11.09.2017

Cardioembolic stroke is a common form of cerebral circulatory disorder. A third of all ischemic strokes develop due to cardiogenic embolism. The disease occurs as a result of blockage of the arteries that supply the brain by cardiac emboli, which leads to dysfunction of the cerebral circulation. The reasons for the phenomenon can be varied. In medicine, there are about 20 probable causes that provoke the development of pathology.

And their number continues to increase. Embolic stroke develops quickly due to physical or mental stress. And the clinical picture of the disease is expressed already at the initial stage of development of the pathological process. What is the cardioembolic type of ischemic stroke, what symptoms does it manifest, what danger does it pose to the health and life of the patient?

Historical reference

Back in the 18th century. scientists presented a hypothesis about the relationship between heart disease and ischemic stroke. Rudolf Virchow made a great contribution to understanding the pathogenesis of the latter. In 1847, with the help of a series of studies, he was able to prove that thrombosis is not a cause, but a consequence of embolism and atherosclerosis.

Virchow's ideas gradually entered world medical practice. At the beginning of the last century, scientists believed that up to 7% of all stroke cases have a cardioembolic etiology. Today this figure has increased to 40%. The study of pathology continues by specialists in this field.

Development mechanism

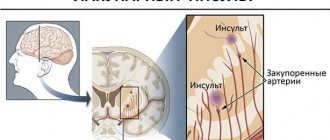

Ischemic stroke of cardioembolic origin occurs due to the formation of blood clots in the heart. Over time, they transform into blood clots or emboli.

The formation of a blood clot occurs due to damage to the endocardium. It represents the inner layer lining the heart muscle. A protein film is formed on its surface, which is otherwise called a fibrous membrane. Platelets, fibrin and leukocytes gradually join it. The thrombus increases in size, its structure is loosened and compacted by salts. If it or some part of it comes off, then this violation is already an embolus.

The manifestations of the unpleasant consequences of cardioembolic stroke depend solely on the location of the lesion. Moving into the brain, emboli travel through the bloodstream, which already has pathological changes. They manifest themselves in heart valve defects. After reaching the final goal, the clot clogs a separate section of the blood flow.

Mobile emboli can travel through the smallest arteries. At the site of blockage and cessation of blood circulation, new blood clots gradually form. Depending on the location of the lesion, corresponding symptoms occur.

Risk factors

Ischemic stroke of cardioembolic origin occurs due to blockage of cerebral arteries by emboli. They begin their formation in the heart. Under the influence of negative factors, they come off and, together with the blood flow, enter directly into the brain. As a result, the affected structures experience a deficiency of oxygen and nutrients necessary for full functioning. Therefore, cell death occurs with simultaneous damage to elements of the nervous system.

The following disorders can provoke the appearance of blood clots:

- high blood pressure;

- vascular atherosclerosis;

- progressive diabetes mellitus;

- chronic form of heart failure;

- cardiac aneurysm;

- vascular implants.

People who abuse alcohol and smoke are at risk. The likelihood of developing a stroke increases with age. People over 65 years of age who lead a sedentary lifestyle are also susceptible to this pathology. Stroke of cardioembolic etiology is especially common in patients suffering from cardiovascular disorders.

Main reasons

Cardioembolic ischemic stroke occurs in diseases of the cardiovascular system. The main causes of blockage of cerebral vessels by blood clots include the following factors:

- increased thrombus formation;

- myocardial infarction, the presence of a parietal thrombus inside the heart;

- defects of the septum between the ventricles or atria;

- heart valve defects (stenosis, calcification, incomplete closure of the valves, prolapse, changes after injury, surgery);

- turbulence in the atrium;

- aneurysm (dissection) of the wall between the atria;

- the presence of an unclosed oval hole in the heart;

- tachycardia of unknown origin;

- endocarditis (inflammation of the inner lining of the heart) of rheumatoid nature;

- atrial fibrillation;

- cardiomyopathy (pathological change in the structure and function of the myocardium);

- akinesia (lack of activity) of the ventricle;

- acute heart failure;

- heart tumors (atrial myxoma);

- heart injury due to bruise.

There are risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing embolic stroke. These include the following provisions:

- the presence of an artificial valve in the heart;

- bacterial endocarditis;

- hypertension;

- diabetes;

- atherosclerosis;

- chronic heart failure;

- old age from 60 years.

Classification of cardiac sources

In modern medical practice, up to 20 sources are distinguished that lead to the development of pathology. They can be divided into 2 conditional groups: those provoked by disturbances in the functioning of the chambers of the heart and those caused by defects of the heart valves.

The first includes the following disorders:

- acute myocardial infarction;

- atrial fibrillation of permanent and paroxysmal etiology (up to 60% of cases of cardioembolic stroke are caused by this cause);

- post-infarction cardiosclerosis;

- cardiac aneurysms;

- neoplasms in the muscle cavity.

