Convulsions in a child of the first year of life (infants) are one of the most common pathologies. Suffice it to say that every tenth pediatric emergency call is associated with muscle paroxysms. The baby’s immature central nervous system, the high hydrophilicity of his brain tissue, the weak connection between the membrane and the deep parts - all this creates the prerequisites for a lowering of the threshold of convulsive activity.

In order to accurately determine the root cause of muscle spasms in an infant, a series of diagnostic tests is needed. But a pediatrician and attentive parents, focusing on the nature of the seizures and the accompanying symptoms, will be able to recognize the disease in the child that caused them and provide first aid in a timely manner.

Types of seizures

Based on the nature of muscle spasms, the following involuntary deviations are distinguished: clonic and tonic spasms, minor and myoclonic spasms, spasms during sleep.

Tonic

Characterized by prolonged contraction of all muscles without periods of relaxation. The baby's body is elongated, his head is thrown back, his limbs are frozen in one position. The tonic phase is accompanied by loss of consciousness, respiratory arrest, and cyanosis.

Clonic

Muscle contractions are similar to the movements of a puppet - fast (1-3 contractions per second) rhythmic twitching of any part of the body.

Depending on the number of muscles involved in the pathological process, focal, multifocal and generalized seizures are distinguished.

Neonatal myoclonus

Convulsions during sleep can begin to bother a newborn in the first weeks of life. They usually occur when falling asleep or at the stage of slow-wave sleep. Fingers, wrists, legs, and sometimes facial muscles twitch. Convulsions in infants last in series, 5-6 shudders in a few seconds.

Doctors say that benign myoclonus does not affect the health of newborns and treatment is not required. As you get older, the twitching will become less and less frequent, and by the age of one year it should stop altogether.

But if parents notice such movements in the child while he is awake, then this is already a symptom of pathology, so it is necessary to call a doctor.

Small

Trembling or blinking of the eyes, local twitching of facial muscles, movements similar to chewing, and cyanosis of the skin are observed. A similar condition in newborns may indicate brain injury or neuroinfection.

Myoclonic

These are quite rare in infants. Manifest in the form of bilateral symmetrical contraction of the muscles of the body and limbs. They tend to be serial (the frequency of seizures can reach several hundred per day).

Accompanied by rolling eyes, trembling eyelids, screaming, grimaces. Like small spasms, these types of muscle contractions indicate brain pathology.

Seizures in infants

Home Articles Popular information articles Our children

Of the total number of parental pediatric emergency calls, 10 percent are for seizures. They are especially common in infants. The prevalence of convulsive conditions is 17-20 cases per 1000 population. Professor of the Department of Neurology, Manual and Reflexology, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Chief Children's Neurologist of the city Leonid Aleksandrovich Plekhanov talks about what parents should know about the seriousness of such conditions, their causes, risk factors and their own actions during seizures .

The causes leading to the development of seizures can be very diverse: epilepsy, hormonal disorders, kidney disease, water and electrolyte metabolism disorders, infectious diseases, hereditary pathology, trauma.

Cramps are a sudden involuntary contraction of skeletal muscles, often accompanied by disturbances of consciousness of varying severity. They can be general and local, that is, in a particular muscle group, against the background of clear consciousness and with its loss.

A seizure in most cases is a serious symptom of a disease that affects the brain. Often seizures, especially with loss of consciousness, are the main clinical core of a disease such as epilepsy. Therefore, seizures are usually divided according to their origin into epileptic and non-epileptic.

The frequent development of seizures in childhood is explained both by the characteristics of the child’s nervous system and by the variety of reasons that cause them. Convulsive conditions in infants are determined by the functional immaturity of their nervous system. From a medical point of view, an immature brain is more predisposed to the development of general cerebral reactions than a mature one. The increased “readiness” of the child’s brain for seizure activity can be explained by the relative predominance of excitatory glutamatergic systems over inhibitory glutamatergic systems. That is, in simple terms, in children’s nervous system excitation predominates over inhibition. Imperfect differentiation of the cerebral cortex, its weak regulatory influence on subcortical structures, and significant hydrophilicity of brain tissue explain the child’s tendency to generalized responses (hyperkinesis, agitation, convulsions, etc.) to various stimuli.

According to various authors, from 25 to 84 percent of seizures occur against the background of fever (febrile or hyperpyrexic seizures). A separate group consists of seizures in epilepsy, the prevalence of which is 0.5-1 percent.

Non-epileptic seizures are divided according to the etiological (causal) principle:

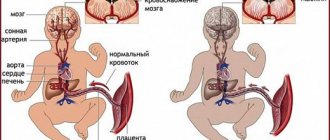

- convulsions due to asphyxia of newborns;

- convulsions during intracranial (birth) and other types of injuries;

- convulsions in hemolytic disease of the newborn;

- convulsions due to congenital defects in the development of the central nervous system, congenital deformities, microcephaly, hydrocephalus and others;

- seizures due to brain tumors;

- convulsions due to pathologies of the vascular system and heart (aneurysm, angiomatosis, acute cerebrovascular accidents, congenital heart defects);

- convulsions in the acute period of infectious diseases (ARVI, influenza, neuroinfections, meningitis, encephalitis, etc.); at high temperatures - febrile convulsions;

- convulsions due to various intoxications;

- convulsions in certain metabolic disorders;

- convulsions in certain blood diseases, etc.

Convulsions in infectious diseases that occur with an increase in temperature in young children are observed more often than in older children, and are the result of an infectious-toxic effect on the child’s brain.

