intracerebral hemorrhage in hypertension. Headache occurs in approximately 50% of patients, while vomiting occurs in almost all. The patient does not necessarily develop depression of consciousness to the point of coma. If the volume of the hematoma is small, the patient's consciousness can be maintained, even if blood has entered the ventricular system.

Epileptic seizures in patients as a result of hemorrhages in hypertension are rare - in less than 10% of cases. In most patients, the correct diagnosis is based on a combination of objective and subjective symptoms.

However, if the patient's consciousness is preserved, it is difficult to distinguish between cerebral infarction (ischemic stroke) and intracerebral hemorrhage. In such cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) of the brain is indicated. Timely use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography of the brain (CT) makes it possible to accurately differentiate the type of lesion and establish their localization, especially in the most difficult to diagnose small hemorrhages in the brain against the background of hypertension in the patient.

Treatment of subdural hemorrhage (acute) non-traumatic

- Maintenance of vital body functions, antihypertensive drugs, analgesics, calcium channel antagonists, dehydration, anticonvulsants.

- Question about surgical evacuation of hemorrhage (removal or stereotactic drainage of the hematoma).

- Secondary prevention.

Treatment is prescribed only after confirmation of the diagnosis by a medical specialist.

Essential drugs

There are contraindications. Specialist consultation is required.

- Mannitol (diuretic, decongestant). Dosage regimen: intravenous, slow stream or drip. Therapeutic dose is 1-1.5 g/kg body weight, prophylactic dose is 0.5 g/kg. The daily dose should not exceed 140-180 g.

- Furosemide (diuretic). Dosage regimen: intramuscularly or intravenously (slow stream) 20-60 mg 1-2 times a day, if necessary, the dose can be increased to 120 mg. The drug is administered for 7-10 days or more, and then the drug is taken orally.

- Ketoprofen (analgesic). Dosage regimen: orally, during meals; tablets 100 mg 3 times a day or 150 mg/day. (retard) with an interval of 12 hours. Capsules - 50 mg in the morning and afternoon, 100 mg in the evening.

- Carbamazepine (anticonvulsant). Dosage regimen: treatment begins with a dose of 0.1 g orally 2 times a day. Then the daily dose is gradually increased by 1/2-1 tablet. to minimally effective (0.4 g per day). It is not recommended to exceed a dose of more than 1200 mg/day.

- Nifedipine (calcium channel blocker, antihypertensive drug). Dosage regimen: intravenous drip, infusion rate should be 0.6-1.2 mg/h; the maximum daily dose is 30 mg, treatment period is 2-3 days. To continue therapy, it is advisable to switch to long-acting oral forms.

Treatment of cerebral hemorrhage in hypertension

Surgical removal of clotted blood in the acute stage of intracerebral hemorrhage is indicated for patients only in rare cases. However, by removing blood clots from a hematoma lying above the tentorium of the cerebellum (supratentorial), it is possible to prevent herniation of the temporal lobe of the brain in comatose patients with still preserved reflex eye movements. Surgical removal of a hematoma from the focus of acute hemorrhage in the cerebellum is usually the method of choice, as it often saves the patient’s life and gives an excellent prognosis in terms of restoration of impaired functions.

If the patient has a clear consciousness and there are no symptoms of focal damage to the brain stem, then if he has a small cerebellar hematoma, the neurosurgeon may refuse immediate surgical intervention to remove it. However, it is necessary to remember the likelihood of rapid deterioration of the clinical condition when the hematoma is localized in the cerebellum. Therefore, in such patients there should always be the possibility of urgent surgery if clinical need arises.

To reduce cerebral edema around intracerebral hemorrhage, mannitol and other osmotic diuretics are prescribed. The activity of steroids in intracerebral hematoma is insignificant. Monitoring intracranial pressure can help evaluate the effectiveness of drug therapy and avoid significant deviations in the direction of arterial hypo- and hypertension. A sharp decrease in blood pressure in order to “stop bleeding” during intracerebral hemorrhage is ineffective, since most often stopping the bleeding that has occurred during intracranial hemorrhages occurs spontaneously even before examining patients.

In conditions such as toxicosis of pregnancy and malignant arterial hypertension, early diagnosis and prudent treatment are especially necessary. This is necessary in order to avoid an excessive or sudden decrease in blood pressure in the patient.

Classification of intracerebral intraventricular hemorrhage

There are three main types of disease based on the site of blood penetration:

- under the lining of the ventricles (subependymal);

- into the lateral ventricles;

- into the ventricles and brain matter.

Also, depending on the location, the hemorrhage can be in the lateral or third, fourth ventricles of the brain. If blood gets into the lateral cavities, then after they are filled it can move into the third, then into the fourth ventricle. Such massive bleeding leads to a significant increase in cerebral volume and has extremely unfavorable consequences; an isolated breakthrough into the lateral cavities is less dangerous.

Depending on the degree of blood filling, four stages of disease progression are distinguished:

- Blood is found only under the ependyma (lining).

- Half filled, no cavity expansion.

- More than 50% filling with lumen expansion.

- In addition to complete filling of the ventricle, there is damage to the surrounding nervous tissue (parenchymal bleeding).