The second group includes the following problems:

- aortic stenosis;

- the presence of artificial valves;

- mitral valve prolapse;

- calcification

The greatest danger comes from sources of pathology caused by disturbances in the functioning of the chambers of the heart. They are characterized by the development of a large number of microembolic signals (MES), which lead to stroke. They depend on the structure and density of emboli, and not on their size.

Atrial fibrillation and CES

Atrial fibrillation, or atrial fibrillation, is the most common cause of ischemic stroke of cardioembolic origin. With this pathology, the formation of a blood clot most often occurs in the right atrium. Echocardiography is used to identify the problem.

Paroxysmal and permanent types of arrhythmia carry the same consequences. However, in the first case they may be more dangerous for the patient. The attack of the disease begins suddenly. After sinus rhythm normalizes, the formed blood clot can break off and travel through the bloodstream to the brain.

Valve damage and CEI

Complications in the form of cardioembolic stroke can occur against the background of valvular abnormalities. A similar etiology of the disorder is recorded in 10% of patients.

Another cause of stroke is implanted artificial valves. This risk is possible in 1-2% of cases. If biomaterial was used during the prosthetic procedure, the likelihood of complications occurring is much lower.

Calcification of aortic stenosis, foramen ovale, left atrial myxoma and CES

The presence of a patent foramen ovale can provoke a cardioembolic stroke. However, this reason is not common and typical. With large sizes of the oval window, the risk of developing pathology increases in direct proportion.

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and CES

According to medical statistics, acute myocardial infarction leads to stroke in 2% of cases. This is due to the use of anticoagulants during the treatment of the underlying disorder.

Prognosis and prevention of cardioembolic stroke in atrial fibrillation

V.A. PARFENOV

, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor,

S.V.

VERBITSKAYA ,

First Moscow State Medical University named after. THEM. Sechenov A review of the literature on the prediction and prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation (AF) is presented.

It is noted that the easy-to-use CHA2DS2-VASc scale can well predict the risk of stroke in AF. In patients with one or more risk factors for stroke according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scale, the use of oral anticoagulants is recommended. Data from large randomized trials are presented that show that new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) are not inferior to warfarin or have the advantage of a more significant reduction in the risk of stroke and a less significant risk of major, especially intracranial, bleeding. There has been positive practical experience with the use of dabigatran (Pradaxa®) at a dose of 150 mg or 110 mg twice in patients with AF. In our country, the introduction into neurological practice of new anticoagulants, the use of which does not require control using the international normalizing ratio, will make it possible to more widely prescribe anticoagulant therapy to patients with AF and reduce the incidence of cardioembolic stroke. Atrial fibrillation (AF, atrial fibrillation) is one of the most common heart rhythm disorders;

its frequency increases with age; in people over 70 years of age, AF occurs in approximately 5% of cases [1, 2]. Persistent and paroxysmal form of non-valvular AF is one of the most important risk factors for ischemic stroke (IS), increasing the likelihood of its development by 3-4 times [1]. In patients with AF, a slowdown in blood flow occurs, leading to the formation of blood clots mainly in the left atrial appendage, which can cause embolism in the blood vessels of the brain and other organs. Predicting the risk of stroke in atrial fibrillation. In patients with AF, the risk of stroke increases with increasing age, in the presence of heart failure, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, previous episodes of thromboembolism, mitral valve calcification, or thrombus in the left atrium [2]. In clinical practice, the CHADS2 scale has been used for a long time as the main scale to predict and assess the risk of thromboembolic complications in patients with AF, among whom AI is of leading importance. The abbreviation CHADS2 comes from the first letters of the English names of individual risk factors for stroke: Congestive heart failure - chronic heart failure, Hypertension - arterial hypertension, Age - age over 75 years, Diabetes mellitus - diabetes mellitus, Stroke - AI or transient ischemic attack (TIA) in medical history. In this scale, 2 points are assigned to stroke or TIA (therefore, an index of 2 is assigned next to the letter “S”) and 1 point to the remaining factors (Table 1). The higher the CHADS2 score, the higher the risk of stroke, and vice versa (Table 2). In recent years, the CHA2DS2-VASc scale [3], which is an extension of the CHADS2 scale to which other independent risk factors for IS have been added, has been proposed and widely introduced into clinical practice (Table 3). In this scale (in addition to the CHADS2 scale), the following vascular risk factors are used: vascular damage (history of myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial atherosclerosis, aortic atherosclerosis), age 65-74 years, female gender. If the maximum number of points on the CHADS2 scale is 6, then on the CHA2DS2-VASc scale it is 9. In 2010, the CHA2DS2-VASc scale was included in the recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology [4] for assessing the risk of IS in AF. The CHA2DS2-VASc scale includes more factors that determine the risk of stroke, its superiority over the CHADS2 scale has been confirmed in several clinical studies, among which a recent large study that included data on 73,538 patients with AF who did not receive anticoagulant therapy is particularly noteworthy [5]. During a year of observation in individuals with “low risk” (score = 0), the frequency of systemic thromboembolic complications according to the CHADS2 scale was 1.67 per hundred patients per year, and according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scale - 0.78. The data obtained demonstrate that patients who were classified as low risk according to the CHA2DS2VASc scale had a truly low risk of developing thromboembolic complications. Analysis of the results of observation of this large group of patients over 10 years shows a significantly higher information content of the CHA2DS2-VASc scale in comparison with the CHADS2 scale. Many patients from the so-called. low-risk groups according to the CHADS2 scale have a fairly high risk of thromboembolic complications. Overall, the CHA2DS2-VASc score is better at predicting stroke risk (Table 4) than the CHADS2 score. Prevention of cardioembolic stroke