A greater tendency to febrile convulsions is observed in pasty children who have various constitutional anomalies and are prone to generalized reactions (allergies, edema, generalization of infections). When speaking about the convulsive readiness of a child’s brain, I do not mean a brain disease, it is only a predisposition to the appearance of a pathology that may not occur. Therefore, the frequent complaint of parents about changes in the electroencephalogram in the form of “increased convulsive readiness” in a child without previously confirmed epilepsy does not mean anything. I usually recommend checking the EEG study data or not taking it into account due to bias.

Thus, pediatricians and pediatric neurologists have to make a differential diagnosis of febrile seizures in children with symptomatic seizures secondary to infection of the nervous system, or seizures that occur with a rise in temperature in patients with epilepsy. The incidence of febrile seizures ranges from 3 to 8 percent among children under 7 years of age. Risk factors for epilepsy are the complex nature of seizures, neurological abnormalities and the presence of patients with epilepsy among the child’s relatives. Febrile seizures are a combination of genetic and environmental factors. 34 percent of children with febrile seizures had a family history of such seizures, and 4 percent had a relative with epilepsy. Febrile seizures occur most often in children between 6 months and 6 years of age. The average age of onset is 1.5 years; in half of children, febrile seizures are most often noted between 12 and 30 months of life.

Risk factors for recurrence are: onset of attacks before 18 months of age; if seizures occur at temperatures below 38 degrees; when convulsions develop less than an hour after the onset of fever; presence in the family history of indications of febrile seizures. With 4 risk factors, the relapse rate increases to 76 percent. In children who do not have risk factors, the probability of relapse does not exceed 4 percent.

Convulsions in acute neuroinfections (meningitis, encephalitis) occur at the height of the disease and are tonic (tension of the torso) and tonic-clonic (twitching of various muscle groups of the limbs) in nature. Moreover, they more often reflect the syndrome of general brain disorders, occurring with intracranial hypertension and symptoms of cerebral edema. As a rule, convulsions that occur at the height of neuroinfection disappear along with a decrease in temperature.

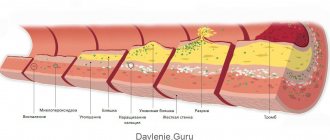

Convulsive conditions can occur with certain metabolic disorders (calcium-phosphorus, amino acid, lipid). In case of disturbances in calcium-phosphorus metabolism (hypocalcemia), convulsions can be caused by symptoms of rickets and a diagnosis of “spasmophilia” is made. A low calcium content is detected in the blood (the norm is 6.0-6.7 percent).

Convulsive manifestations of ricketogenic hypocalcemia are more often observed in late winter and early spring in children aged 6 to 12 months. Convulsions may be accompanied by prolonged spasm of peripheral muscles and transition to general tonic convulsions (general tension of the torso and limbs). Convulsions accompanied by low calcium levels in the blood may have origins other than rickets. During the neonatal period, convulsions can be observed in premature infants due to the significant lability of calcium-phosphorus metabolism.

In rare cases, convulsions caused by hypocalcemia may occur in infants with a sharp and rapid transition to artificial feeding with cow's milk, which contains significant amounts of phosphorus and is not excreted in sufficient quantities in the urine. But these individual facts are not dogma, and parents, based on doctor’s recommendations, can choose natural or artificial feeding without fear.

Epileptic seizures in infants always require accurate diagnosis and correct selection of anticonvulsant drugs. The main method for diagnosing epilepsy is the electroencephalogram (EEG); currently, EEG video monitoring is used to differentiate the epileptic and non-epileptic nature of seizures, as well as to determine various forms of epilepsy. For practical use, let’s use the method of routinely filming an attack on video by the parents themselves; it is clear that sometimes parents have no time for this when this happens to a child, but the real events of what is happening are sometimes indispensable for doctors.

Therapeutic measures for seizures should be aimed at restoring adequate breathing and reducing the excitability of the central nervous system. To ensure patency of the respiratory tract, the child’s mouth and pharynx should be cleared of mucus, food debris or vomit (aspiration using an electric suction or mechanical removal), prevent tongue retraction by lifting the lower jaw at the corners or installing an air vent (if available). The child's head should be turned to the side to prevent aspiration while breathing is restored. You should free the child from tight clothing that makes breathing difficult and provide him with access to fresh air (for example, open a window). These activities are carried out until the arrival of the ambulance team.

Author: Zh. Kiseleva

Based on materials from the newspaper “On Health” (issue No. 11, September 2009)

Print version

Causes of seizures in newborns

Why do convulsions begin in a newborn (infant)? The causes depend on the etiology of muscle spasms. Their appearance is provoked by a viral infection, intoxication, metabolic disorders (hypocalcemia, hypoglycemia, hypomagnesemia), overdose of stimulants, temperature during teething, mental trauma. Progressive lesions of the central nervous system due to trauma or infection of the brain, intracranial hemorrhages are especially dangerous for the baby’s life. Let's look at the most common causes of seizures.

How to deal with cramps

Seizures occur frequently in children, but they cannot be ignored and left without medical supervision. Febrile seizures are involuntary in most cases. This indicates serious problems with well-being. Sick children are placed in a hospital, where they are constantly monitored.

Doctors examine the newborn to determine the cause of the seizures. This will allow you to choose the appropriate therapeutic technique. If the contractions are so strong that breathing stops, hospitals provide airway ventilation.