To prevent stroke and other thromboembolic complications (systemic embolism) in AF, until recently, the use of aspirin or indirect anticoagulants (warfarin) under the control of the international normalized ratio (INR) was recommended [6-9].

For patients with AF under 75 years of age who had no history of stroke and a low risk of developing it (less than 2% per year), aspirin was recommended at a dose of 75-325 mg per day. With a higher risk of stroke in patients with AF (4% per year or more), the prescription of warfarin (with a target INR of 2-3) was considered justified in the absence of contraindications to its use [6, 7]. A meta-analysis of several studies showed that the use of warfarin in AF reduces the risk of stroke by an average of 68% [10]. During the year, treatment with warfarin in 1 thousand patients with AF prevents the development of 31 IS. Major bleeding occurs relatively rarely in 1.3% of cases (in the placebo or aspirin group in 1% of cases) if the INR is maintained in the therapeutic range of 2 to 3. When treating with warfarin, it is necessary to remember its possible interaction with other drugs and foods, the need for regular laboratory monitoring of INR and, on this basis, dose adjustment of the drug. The effectiveness of aspirin in AF is much lower; it reduces the risk of stroke by an average of 21% in patients with AF. The widespread use of warfarin in our country is limited to a certain extent by the fact that many patients who have undergone IS due to AF refuse treatment with the drug due to the need to regularly visit the clinic to monitor the INR and limit the intake of certain foods and drugs. During follow-up (an average of more than 4 years) of 77 patients who underwent IS due to AF, only 21 patients (27.2%) began to regularly take warfarin and achieved an INR of 2 to 3 [11]. In arterial hypertension, its effective treatment with normalization of blood pressure (BP) reduces the risk of both stroke and bleeding when taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents [5]. In approximately one third of patients who have suffered an IS or TIA due to AF, another possible cause of IS is found, for example, significant stenosis of the internal carotid artery. In such cases, combination therapy is possible, for example, carotid endarterectomy and subsequent treatment with anticoagulants. When treating with antithrombotic drugs, it is necessary to take into account the risk of bleeding, especially intracranial bleeding, which often leads to the death of the patient. The risk of bleeding should be assessed before prescribing anticoagulant therapy in patients with AF. In clinical practice, the HAS-BLED scale is used to assess the risk of bleeding [12], which is included in modern recommendations for the treatment of AF (Table 5). Currently, the effectiveness of new oral anticoagulants that affect other stages of blood coagulation (Fig. 1) and do not require constant monitoring of the INR, as with warfarin treatment, is being actively studied in patients suffering from AF. The results of several large randomized trials have shown that new indirect anticoagulants are not inferior to warfarin or even superior to it in preventing stroke, while being characterized by a lower risk of bleeding, especially intracranial. The first of this group of drugs to prove its effectiveness was dabigatran etexilate (dabigatran), which is currently widely used throughout the world for the prevention of stroke in AF. Dabigatran in the prevention of stroke

Dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor, the effectiveness and safety of which in the prevention of stroke and thromboembolic complications in patients with AF compared with warfarin was studied in the RE-LY study [13].