Drug therapy to eliminate convulsive tremors involves the use of drugs that stabilize metabolism. For this purpose, you need to use magnesium and glucose. Phenobarbital and phenytonin from the barbiturate category are used for therapy.

It is necessary to reduce physical activity and stabilize the functioning of the nervous system. This is done with the help of sedatives like Seduxen.

Regardless of the intensity and duration of seizures in newborns, you should consult a doctor. For mild cramps, you can postpone visiting a specialist. Seizures that last too long require consultation with a doctor.

In order for the baby to have access to air, you need to remove all diapers from him. It is unacceptable to try to stir up a child or give him medication.

Respiratory-affective seizures

They try to exclude this diagnosis first, since in most cases such convulsions do not pose a danger to the baby’s life.

Why does a baby begin to have attacks of respiratory-affective seizures? When a child gets angry or experiences pain (a fall, an injection), he begins to scream loudly. At some point, breathing occurs, the baby’s face turns blue, and he loses consciousness. The nature of muscle spasms is tonic. The attack is accompanied by involuntary urination.

The severity of the problem depends on the duration of the seizure. If convulsions occur suddenly, without reason, last more than a minute and are accompanied by cyanosis of the skin, then the cause may be an abnormality of the trachea, laryngospasm, or foreign body entering the respiratory tract. Call an ambulance - the consequences of such seizures can be very sad (for example, brain damage). The seizure should not last more than 30 minutes.

Hypocalcemia

If in the first months after the birth of a child the concentration of ionized calcium in his blood drops to 1.02...1.37 mmol/l and below, then he develops symptoms of hypocalcemia. It is expressed in hyperexcitability, clonic-tonic convulsions, often painful due to spasm of the laryngeal muscles, muscle hypotension, and vomiting. There may also be loss of consciousness. Then the baby takes a characteristic pose - his arms are bent at the elbows and pressed to the body, and his hands are lowered.

Calcium deficiency has an extremely negative effect on the condition of all body systems. Most often it is diagnosed in premature newborns, twins, children whose mothers have diabetes, and artificial babies.

Hypoglycemia

Low blood glucose levels can also cause seizures in newborns. The lower limit of normal for infants is considered to be 2.2-2.8 mmol/l. Very often, hypoglycemia is combined with hypocalcemia, but the former is much more dangerous, since in its advanced form it can cause coma and pathologies in the development of the nervous system.

Symptoms of low sugar levels are: weakness, tremor, tachycardia, increased heart rate above 130 beats/min, apnea. The resulting convulsions are clonic in nature: they begin with small tremors of the hands, then twitching of the eyeballs and facial muscles is added.

The prognosis is favorable for children whose mothers have diabetes. But if, against the background of low sugar, a child regularly experiences attacks of suffocation, and his emotional background is unstable, then in 35-40% of cases, such children are diagnosed with developmental pathologies at a later age.

Hypocalcemia and hypoglycemia are the most common causes of seizures.

Main causes of violation

According to statistics, every fifth premature baby experiences seizures. In children born on time, the problem is diagnosed with a frequency of up to 10-14 cases per 1000 newborns. Among the main causes of the disorder, pediatricians name the following:

- metabolic disorders due to hypoglycemia or calcium deficiency;

- lack of oxygen flow to the brain;

- infectious damage to the central nervous system with subsequent development of ischemic encephalopathy;

- disruption of the adrenal glands due to their congenital pathology;

- hemolytic jaundice, which is a consequence of high bilirubin in the blood.

Meningoencephalitis

This is the name given to convulsive syndrome caused by meningococcal infection. Occurs against the background of edema and purulent inflammation of the membranes and brain tissue. Edema puts pressure on the motor centers of the cerebral cortex, irritating its nerve cells. As a consequence, excitation processes in neurons lead to uncontrolled muscle contraction.

Symptoms of the disease are: high fever, vomiting, a state of prostration, strabismus, clonic-tonic convulsions (trembling of the chin, movements similar to chewing, twitching of the arms and legs), disturbances in heart rhythm and breathing. An attack may be preceded by screaming, anxiety, fever, vomiting

Seizures due to epilepsy

Such seizures are almost always spontaneous and are not associated with any provoking factor. First, all the muscles of the body tense, followed by a short cessation of breathing, cyanosis, after which rhythmic twitching of the muscles of the arms and legs begins for 1-20 minutes. Sometimes a convulsive spasm looks like a wince with simultaneous separation (compression) of the limbs.

Signs of a seizure

Many parents want to know what symptoms accompany convulsive syndrome, because the baby’s motor activity is so easy to confuse with spasms that accompany many dangerous diseases.

Seizures in children of the first year of life, as a rule, are tonic-clonic in nature and occur in several stages (a few minutes before the onset of a seizure, the child begins to be irritated and capricious).

Tonic phase

Lasts from 20 seconds to 3 minutes. Symptoms are: breath holding and hypoxia, cyanosis, tension of all body muscles (“stiffness”). Babies' eyeballs roll back and their heads fall back. The child loses consciousness. During a seizure, involuntary bowel movements or urination may occur.

Clonic phase

With this type of cramp, individual muscle groups relax for a while and then tense again. These spasms manifest themselves in the form of involuntary stereotypical movements (twitching) with varying amplitudes.

If the spasms begin with the facial muscles, then they sequentially move to the fingers, hands, forearms, shoulders and legs. Breathing is noisy. The slowed pulse during the tonic phase returns to normal, and the complexion gradually returns to normal.

After a seizure, the child becomes unconscious or falls asleep. When he wakes up, he remembers nothing, is irritated and disoriented.