The study included patients with AF who had at least one or more risk factors for stroke and systemic embolism: history of stroke or TIA, left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%, heart failure NYHA class 2 or higher (within 6 months . and more), age 75 years and older, or age 65 years and older in combination with arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus or coronary heart disease. Exclusion criteria for participation in the study were: severe heart valve pathology, the presence of a prosthetic heart valve, ischemic stroke within 14 days before inclusion in the study, severe stroke within 6 months. before inclusion in the study, severe disability due to stroke, high risk of bleeding, creatinine clearance less than 30 ml/min, active liver disease, pregnancy. The primary objective of the study was to compare the incidence of stroke and systemic embolism while taking dabigatran at a dose of 110 or 150 mg twice daily or warfarin at a dose that maintains an INR of 2 to 3. The primary safety endpoint was the incidence of major bleeding at various treatment regimens according to the frequency of life-threatening hemorrhages. The study included 18,113 patients at 967 centers in 44 countries. The study design involved randomization of patients into three groups: two groups received the study drug dabigatran etexilate at a dose of 150 mg or 110 mg twice a day, in the third group patients received the comparison drug warfarin. The groups were homogeneous in size and did not differ from each other in basic clinical characteristics, some of which are shown in Table 6. During an average of two years of observation, major vascular events (stroke, systemic embolism) developed significantly less frequently in the group of patients taking dabigatran 150 mg twice daily (1.11% per year) than in the group of patients receiving warfarin (1.71% per year). In the group of patients receiving dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, the rate of stroke and embolic events was 1.54% per year, which was comparable to the rate of events in the warfarin group. Mortality (from all causes) at one year was 4.13% in the warfarin group and trended lower in the dabigatran 110 mg group (3.75%) and in the dabigatran 150 mg group (3.64%). Mortality from cardiovascular diseases during the year was 2.69% in the warfarin group, it tended to decrease (2.43%) in the dabigatran 110 mg group and was significantly lower (2.28%) in the dabigatran 150 mg group. The incidence of major bleeding during the year during warfarin therapy was 3.36%, tended to decrease in the dabigatran 150 mg group (3.11%) and was significantly lower (2.71%) in the dabigatran 110 mg group. The incidence of life-threatening bleeding within a year was 1.24% in the group of patients taking dabigatran 110 mg twice a day, 1.49% in the group receiving dabigatran 150 mg twice a day, and was significantly higher (1.85% ) in the warfarin group. The incidence of hemorrhagic stroke within a year was 0.12% in the dabigatran 110 mg group, 0.10% in the dabigatran 150 mg group and was significantly higher (0.38%) during warfarin therapy. The main adverse events during the entire treatment period are presented in Table 7, which shows that there were no significant differences between the groups in the main adverse events, with the exception of dyspepsia, which was slightly higher in the group of patients taking dabigatran. Among the patients participating in the study, almost every fifth suffered a stroke or TIA; using randomization, these patients, along with the rest, were divided into three main groups; Thus, 1,195 patients took dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, 1,233 took dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, 1,195 patients took warfarin. In the subgroup of patients with a history of stroke or TIA, the incidence of stroke and systemic embolism per year was 2.38%, which was significantly more common than in patients without a history of stroke or TIA - 1.22%. Analysis of the study results in this subgroup of patients showed that the main patterns observed in the entire group of patients are preserved; There was no effect of previous stroke or TIA on the main differences noted between the groups of patients receiving dabigatran or warfarin therapy [15]. In patients who had a stroke or TIA, there was a trend towards a lower incidence of major events (stroke, systemic embolism) with dabigatran compared with warfarin, but the incidence was significantly lower with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily (Table 1). 8). In patients who had a stroke or TIA, there was a significant reduction in the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke when taking dabigatran compared to treatment with warfarin, with the greatest benefit in reducing the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke observed in the dabigatran 110 mg twice daily group (Table 9). The incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was also higher in the subgroup of patients taking warfarin. The incidence of all strokes tended to be higher in the subgroup of patients receiving warfarin, due to a higher incidence of hemorrhagic stroke. In a subgroup of patients who had a stroke or TIA, treatment with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was associated with a reduction in the incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, as well as a reduction in the incidence of life-threatening bleeding compared with warfarin. The incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was comparable in the subgroups of patients taking dabigatran 110 mg twice daily or warfarin. In patients receiving dabigatran therapy at a dose of 150 mg 2 times a day, gastrointestinal bleeding occurred more often than in the warfarin group. The incidence of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly between patients who had a stroke or TIA depending on the therapeutic regimens. Rivaroxaban in stroke prevention

Rivaroxaban (a direct factor Xa inhibitor) at a dose of 20 mg or 15 mg (in patients with creatinine clearance 30-50 ml/min) per day was studied in patients with non-valvular AF compared with warfarin in the ROCKET AF study [ 14].

The study included AF patients with moderate and high risk of stroke; more than half of the patients suffered a TIA or stroke or an episode of systemic embolism. The study included 14,264 patients (60% men, 40% women, mean age 73 years), with a mean follow-up of 707 days. The primary endpoint of the study was the incidence of major vascular events (IS, hemorrhagic stroke, systemic embolism) in patients taking rivaroxaban or warfarin. The safety of treatment was assessed by the incidence of clinically significant hemorrhagic events. The study found that major vascular events occurred at a rate of 1.7% per year in patients receiving rivaroxaban and 2.2% per year in patients receiving warfarin (p < 0.001). Clinically significant hemorrhage occurred at an incidence of 14.9% per year in patients taking rivaroxaban and 14.5% per year in patients taking warfarin (p = 0.44). In the group of patients taking rivaroxaban, intracranial hemorrhages (0.5%; in the warfarin group - 0.7%, p = 0.02) and fatal hemorrhages (0.2%; in the warfarin group - 0.5) were less likely to develop. %, p = 0.003). In the subgroup of patients who did not have a history of TIA, stroke, or episodes of systemic embolism, the incidence of major events was 2.57% when taking rivaroxaban and 3.61% in the warfarin group, which proves the superiority of rivaroxaban over warfarin in the primary prevention of stroke, TIA and systemic embolism. In this subgroup, clinically significant hemorrhages occurred less frequently (1.67%) with rivaroxaban than with warfarin (2.86%). In the subgroup of patients with a history of IS, TIA, or an episode of systemic embolism, the incidence of major events was not significantly different and reached 4.8% and 4.9%, respectively, when using rivaroxaban and warfarin, respectively. In this subgroup, clinically significant hemorrhages occurred with a frequency of 3.5% when using rivaroxaban and 3.9% when taking warfarin. Apixaban in stroke prevention

Apixaban (a direct factor Xa inhibitor) was studied for the prevention of thromboembolic events in patients with non-valvular AF in the AVERROES [15] and ARISTOTLE [16] studies.

The AVERROES trial [15] examined the effectiveness of apixaban and aspirin in 5,599 patients (mean age 70 years, 41% women and 59% men) with non-valvular AF and one or more additional risk factors for stroke (median CHADS2 score 2 points). , for whom it was impossible to prescribe warfarin therapy for a number of reasons. Apixban was used at a dose of 5 mg 2 times a day (in 94% of cases) or 2.5 mg 2 times a day (in 6% of cases in patients satisfying 2 or more of the following criteria: age 80 years and older, weight 60 kg And less, the level of creatinine is 133 mmol/l and more). Aspirin was used at a dose of 81-324 mg per day. The study was discontinued ahead of schedule, because convincing evidence of the superiority of Apixaban over aspirin was obtained. The frequency of a stroke or system embolism in a group of patients taking Apixaban was 1.6% per year, which was significantly lower than in the Aspirin group, in which it reached 3.7% per year. Apixban was reliably more effective than aspirin in the prevention of severe and fatal stroke, the frequency of which was 1% in the Apixaban group and 2.3% per year in the Aspirin group. The frequency of clinically significant bleeding did not differ significantly in treatment groups and amounted to 1.4% per year in the Apixaban group and 1.2% per year in the Aspirin group. In a small group of patients who suffered AI or TIA, the frequency of development of re -AI or system embolism was 2.5% in patients in the Apixban group and significantly more - 8.3% in the Aspirin group. At the same time, the frequency of development of clinically significant bleeding did not differ significantly and amounted to 3.5% per year in the Apixbana group and 2.7% per year in the Aspirin group. The study of Aristotle [16] compared the effectiveness of Apixaban and Warfarin in the prevention of stroke or system embolism in 18 201 patients (average age 70 years, 35% of women, 65% of men) with at least one additional risk factor for stroke. Apixban was used in dosages of 5 mg or 2.5 mg (in patients with creatinine clearance of 30-50 ml/min) 2 times a day, warfarin in doses necessary to achieve many 2.0-3.0. The average monitoring time of patients was about 2 years. The frequency of stroke or system embolism was 1.27% in the Apixban group, which was significantly lower than in the warfarin group - 1.6%. In the Apixbana group, the frequency of development of hemorrhagic stroke (by 49%) and to a lesser extent (8%) frequency of AI or an unspecified stroke has significantly decreased. The frequency of deaths in the Apixbana group was 3.52% per year, in the warfarin group, 3.94% are significantly higher (p = 0.047). The frequency of development of serious bleeding was 2.13% in the Apixban group and was significantly higher - 3.09% in the warfarin group (p <0.001). The advantage of Apixban over warfarin was also noted in a group of patients who suffered TIA or AI. The modern approach to the prevention of stroke

on the basis of the results of recent studies is given recommendations [4] on the prevention of stroke and other thromboembolic complications in patients with FP using the Cha2DS2-VASC scale (Table 10).