Attention! You need to be especially careful with children who were born prematurely: muscle spasms in premature babies can often be the only sign of cerebral damage.

If the muscles twitch during sleep, then most likely we are dealing with neonatal myoclonus, which was already mentioned above. Having watched the babies while they sleep, we will notice that from time to time they shudder and jerk an arm or leg.

If the number of muscle spasms does not exceed 10-15 at a time, and there are no other symptoms of pathology, then there is no cause for concern. But if the spasms are rhythmic and do not stop, even when you pick up the baby, this is a sign of a disease.

Neonatal seizures

Neonatal seizures According to a widely accepted definition, neonatal seizures (NS) include paroxysmal disturbances in neurological functions (behavioral, motor, autonomic) in a newborn child. This definition does not allow us to distinguish NS from non-epileptic behavioral phenomena that are widespread in the neonatal age. In addition, some children with NS have no clinical manifestations of seizures, while the electroencephalographic correlate is expressed up to electrical status epilepticus. These seizures, without clinical accompaniment, are defined as “latent” seizures or electroencephalographic seizures. It has now been proven that metabolic changes in the brain and the prognosis of children with “latent” seizures correspond to clinically manifested seizures, while the traditional definition of NS leaves this group of children outside its boundaries.

Distribution of neonatal seizures

The frequency of NS varies significantly according to various authors from 0.7-14 per 1000 live births. The wide range in the frequency of NS is determined, on the one hand, by ambiguous criteria for diagnosing NS. In particular, many researchers point to the widespread prevalence of both overdiagnosis of NS and underestimation of their actual frequency. On the other hand, the inclusion (or vice versa exclusion) of high-risk newborns, in particular premature babies, in the study sample also affects the general understanding of the prevalence of NS, since the frequency of NS in newborns from high-risk groups reaches 20-40%.

Clinical picture of neonatal seizures

Seizures in newborns differ in their clinical manifestations from seizures in older children. Among the clinical types of seizures in the neonatal period, fragmentary, atypical clinical paroxysms predominate. An important feature of NS is also the narrow boundaries of the time ranges for the manifestation and relief of seizures. In most cases, seizures begin within the first three days of life. According to a number of researchers, in 81%-95% of children, by the 3rd postnatal day, NS stops and does not recur even if therapy is discontinued. A characteristic feature of the course of NS should also be called frequent and relatively short (on average 2 minutes) attacks. In 33-40% of cases, NS occurs in the form of neonatal seizures.

Thus, the clinical features of NS complicate their diagnosis, the early onset of NS creates the need to provide opportunities for specialized examination of the child in the near future after birth, and the narrow time frame of seizures in the neonatal age significantly reduces the time for carrying out all diagnostic and therapeutic measures.

Classification of neonatal seizures

Classification of neonatal seizures.

According to the J Volpe classification of NS, based on the clinical manifestations of seizures, 4 groups of NS are distinguished:

1. Fragmentary (subtle) seizures

2. Tonic seizures - among them are tonic focal and generalized tonic seizures

3. Clonic seizures - among them focal and multifocal

4. Myoclonic focal, multifocal and generalized seizures.

Treatment of neonatal seizures

First of all, NS therapy is aimed at treating the underlying disease and maintaining optimal respiratory parameters, glucose-electrolyte composition of the blood, and thermal conditions. Carrying out pyridoxine and calcium tests is considered mandatory.

When prescribing antiepileptic drugs, it is necessary to keep in mind the possible negative consequences on the somatic status and neuropsychic development of the child. The drug of first choice in neonatal practice is still phenobarbital at a dosage of up to 40 mg per kg. Studies conducted in recent years show that the administration of phenobarbital at a loading dose of 20 and even 40 mg/kg leads to the elimination of only the clinical component of seizures, and does not affect the frequency and duration of “electroencephalographic seizures” (only in 29%-20% children were eliminated and “electrographic seizures”). Thus, as a result of treatment with phenobarbital, electroclinical uncoupling is formed. As a result, phenobarbital is currently losing its position as the optimal drug for the treatment of NS. Phenytoin at a loading dose of 20 mg/kg and a maintenance dose of 5-8 mg/kg, according to research data, is similar in effectiveness to phenobarbital. Among benzodiazepines, lorazepam is used at a dose of 0.05 - 0.1 mg/kg and clonazepam at a dose of 100-200 mg/kg and then 20-30 mg/kg/hour if seizures persist. All of these drugs have a wide range of side effects, including slowing of neuropsychic development, behavioral disturbances, and their ability to influence the “electrical” component of seizures has not been proven using prolonged EEG monitoring. Moreover, a comparison of the follow-up of children with NS treated with traditional drugs and those who did not receive anticonvulsant therapy not only showed the low effectiveness of traditional treatment regimens, but also did not reveal differences in prognosis. Thus, at the moment there are no well-tested, effective methods for treating NS, and the issue of developing a strategy for the management of newborns with seizures is urgent.

Attempts to use it for the treatment of NS are of interest. more modern antiepileptic drugs. Valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine have been used in isolated cases for resistant seizures. In particular, the results of the use of valproate are encouraging, their effectiveness was 83% among children with prolonged seizures resistant to phenobarbital at a dosage of 40 mg per kg. There are isolated reports of the use of valproate in the treatment of neonatal seizures in rectal, intravenous and oral forms.