As can be seen from the data presented in the table, oral anticoagulants are recommended for patients with one or more points on the Cha2DS2-VASC scale. Among the new oral anticoagulants, Dabigatran (Pradax) is currently most widely used. In the treatment of dabigatrane - unlike warfarin - there is no need to select a dose of the drug, regular laboratory (hematological) control, restrictions on taking many food products and drugs, which improves the quality of life of patients with FP [16]. Dabigatran is prescribed in a fixed dose of 150 mg or 110 mg twice a day. If necessary, laboratory (hematological) control of Dabigatran, partially activated thromboplastic time, thrombin time and other indicators of the coagulogram can be used [17]. When choosing a dose of dabigatran (110 mg or 150 mg twice a day), in each case, it should be based on the possible risk of developing AI, system embolism and bleeding. Dabigatran at a dose of 150 mg twice a day has an advantage in the prevention of the development of AI and system embolism compared with warfarin, at a dose of 110 mg twice a day is characterized by a lower frequency of bleeding of various localization, including intracranial ones. In most cases, FP requires a more reliable prevention of stroke and system embolism, therefore, the purpose of Dabigatran at a dose of 150 mg twice a day is preferable. However, in some patients with a high risk of bleeding, it is advisable to use a dose of 110 mg twice a day. Currently, only a large dose (150 mg twice a day) of Dabigatran is recommended for the prevention of a stroke in FP in the United States [18]. The conducted quantitative analysis of all possible advantages and disadvantages of different doses of Dabigatran demonstrates the advantage of a large dose [19]. One of the questions to which the answer was not received during the Re-Ly study concerns the time for the appointment of Dabigatran in patients with FP who suffered AI or TIA. Is it possible to appoint Dabigatran in the earliest period after the development of AI or TIA, which is advisable in most cases? Re-Ly study included patients who suffered a stroke or TIA, only after 2 weeks. From the moment of the disease, therefore, the question of the appointment of Dabigatran in the period is up to 2 weeks. After AI and Tia, it remains discussion and requires further research in this direction. The advantage of treating dabigatrane and other new oral anticoagulants over warfarin is of particular importance in cases where patients live in regions where varfarin laboratory control is poorly established [20, 21]. Unfortunately, in our country, neurologists, when conducting patients who suffered AI or TIA against the background of FP, often face significant problems due to the lack of a established laboratory service necessary for monitoring the INR when prescribing therapy with warfarin [22]. Therefore, the use of new oral anticoagulants, the treatment of which does not require a dose, regular laboratory control, will allow neurologists to more effectively carry out secondary prevention of cardiembolic stroke in patients with non -laid FP. Currently, it is proved that the use of a simple risk scale for the development of a stroke CH2DS2-VASC allows us to predict the likelihood of thromboembolic events in patients with FP. In patients with one or more risk factors on the CHA2DS2-VASC scale, it is recommended to use warfarin or new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, Apixaban). Currently, the positive world practical experience of using Dabigatran in doses of 110 mg or 150 mg is accumulated twice a day in order to prevent stroke, system emboli and a decrease in cardiovascular mortality. In our country, a significant part of the patients who suffered AI or TIA against the background of the FP does not accept warfarin due to the complexity of the regular control of the IS. The introduction of new anticoagulants into the neurological practice, the use of which does not require the control of the IN, will allow more widely prescribing anticoagulant therapy for patients with FP and reduce the frequency of cardiembolic stroke. Literature

1. Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial Fibrillance As an Independent Risk Factor for Stroke: The Framingham Study. Stroke, 1991; 22: 983-988. 2. Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group. Independent Predictors of Stroke in Attrial Fibrillaration: A Systematic Review. Neurology, 2007; 69: 546-554. 3. Lip Gy, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane Da, Crijns HJ. Refining Clinical Risk Stratification for Predicting Stroke and Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation Assing ANVEL RISK FACTOR-BASED APPROCH Ion. Chest, 2010; 137: 263-272. 4. European Heart Rhythm Association; European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Camm Aj, Kirchhof P, Lip Gy et al. Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillaration: The Task Force for the Management of the Atrial Fibrillaration of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). EUR Heart J., 2010; 31: 2369-2429. 5. Olesen JB, Lip Gy, Hansen Ml et al. Validation of Risk Stratification Schemes for Predicting Stroke and Thromboembolism in Patients with Atrial Fibrillance: Nationalwide Cohort Study. BMJ, 2011; 342: D124. 6. Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G et al. Guidelines for Prevention of Stroke in Patth Ischemic Stroke or Transent Ischemic Attack: Astatement for Healthcare Professionals From Themican Health Troke Association Council on Stroke: Co-Sponsored by the Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: The American Academy of Neurology Affirms The Value of this Guideline. Stroke, 2006; 37: 577-617. 7. European Stroke Organising (ESO) Executive Committee; ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for Management of Ischaemic Stroke and Transent Ischaemic Attack. Cerebrovascus dis., 2008; 25: 457-507. 8. Suslina Z.A., Fonyakin A.V., Geraskina L.A. and others. Practical cardiourology. M., Ima Press, 2010.-304 p. 9. Furie Kl, Kasner Se, Adams Rj et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke or Transent Ischemic Auttack a Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the America Heart Association/American Stroke Strokan Strokan Stroke Strokan Stroke Strokan Stroke Strokan Stroke Strokan Stroke Strokan Stroke Stroke Strokan Stroke Strokan Stroke Strokan Stroke Strokan Stroke Stroke Strokan Stroke Stroke Stroke Stroke Strokan Stroke Stroke Strokan Stroke Sociation. Stroke, 2011; 42: 227-276. 10. RISK FACTORS For Stroke and Efficacy of Antithrombotic Therapy in Attrial Fibrillaration: Analysis of Pooled From Five Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch Intern Med., 1994; 154: 1449-1457. 11. Verbitskaya S.V., Parfenov V.A. Secondary prophylaxis of stroke on an outpatient basis. Neurological journal, 2011; 1: 17-21. 12. Pisters R, Lane Da, Nieuwlaat R et al. .A Novel User-Friedly Score (Has-Bled) To Assess 1-Year Risk of Major Bleeding in Patyl Fibrration: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest, 2010; 138: 1093-1100. 13. Connollly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S et al. Dabigatran Versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillaration. N English J Med, 2009; 361: 1139-1151. 14. Patel Mr, Mahaffey Kw, Garg J Et Al. Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillaration. N English j med., 2011; 365: 883-891. 15. Connollly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C et al. Apixaban in Patients with Atrial Fibrillance. N English j med., 2011; 364: 806-817. 16. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ et al. Apixaban Versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N English j med., 2011; 365: 981-992. 17. Van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haerter S et al. Dabigatran EteXilate-a Novel, Reversible, Oral Direct Thrombin Inhibitor: Interpretation of Coagulation Assays and Reversal of AntiCoagulant Activity. Thromb Haemost, 2010; 103: 1116-1127. 18. Beasley BN, UNGER EF, TEMPLE R. Anticoagulant Options-Why The FDA Approved a Higher But not A Lower Dose of Dabigatran. N English J Med, 2011; 364: 1788-1790. 19. Pink J, Lane S, PirmohaMed M, Hughes da. Dabigatran EteXilate Versus Warfarin in Management of Non-Valvular Attrial Fibrillaration in Uk Context: Quantitate Benefit-Harm and Economic Analyses. BMJ, 2011; 343: D6333. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.d6333. 20. Kamel H, Johnston SC, Easton JD, Kim as. Cost-Effectivence of Dabigatran Compared with Warfarin for Stroke Proveement in Patience with Atrial Fibrillaration and Prior Stroke Transent Ischemic Attack. Stroke, 2012; 43: 881-883. 21. Harris K, Mant J. Potential Impact of New Oral Anticoagulants on the Management of Atrial Fibrration Stroke in Primary Care. Int J Clin Pract., 2013; 67: 647-655. 22. Parfenov V.A., Khasanova D.R. Ischemic stroke. M., MIA, 2012. - 288 p.

Diagnostics

Any type of stroke threatens the patient’s life. Therefore, only after confirming the diagnosis and determining its cause, treatment tactics are selected. For this purpose, the patient is prescribed a comprehensive examination, which consists of the following activities:

- Ultrasound to detect pathologies of the heart muscle;

- ECG recording using the Holter method (allows you to determine the relationship between pressure surges and angina attacks);

- MRI and CT;

- examination of the heart using a transesophageal ultrasound probe.

Particular attention is paid to the patient's medical history and previous cardiac diseases.

Diagnostic principles

Diagnosis of cardioembolic stroke involves comparison with 3 criteria:

- the presence of cardiac damage with the possibility of embolism;

- causeless appearance of signs of a neurological disorder;

- suspected systemic embolism.

The presence of 3 criteria simultaneously allows you to confirm the preliminary diagnosis.

Current forecast

The survival rate for this form of the disease is influenced by various factors: the degree of brain damage, the spread of areas of necrosis, the presence of paralysis, the age of the patient, the time elapsed from the onset of the acute stage to seeking medical help, the quality of treatment and rehabilitation.

There is a direct relationship between the mortality rate and the patient's age. The lowest number of deaths is observed in the age group up to 70 years, then the increase is exponential.

If a patient's cerebral vessel thrombosis does not affect the area that controls vital functions, his chances of survival are significantly increased. Careful adherence to medical recommendations, the use of a variety of treatment and recovery methods help the patient cope with the problem and maintain a normal quality of life.

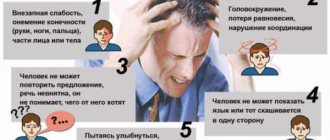

Symptoms of ischemic stroke of cardioembolic origin

Cardioembolic stroke always occurs suddenly. Its manifestations depend on the location of the lesion, the parameters of the embolus and its etiology. Most often, a stroke originates in the middle cerebral artery.

Clinical signs occur within 5 minutes after the onset of the attack and are characterized by:

- disturbance of consciousness;

- convulsive seizures;

- paralysis;

- speech disorders;

- deterioration of vision.

When parts of the right hemisphere are damaged, a person loses orientation in space. He develops problems with color perception and his psycho-emotional background deteriorates. When neurons die in the left hemisphere of the brain, speech dysfunction develops. Memory suffers, the patient cannot remember the names of objects from the environment.

The listed symptoms pose a threat to human life. Only timely implementation of therapeutic measures can minimize the risk of complications. Therefore, when an attack begins, it is necessary to immediately call a team of medical workers.