It should be noted that intravenous forms of anticonvulsants are predominantly used for the treatment of NS. Considering the peculiarities of the course of NS (high frequency during the day, early manifestation and resolution up to 3 days of life in many newborns), theoretical justification for prescribing oral forms of drugs is insufficient. Due to the long absorption time of a number of antiepileptic drugs (phenobarbital, carbamazepines), the time to create a stable concentration of the anticonvulsant may be comparable to the time of spontaneous resolution of seizures. In many newborns, especially those with multisystem hypoxic, infectious or metabolic damage, the ability to absorb from the gastrointestinal tract is also reduced. However, in domestic practice, oral forms of anticonvulsants are used, due to the unavailability of a number of intravenous forms (intravenous phenobarbital, intravenous phenytoin), despite the fact that there are studies that could confirm the effectiveness of oral forms of antiepileptic drugs for relieving clinical and electroencephalographic equivalents of NS was not carried out. Duration of therapy, taking into account the multiple side effects of anticonvulsant therapy, the relatively low risk of recurrence of seizures during the first year of life (8-20%) and the absence of its increase with early withdrawal of anticonvulsants, long-term anticonvulsant therapy in children who have had NS is not recommended. At the same time, the issue of the exact timing and schedule of discontinuation of antiepileptic drugs in newborns continues to be discussed.

Diagnostics

Determining the root cause of seizures is possible only after a series of studies. Immediately after the attack, the pediatrician begins to collect anamnesis. It evaluates parameters such as temperature, pressure, airway patency. The details of the attack and hereditary burden are considered. If necessary, the child is hospitalized, tests are prescribed for glucose, calcium, magnesium, chlorine, and toxicological studies are carried out. If the doctor suspects a brain pathology, the baby is sent for CT, EEG, and neurosonography.

First aid and treatment

When a baby loses consciousness and begins to convulse, it is scary. The main thing is not to panic in such a situation and provide the child with timely first aid.

First aid for seizures

During a child's seizure activity, parents should not:

- shake and hold the child close (parents in a state of passion may not calculate their strength and cause injury to the baby);

- leave the child in a supine position;

- open the jaws with hard objects, try to give the baby something to drink or give him medicine;

- perform artificial respiration or chest compressions if respiratory and cardiac activity is present.

First of all you need:

- call an ambulance;

- ensure free breathing by placing the child on his side, undress him and cover him with a sheet (if necessary, clear the mouth and throat of mucus and vomit);

- during an attack, record the frequency and duration of the attack; If possible, videotape the seizures (this will help the doctor make a diagnosis).

Helping your child with seizures

The occurrence of seizures is a very dramatic moment for parents; here you need to know what to do:

- Remain calm and do not leave observation of the child for a second;

- Place the baby on his side on a soft surface, making sure that there are no objects nearby that he could hit or injure himself on;

- Provide air flow;

- If the convulsions were associated with temperature, after the end of the attack, administer an antipyretic drug rectally; in addition, wiping with water can be used. Rubbing should not be used if the convulsions continue for a long time, the child turns pale, and his lips turn blue.

Wiping with water at a temperature

Important! During an attack, it is forbidden to give the baby any pills, food, or drink.

If seizures occur for the first time, the child must be examined by a doctor. When convulsions do not stop for more than 5 minutes or are repeated, and the baby loses consciousness, you need to call emergency services.

Treatment

The occurrence of seizures should not be ignored, especially in children of the first year of life. The fact is that the body of infants is prone to generalization of any process, so therapy and examination of the child must be carried out in a hospital setting. Based on a preliminary diagnosis, the child is hospitalized in a neurological or infectious diseases department. Treatment depends on the diagnosis made after diagnosis.

Febrile seizures

The baby is given an antipyretic - the first choice drugs. Drugs from the benzodiazepine group are used as anticonvulsants. These are the features of the treatment of seizures. The prognosis is generally favorable, and seizures with complications occur in only 1% of cases. There is a nuance: the smaller the child is at the time of his first febrile convulsions, the more likely (up to 30%) they will be repeated during the next hyperthermia.

Respiratory-affective seizures

If the baby has not lost consciousness and is in a state of hysterics, then convulsions are one of the ways he tries to achieve what he wants (toys, for example). Try to redirect his attention. Sometimes it is possible to stop a seizure by simply patting the child on the sides, blowing in the face, or splashing cold water on him.

Hypocalcemia

The child is given an intravenous solution of calcium in glucose, and for persistent convulsions - intravenous magnesium sulfate.

Hypoglycemia

IV administration of dextrose and glucose solutions until the seizures stop. The next day, the glucose infusion is continued, gradually reducing the dosage. It is impossible to stop abruptly, as this will provoke reactive hypoglycemia and return seizures.

Meningoencephalitis

This disease is treated only in a hospital setting. Comprehensive therapy: antibiotics, anticonvulsants, neuroprotectors, a diuretic to relieve cerebral edema, angioprotectors.

Seizures due to epilepsy

Curing epilepsy is a long process, but with properly selected drug therapy, 30% of children recover completely, and the rest manage to reduce the duration and frequency of attacks. As a rule, anticonvulsants are prescribed, the choice of which depends on the type of epilepsy (idiopathic, symptomatic, cryptogenic).

Modern approach to understanding and treating neonatal seizures

The article presents the results of a study of 85 patients with neonatal seizures (NS). The issues of pathogenesis and treatment of these conditions are discussed, the importance of modern instrumental examination methods and the most common long-term consequences of NS are shown.