Therapeutic measures

Therapy begins in the first hours after the onset of an attack. It is important to remember that the prognosis and severity of consequences depend on the timeliness of assistance provided.

Patients are prescribed:

- thrombolytics (Urokinase, Fibrinolysin) for resorption of formed blood clots;

- anticoagulants (Warfarin, Heparin), which reduce blood density and prevent recurrent thrombus formation;

- neuroprotectors (Nootropil) and antioxidants (Glycine, Mexidol) to reduce possible damage to brain cells;

- vasoactive agents (Actovegin, Cinnarizine) to improve cellular metabolism.

Regardless of which areas of the brain are affected, clinical stroke is almost always accompanied by arterial hypertension. To reduce and stabilize blood pressure, fast-acting drugs (Captopril, Clonidine) and long-term medications are used to prevent the development of crises (Lisinopril, Prestarium).

In the first days after an ischemic stroke in the left MCA or in other areas, the patient is provided with rest to prevent cerebral edema and prevent a recurrent ischemic attack.

After the person’s condition becomes stable, he is transferred to the general ward and, while continuing drug therapy, rehabilitation measures to restore impaired functions begin.

Treatment

Stroke therapy requires an integrated approach. It is based on antithrombic drugs. With their help, it is possible to influence the main pathogenetic link. These medications are also used for secondary prevention in order to reduce the consequences of pathology.

Taking specific medications is a small part of therapy. Doctors recommend that all patients with CES radically reconsider their lifestyle and follow a diet with a reduced amount of salt.

Therapeutic algorithm for CEI

The basis of therapy for CES is the following medications:

- Immediately after the attack, drugs with thrombolytic effects are administered.

- Reopoliglucin is a solution to improve blood flow.

- Medicines to normalize blood pressure.

- Neuroprotectors that help improve the condition of nerve elements.

During prolonged bed rest, it is mandatory to take antibacterial drugs to prevent infectious processes in the lungs and kidneys.

Features of antithrombic therapy after CES

This therapy involves the use of anticoagulants in tablet form. Warfarin is preferred. Patients with arrhythmia and rheumatic lesions of the heart muscle are prescribed long-term treatment. In case of myocardial infarction, its duration is up to 6 months.

If anticoagulants are intolerant or side effects occur, stop taking them. If CES is accompanied by high blood pressure, the prescription of antihypertensive medications is mandatory.

Throughout the course of antithrombic therapy, patients with diabetes should undergo sugar tests and monitor lipid metabolism.

Additionally, the help of neuroprotectors may be required. They influence the pathogenetic basis of stroke, and at different stages of its development. For this purpose, Citicoline is most often prescribed.

The duration of the recovery period is determined by the severity of the stroke, the location of the lesion and the severity of symptoms. The standard rehabilitation course ranges from 6 months to 4 years. During this period, not only specific medications are prescribed, but also therapeutic massage and special gymnastics.

To normalize fine motor skills, kinesiotherapy is used. A stay at a sanatorium-resort also has a positive therapeutic effect.

Recommendations for patients

There is a high probability of recurrent cardioembolic stroke, so the patient must follow doctor's instructions. The patient must adhere to a strict diet.

It is recommended to exclude the following foods from your daily diet:

- Spicy seasonings.

- High fat foods.

- Pickled vegetables.

- Smoked meats.

The patient needs to monitor blood sugar and cholesterol levels. He must take blood thinners for the rest of his life. The patient must regularly visit a neurologist and cardiologist. You can get a referral for a consultation with a specialist from a therapist at a free clinic.

The duration of the rehabilitation period varies from three months to several years. The patient needs to engage in physical therapy and attend kinesiotherapy sessions. Kinesitherapy can be active or passive. During passive kinesitherapy sessions, special devices are used that imitate simple physiological movements. Active kinesitherapy includes such healing techniques as yoga and qigong.

Forecast

The death of essential brain cells is a complex pathology. It is always accompanied by striking clinical manifestations, as a result of which the patient is assigned a disability group. The prognosis for CES depends on the area of the lesion and the presence of other health problems. Most of the time it is disappointing.

If you seek medical help in a timely manner, a dramatic improvement in your condition occurs within 10 days after the start of treatment. Over the next year, survival is observed in 80% of cases.

Symptoms of the disease

In most cases, cardioembolic stroke develops suddenly, accompanied by loss of consciousness, seizure or convulsions of the limbs, paresis and paralysis on the side mirroring the affected hemisphere, problems with speech, vision, tongue mobility and swallowing of varying degrees of intensity, mental lability, mood swings, apathy or increased aggression.

Symptoms may occur in reverse order. This does not indicate an erroneous diagnosis, but that the blood clot has “slipped” further, disintegrated into separate fragments, or a hole has formed in it, allowing the blood to continue moving.