Modern approach to the understanding and treatment of neonatal seizures

Article conducted the results of the survey 85 patients with neonatal seizures (NS). Discussed questions the pathogenesis and treatment of these conditions, the importance of modern instrumental methods of examination and the most frequent long-term consequences of NA.

Despite the fact that neonatal seizures (NS) are the result of many causes, the main ones, according to most researchers, are ischemic-hypoxic encephalopathy, intracranial hemorrhage, infections and congenital malformations. All of the listed diagnoses are very general and do not meet the requirements of the modern classification of perinatal lesions of the nervous system [8]. Despite the fact that neonatal seizures are reliably considered a sign of severe neurological damage to the brain, they have generated much scientific debate about their pathogenesis. For example, is NS a consequence of brain damage or do what are called seizures damage the brain? Unfortunately, the risk factors for NS have not yet been sufficiently studied. Neonatal seizures are common and may be the first manifestation of neurological dysfunction after various injuries. Seizures in newborns are clinically significant primarily because very few of them are idiopathic. Further studies leading to timely diagnosis of the underlying condition are important because early initiation may improve prognosis.

Neonatal seizures lead to nonphysiological apoptosis, but it is not clear whether this leads to further clinically significant neuronal damage in all types of seizures, or whether negative consequences can be prevented with the help of therapy. Therefore, many clinicians are uncertain when treatment for seizures is required and how to assess the adequacy of treatment.

An immature brain seems more prone to seizures; they are more common during the newborn period than at any other time during life. This may indicate an earlier development of excitatory synapses that predominate over inhibitory influences at the early stages of maturation. The prevalence of clinical seizures in infants born at term is 0.7-2.7 per 1000 live births. The incidence is higher in premature infants, ranging from 57.5 to 132 per 1000 live births (birth weight <1500 g).

In 75% of patients, epilepsy debuts in childhood. Thus, in the future, in most cases, neurologists observe the evolution of epilepsy. Therefore, the most important thing is the time of onset of epilepsy, its adequate therapy with the main goal of avoiding the transformation of one epileptic seizure into another, achieving their maximum control.

Neonatal seizures are reliably recognized as one of the main neurological syndromes of children in the first 4 weeks of life. Today, this is one of the most controversial problems in neuroscience, starting with its definition. If we consider that NS is a generalized reaction of the newborn’s nervous system to various neurological, somatic, endocrine and metabolic disorders [9], then we can treat them as a transient symptom that does not require therapy, which is very widely represented in neonatology. Many other definitions of neonatal seizures are known. Unfortunately, none of them requires either a search for causes or research into the consequences of NS. We prefer the point of view of the majority of neurologists, who consider NS to be the first reliable sign of severe brain damage in a newborn, with the exception of idiopathic seizures, which are much less common [2, 3, 6]. A large scatter in statistics most often indicates its imperfection for many objective reasons. The minimum frequency of NS is most typical for underdeveloped countries, where NS often goes unnoticed by neonatologists or parents of newborns, and diagnostic methods are imperfect [4]. It is very important for clinicians and little known that latent seizures are more typical for newborns, they are also called electrographic seizures. Most electrical seizures are not accompanied by clinical correlates. At the same time, not all clinical seizures correlate with EEG changes. Neonatal seizures differ in clinical description from seizures in adults, and seizures in premature infants differ from seizures in children born at term. The organization of the cerebral cortex, synaptogenesis and myelination of efferent neurons are poorly developed in newborns, which rarely leads to bisynchronous propagation of excitation. Therefore, fragmented seizures are more typical in newborns, and electrical activity may not spread to the surface of the EEG electrodes. Only with the help of such a research method as video-EEG monitoring is it possible to differentially diagnose various types of apnea [2]. The phenomenon of electroclinical disconnection is most often determined in newborns with fragmented seizures, generalized tonic and focal myoclonic paroxysms, which may not be accompanied by simultaneous EEG correlates.

An analysis of the literature of recent decades shows that the majority of authors both in Russia and abroad are inclined to hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in the perinatal period as the main cause of NS [7, 8]. JM Rennie (1997) believes that seizures are a general response of the brain to a stroke [5]. D. Evans, M. Levene (1998) pay special attention to the significance of moderate and severe hypoxia-ischemia, when NS appears in the first 24 hours of a child’s life and has an unfavorable prognosis [2]. And H. Tekgul, K. Gauvreau and co-authors (2006), having conducted a study of 89 children with NS, indicate that in 82% of cases, global cerebral hypoxia-ischemia was detected in newborns of this group, which led to death in 7% of children and in 28% to severe neurological changes at the age of 12-18 months [6]. The term hypoxic-ischemic brain damage, generally accepted in the literature, is sometimes replaced by the outdated concept of “hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.” One way or another, the criteria for this most common and life-threatening condition in perinatology have not yet been determined. This is a set of indicators, which include the Apgar score not only at birth, but also after 5 minutes, the severity of acidosis, the need for mechanical ventilation, convulsions and others. The causes of NS are many pathological processes of the mother and child, including metabolic disorders, congenital cortical malformations, infections, of which bacterial meningitis is the most common.

The relevance of the study of neonatal seizures is determined not only by their insufficient knowledge, but also, to a greater extent, by their severe neurological consequences, which include motor disorders, cognitive deficits, social maladaptation and the formation of late epilepsy. Many scientific studies are devoted to the search for risk factors for the development of NS, which could help improve the algorithm for managing a patient with NS depending on the cause of its occurrence, neurological symptoms in the first hours of life, indicators of the energy balance of the newborn’s body and instrumental research methods [1, 3, 6, 7 ].

Taking into account the symptomatic nature of most neonatal seizures, we set ourselves the main task of determining the proportion of perinatal brain pathology and, in particular, intranatal pathology in the development of nervous system. We believe that it is no less important to evaluate modern approaches to the monitoring and treatment of patients with NS in practical healthcare. We consider one of the tasks to be the creation of an algorithm for the management of a newborn with NS.

Materials and methods . The study included 85 children aged 1 month to 17 years who had neonatal seizures. The exception was newborns with idiopathic NS. A thorough assessment of obstetric and early postnatal history was combined with a neurological examination of the child. Patients aged from 1 month. up to 1 year there were 33 (1st group), from 1 year to 5 years - 40 (2nd group) and from 5 years to 17 years - 12 (3rd group).

In the 1st age group, in the first days of life, 76% of patients, in addition to NS, had grade II-III cerebral ischemia verified, and in 24% of newborns it was combined with intraventricular hemorrhages and in 18% with CNS depression syndrome. It is customary to talk about the neurological consequences of perinatal brain pathology by the age of 12-18 months. By 1 year of life, 52% of patients with NS were diagnosed with epilepsy and 71% developed a persistent neurological deficit. In all infants, according to the results of ultrasound examination, blood flow disturbances were combined with signs of hypoxia. The undisputed generally accepted algorithm for examining newborns with NS in the world is neuroimaging (MRI and CT). None of the newborns from the first group of children we examined underwent neuroimaging in the first month of life. In 29% of the examined children with recurrent epileptic seizures, according to MRI and CT, gross changes were revealed - by the age of 1 year, the picture of internal ventricular hydrocephalus and cystic-atrophic changes in the cerebral hemispheres prevailed. NSG, as the most accessible diagnostic method, was performed in 60% of patients with NS. In 9 examined children, periventricular cysts predominated, in 4 - intraventricular hemorrhages, and in another 5 - signs of intraventricular hydrocephalus. Ophthalmoscopy data performed on 65% of patients showed partial atrophy of the optic nerves in 30%, and retinal angiopathy of varying severity in 70%.

When analyzing the anamnesis data of patients of the 2nd age group (1 year - 5 years), we did not note any large statistical differences in the symptoms of the first days of life. Subsequently, 60% of children developed cerebral palsy, in 22% of patients it was combined with symptomatic focal epilepsy and in 18% with symptomatic West syndrome. That is, by the age of 5, more than a third (40%) of children who suffered from NS suffered from epilepsy. According to MRI data performed on 13 children out of 40, mixed ventricular hydrocephalus was found in 13%, cystic atrophic changes were found in 10%, and anomaly of brain development was noted in 7%, in particular, hypoplasia of the corpus callosum. According to the results of ultrasound scanning, in 30% of patients asymmetry of blood flow in the vertebral arteries predominated, and in 20% of them it was combined with severe venous dystonia, in 7% of patients signs of hypoxia were described.

All 12 patients of group 3 (5-17 years old) had grade II-III cerebral ischemia during the neonatal period; The 100% rate of ischemic disorders in this group, in our opinion, has no objective reasons, but once again allows us to note the high frequency of hypoxia-ischemia in newborns with NS. The degree of ischemia predominated in very preterm infants, as did the frequency of neurological consequences. The data from the neurological examination and instrumental research methods did not differ from the two previous groups, which allowed us to conclude that neurological outcomes were developing by the age of 12-18 months in children with NS. We consider the significant difference between the 3rd age group and the first two to be the frequency of headaches (73%) and cognitive impairment in the form of decreased memory, perception, and concentration in 62% of patients tested by a psychologist. It is in this group of patients that one can reliably judge the long-term consequences of neonatal seizures. And the most common late complications turned out to be cephalgia, essentially perinatally caused, and attention deficit disorder.

The diagnosis of epilepsy today requires mandatory EEG monitoring, that is, continued EEG recording. Unfortunately, we found that even routine EEG is not performed on all patients with NS, either in the first days of life or during the first year. The reason for this study was the onset of seizures, which required differentiation from epileptic ones. Continuous EEG is recommended for children with perinatal pathology of the central nervous system and nervous system, in order not to miss seizures in the event of their visual absence, to determine the frequency and duration of seizures. Unfortunately, access to EEG monitoring is limited in most clinics, and interpretation largely depends on the EEG performer, requiring considerable experience. Detection of interictal abnormalities in background EEG is useful in determining prognosis in both term and preterm neonates. The worst prognosis is associated with a burst-suppression pattern and persistence of persistent low-amplitude waves.

33 patients with NS aged from 3 months. up to 17 years of age, video-EEG monitoring was performed in a hospital setting. When monitoring wakefulness in a background recording, organic changes were recorded on the EEG in 60.6% of cases (20 people). The vast majority - 72.7% of patients (24 people) showed epileptiform activity during the study. In 15.2% (5 people) hospitalized in the department of infants and young children with damage to the central nervous system and mental disorders with a diagnosis of symptomatic West syndrome, electroencephalographic changes characteristic of various variants of modified hypsarrhythmia were noted.

In symptomatic focal and multifocal epilepsy, regional and multiregional epileptiform changes were recorded in 51.5% (17 people) of cases, in 3% of cases (1 person) complexes reminiscent of benign epileptiform patterns of childhood were noted. In one child, suppression of cortical rhythms was recorded on the EEG.

In 21 patients, video-EEG monitoring was performed after receiving the results of routine EEG. During the initial routine EEG, epileptiform disorders were detected in 23.8% of children with a history of neonatal seizures. Video-EEG monitoring of wakefulness and sleep revealed epileptiform activity in 85.7% of cases, and in 61.9% of cases epileptiform activity was detected for the first time only during an EEG monitoring examination, that is, a routine EEG method using a standard technique for recording bioelectrical activity of the brain did not reveal epileptiform disorders. Isolated, only in a state of sleep, epileptiform activity was detected in 28.6% of cases, which increases the significance of conducting EEG monitoring studies in this physiological state.

The main goal in the treatment of neonatal seizures is to relieve the symptoms of the underlying disease and maintain optimal respiratory parameters, blood glucose-electrolyte composition and thermal conditions. The biggest debate is the question: to treat or not to treat NS? Prolonged or poorly controlled neonatal seizures are associated with a worse outcome than infrequent or easily controlled seizures, but the severity of the underlying disorder may lead to poor seizure control and poor outcome. There are no clinical data to show that anticonvulsant treatment changes neurological outcome when controlling underlying neurological impairment. Many of the most commonly used AED regimens are ineffective in controlling all seizures, clinical or electrical. Abnormal EEG activity persists in a significant proportion of neonates who show a clinically positive response to AEDs.

It may be necessary to attempt to control frequent or prolonged attacks, especially if homeostasis, ventilation, and blood pressure are compromised. It is considered necessary to prescribe AEDs if there are three attacks per hour or more, or if one attack lasts 3 minutes or more. After clinical seizure control, persistent EEG seizures are rarely treated because they tend to be brief and fragmented—further increasing dosages increase the risk of side effects. Many anticonvulsants depress respiration and impair myocardial function. The duration of therapy also causes considerable debate, but when seizures are controlled for a week and the neurological status is normal, AEDs are usually discontinued.

The drug of first choice in neonatal practice is still phenobarbital (PB) at a dose of 20-40 mg/kg/day in 2 doses. At the same time, recent studies show that FB suppresses only the clinical component of seizures and does not affect the frequency and duration of “electrical attacks”, that is, the phenomenon of electroclinical disconnection is formed. The second-line drug of choice is diphenin at a dose of 10-20 mg/kg/day. Studies in recent years show a good effect of valproate at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day. Data have emerged on the positive effects of topiramate in neonatal practice. To date, no reliable comparative data have been obtained on the benefits of a specific AED in the treatment of NS.

conclusions

1. Neonatal seizures in most cases are a consequence of perinatal damage to the newborn’s brain, and most often hypoxia-ischemia.

2. Most of the nervous system is not visualized and manifests itself only as hidden, “electrical” attacks.

3. To date, there is no algorithm for the management of patients with NS. EEG monitoring and neuroimaging are performed extremely rarely in the first days and months of a child’s life.

4. Treatment of NS is debated, but requires first of all eliminating the cause of the development of NS, starting from the first minutes of life.

5. The consequences of NS are persistent neurological deficits, cognitive impairment, and epilepsy.

E.A. Morozova

Kazan State Medical Academy

Morozova Elena Aleksandrovna - Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Child Neurology

Literature:

1. Arpino C. Prenatal and perinatal predictors of neonatal seizures in the first week of life C. Arpino, S. Domizio // Journal of Child Neurology. - 2001. - No. 9. - R. 17-23.

2. Evans D. Neonatal seizures / D. Evans, M. Levene // Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. - 1998. - No. 78. - R. 70-75.

3. Murrey DM Prediction of seizures in asphyxiated neonates: correlation with continuous video-electroencephalographic monitoring / DM Murray, CA Ryan, CB Boylan // Pediatrics. - 2006. - No. 1. - R. 1140-1151.

4. Mwaniki M. Neonatal seizures in a rural Kenyan District Hospital: aetiology, Incidence and outcome of hospitalization / Mwaniki, A. Mathenge, S. Gwer1 // Medicine. - 2010. - No. 8. - R. 8-16.

5. Rennie JM Neonatal seizures / JM Rennie // Eur. J Pediatr. - 1997. - No. 156. - R. 83-87.

6. Tekgul H. The Current Etiologic Profile and Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Seizures in Term Newborn Infants / H. Tekgul, K. Gauvreau, J. Soul // Pediatrics.-2006. - No. 6. - R. 1270-1280.

7. Zelnik N. Predictors of epilepsy in neonates with cerebral injury / N. Zelnik, M. Konopnicki, T. Castel-Deutsch // Paediatr Neurol. - 2010. - No. 14. - R. 67-72.

8. Guzeva V.I. Epilepsy and non-epileptic paroxysmal conditions in children / V.I. Guzev. - M., 2007. - 568 p.

9. Epileptology in medicine of the XXI century / A.A. Kholin, E.S. Ilyina, K.V. Voronkova, A.S. Petrukhin / ed. E.I. Guseva, A.B. Hecht. - M., 2009. - 572 p.

Prevention

How to keep a child prone to seizures healthy? Your actions are:

- after the first attack, parents must register their child with a neurologist;

- gymnastics for infants, massage sessions, adherence to a daily routine and daily walks will strengthen the immune system and

- reduce the risk of a recurrent attack;

- there is no need to overload the child’s nervous system (calm mother, calm baby).

The convulsive reaction of the baby’s body frightens parents very much, but it is precisely this sign of pathology that cannot be ignored. Modern diagnostics make it possible to find out the root cause at the earliest stages of the disease, so the main task of mom and dad is to be vigilant and seek medical help in a timely manner.